Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Wednesday, 5 December 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Ashani Abayasekara

One in eight people worldwide experiences some form of disability. Children with disabilities are often excluded from educational opportunities, and are overlooked when it comes to school completion and learning outcomes. Evidence from 19 developing countries points to a worrying trend of increasing gaps in school completion rates and literacy skills, between children with and without disabilities.

The globally-embraced, 2030 agenda for Sustainable Development reiterates the importance of ensuring that children with disabilities have the same opportunities for learning as other children, particularly in its inherent principle of “leaving no one behind”.

As a signatory to many international conventions on protecting the rights of persons with disabilities and the introduction of its own National Policy on Disability in 2003, Sri Lanka has a well-established disability-specific legislation, covering many areas.

With respect to education, several circulars have been developed focusing on special access facilities for special needs students and teacher appointments, training, and incentive payments. However, there is a lack of comprehensive data to examine the actual circumstances of persons with disabilities, while there is also little analysis done based on available data.

This blog takes a look at existing data on education for children with disabilities in Sri Lanka and highlights some key areas that require policy attention.

Low educational engagement at higher education levels

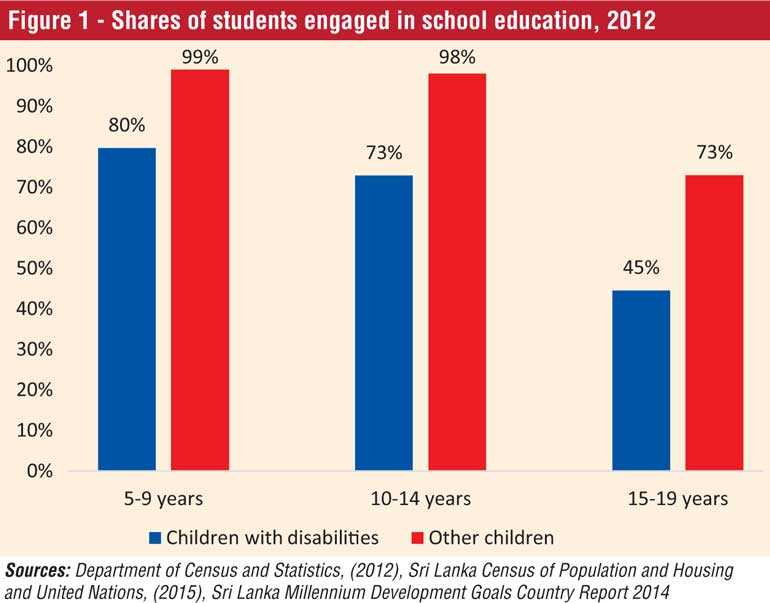

Sri Lanka’s latest Population Census of 2012 indicates that around 2% of children between the ages 5-14 have some form of disability, of which around only three-fourths attend school, compared to the near universal enrolment of other children.

In addition, this share falls considerably with age; as shown in Figure 1, the share of total disabled students engaged in educational activities ranges from a high of 80% among 5-9-year-olds who attend primary school, to only 45% among 15-19-year-olds, including students at the upper secondary (grades 10 and 11) and collegiate (grades 12 and 13) levels.

While school attendance shares also decline with age for other children, the drops are less pronounced. The largest gap between school engagement of children with disabilities and others is at the upper secondary and collegiate level.

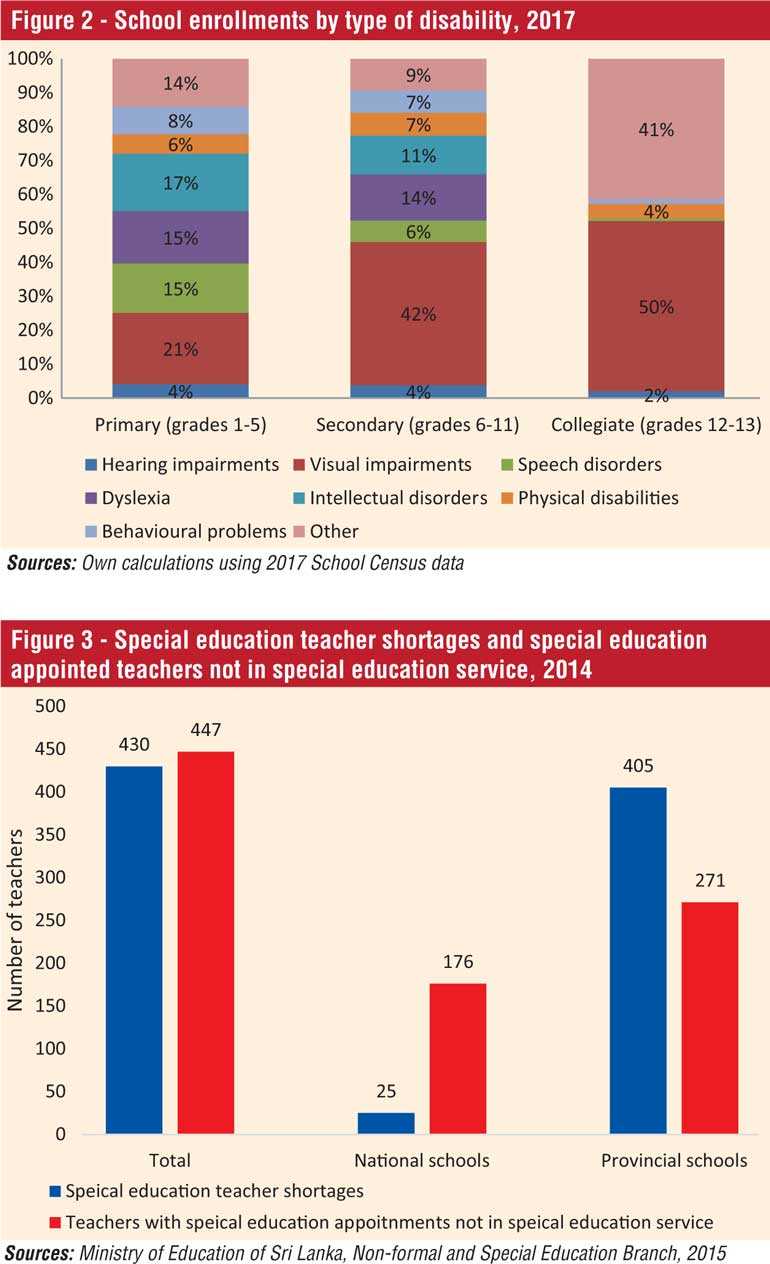

Unbalanced composition at the collegiate level

Figure 2 indicates that the collegiate level is also marked by a skewed composition in enrolments by type of disability, compared to a more balanced distribution at the primary and secondary levels. The share of students with visual impairments increases with the level of education, and make up half of collegiate student enrolments.

Students with other types of disabilities, however, account for negligible shares at the collegiate level. This observation could be partly attributed to the relatively large population of persons with visual impairments in the country. It is also understandable that students with intellectual disorders would find it hard to continue at higher levels of education.

Nevertheless, the large drops at higher grades in other types of disabilities, such as speech, physical, and hearing difficulties, is concerning. Interviews with education sector officials suggest that the lack of supportive infrastructure to accommodate their specific needs, including classroom facilities and learning resources, is a key contributory factor.

For instance, many schools and universities have well-developed Braille learning facilities and specially-designed examination papers for subjects like science and mathematics, with the exclusion of graphs and figures, for visually impaired students. However, similar facilities for other disability types, such as sign language interpreters for students with hearing problems, are scarce.

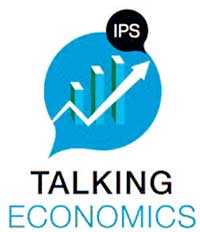

Shortage of special education teachers

The shortage of special education teachers (Figure 3) is another potential reason causing children with disabilities to leave school early. This is in contrast to an excess of regular teachers at the national level, as noted in a recent IPS study.

Even more concerning is that a fair number of teachers appointed for special education are not actually engaged in special education. In national schools, for instance, those who have been absorbed into special education teacher service, but who are no longer in service, is seven times the number of the recorded special education teacher shortages. As reflected in the total numbers, had appointed teachers been actually engaged in special education, there would be no special education teacher deficit at the national level.

While more research is needed to uncover the reasons behind this trend, preliminary interviews suggest that a combination of factors, including the challenging nature of the job, particularly in the context of poor infrastructure facilities, social stigma attached to special education, and the higher status accorded to regular education teachers, induce many teachers to switch from special education to regular education after serving in the former for a few years.

Making education more disability-inclusive

Despite Sri Lanka’s well-established legislation promoting disability-inclusive education, the above analysis suggests that there are large gaps between policy and practice. Using existing data to advocate for implementing identified policy priorities, in line with existing legislation, is important in moving forward.

For instance, the observed positive association between facilities available for the visually impaired and their enrolments at the collegiate level provides a strong basis to advocate for more assistive facilities for other types of disabilities, such has hearing, speaking, and physical impairments. Similarly, the high tendency of teachers to abandon their special education appointments calls for strict monitoring of teacher movements.

In fact, recognising this problem, the Ministry of Education issued a recent circular stipulating strict disciplinary action and withdrawal of a 10% bonus of the basic salary for special education teachers vacating their respective postings. Such monitoring should also take into account teacher training and appointments by type of disability, to ensure that children with all types of disabilities have access to competent teachers.

[Ashani Abayasekara is a Research Officer at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To talk to the author, email [email protected]. To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking

Economics’ – http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/.]