Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Friday, 24 April 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Ramya Kumar

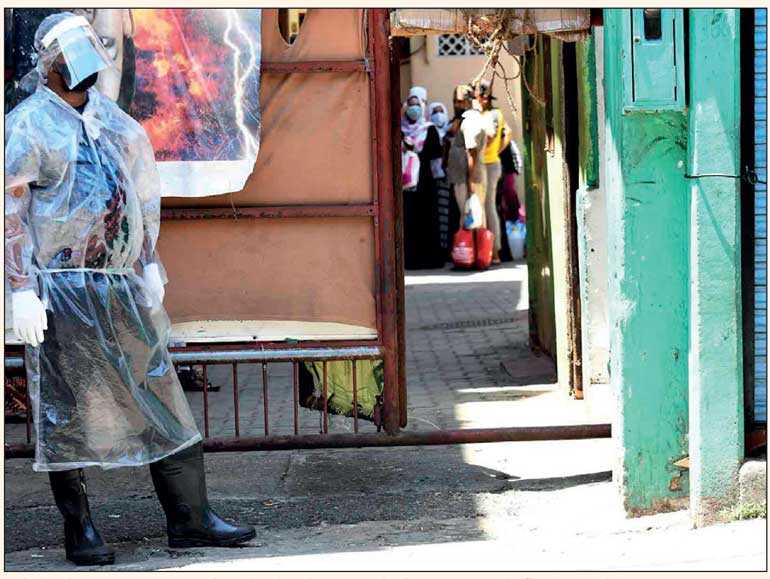

In responding to epidemics, states are compelled to resort to restrictive measures to contain the spread of infection, including quarantine and isolation procedures, travel bans, lockdowns, and curfews. With such restrictions on movement, draconian measures are often swiftly implemented as a subdued citizenry remains compliant, in support of national efforts to combat an unknown ‘enemy.’ In Sri Lanka, we are seeing strict censorship alongside the fast and furious implementation of policies and measures that would otherwise have faced widespread protest and dissension.

Restrictions on free speech are detrimental to public health efforts. Dr. Li Wenliang, the whistleblower who succumbed to coronavirus in February, is now deemed a martyr in China for having alerted colleagues about the novel coronavirus through social media. Instead of responding appropriately to contain the spread of the virus, Chinese authorities interrogated the doctor on the grounds of spreading fake news and silenced him, in effect, delaying its response to the epidemic. Similarly, a number of healthcare workers in the United States have been fired after speaking out about their risky work conditions.

In Sri Lanka, there seems to be substantial self-censorship within the Ministry of Health’s COVID-19 control program. Apart from the numbers reported by the Epidemiology Unit, we do not know on what basis decisions are being made to quarantine communities, or to extend (and lift) curfews. We do not know who is involved in making these decisions. There are concerns that the military is overriding the Ministry of Health’s authority in such matters. This lack of information is enabling the spread of wild rumours, including allegations of falsified COVID-19 statistics. In this context, it may be useful to consider the World Health Organization’s recommendation for a national COVID-19 risk communication strategy:

“Proactively communicate and promote a two-way dialogue with communities, the public and other stakeholders in order to understand risk perceptions, behaviours and existing barriers, specific needs, knowledge gaps and provide the identified communities/groups with accurate information tailored to their circumstances. People have the right to be informed about and understand the health risks that they and their loved ones face. They also have the right to actively participate in the response process. Dialogue must be established with affected populations from the beginning. Make sure that this happens through diverse channels, at all levels and throughout the response.”

Has there been two-way dialogue? Have communities been involved in this process? Unfortunately, no. Furthermore, there has been very little critical analysis of the COVID-19 response in Sri Lanka. We only hear of the glowing and well-deserved tributes to frontline healthcare workers and others involved in control efforts. There has been little engagement with communities affected by the crisis. In fact, we do not even have the space to question our pandemic control strategy—now a matter of national pride.

Last week in Jaffna, we heard that 12 new cases of COVID-19 had been detected at quarantine centres. As Dr. Murali Vallipuranathan, Consultant Community Physician, reasonably opined, these cases may have been new cases that emerged after an extended incubation period or the result of cross-infection at quarantine centres.

When Dr. Vallipuranathan posted his comments on social media, the authorities could either have responded with facts to counter his theory, or, alternatively, taken speedy action to investigate and remedy the situation. Instead, Dr. Vallipuranathan was vilified for questioning the COVID-19 control program. In a letter dated 17 April, the Government Medical Officers’ Association (GMOA), which is supposed to be a trade union fighting for the rights of doctors, complained to the Director General of Health Services that Dr. Vallipuranathan “who has a controversial and racist previous history” expressed “views detrimental to the Health Department and Sri Lanka Army”.

To make matters worse, earlier in April, the IGP instructed the Police to take strict action against those who criticise Government officials engaged in COVID-19 control. A number of arrests were subsequently reported in the media over the spread of so-called fake news. While the details of these seemingly arbitrary arrests are not known, we should be very concerned when even a mere questioning of the country’s COVID-19 control strategy is viewed to be unpatriotic. While dissent is nipped in the bud instantly, hate speech flows with impunity. Just a year after the Easter bombings, the highly organised anti-Muslim discourse-generating machine is once again propagating a familiar tale in which Muslim communities are constructed as the ‘enemy’. We are being told that Muslims are conspiring to transmit infection; they deserve en masse quarantine in (unsafe?) centres; and that it is acceptable to enforce cremation in lieu of burial. Even the medical profession is complicit here as evidenced in an earlier version of the GMOA’s proposals for a COVID-19 exit strategy, which shockingly included the size of the Muslim population in a DS division as a variable for risk stratification.

Earlier in April, the Ministry of Health helpfully issued guidelines for media reporting, stipulating that personal details of patients with COVID-19, including their ethnicity, should not be reported. They called for reporting that builds solidarity in this time of crisis. In this context, the adoption of compulsory cremation as Government policy—contrary to WHO guidelines—seems to demonstrate a double standard, particularly when we see mass burials taking place in other countries ravaged by the pandemic.

Moreover, the Ministry of Health has failed to issue statements to counter insinuations made by the media, as well as some political leaders, that have served to stigmatise Muslim communities as disease-laden, insular groups who are unwilling to follow public health measures. It is hardly surprising then that sections of these communities may be wary of interacting with the public healthcare system.

Even as dissent is repressed, and hate speech is nurtured, the Government is acting fast, facing little or no resistance. We saw the appointment of numerous military officials to key positions in the pandemic control program that should rightfully be occupied by civil administrative officials. Such militarisation has resulted in an autocratic style of governance with very little information sharing. For instance, we have not been informed on what basis the decision was made to partially lift the curfew on 20 April. Neither do we know who was involved in the decision-making process. It is hardly surprising then that many have arrived at the conclusion that Parliamentary Elections are being prioritised over public health.

This style of governance is also seeping into our institutions. As university teachers, we have received orders from the University Grants Commission (UGC) to commence online teaching as soon as possible. With no discussion of the merits of online teaching or the urgency for its implementation, we are adopting new pedagogical methods via Zoom and/or Moodle. Meanwhile, students—including those from farming families experiencing dire financial difficulties in the Vanni and other areas (where network coverage may be weak)—are expected to engage in learning activities through their smart phones—‘everyone has a smartphone’. The lack of foresight in decision-making is mindboggling, as is our silence.

With the curfew being partially lifted, this is a call to critically engage with the measures that are being swiftly implemented at this time of crisis. Let’s demand that the citizenry be involved in processes of decision-making at all levels. Let’s insist that public sector officials with the relevant expertise and experience are placed at the helm of this national pandemic control effort. And, finally, let’s condemn the ongoing anti-Muslim attacks and resist ethno-chauvinist mobilisations in the run up to the elections.

(The writer is attached to the Department of Community and Family Medicine, University of Jaffna, and is a member of the Public Health Writers’ Collective)