Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday, 28 February 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

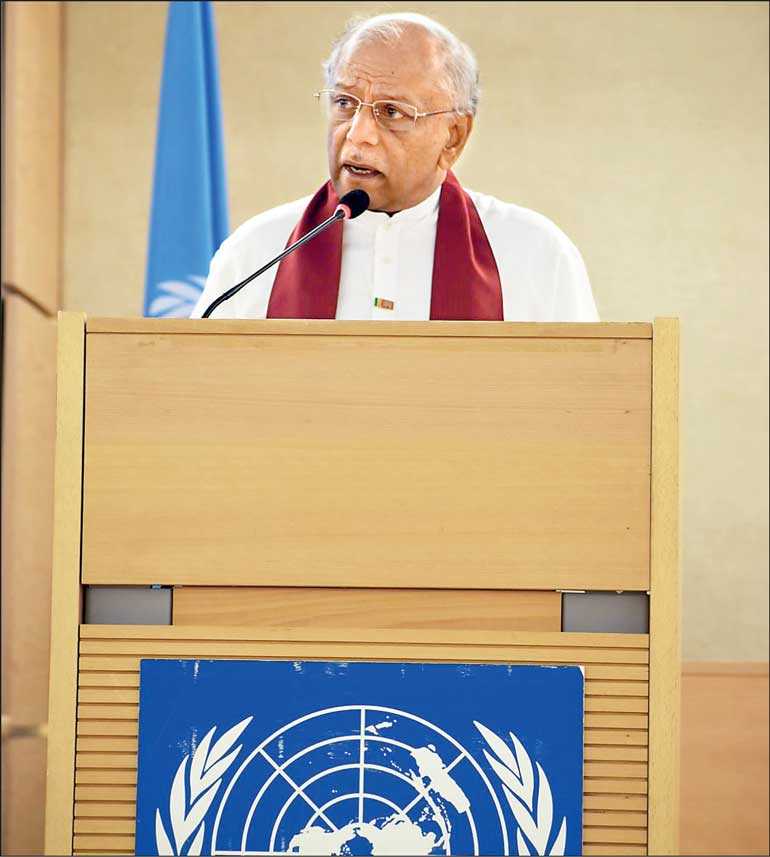

Following is the statement by Leader of Sri Lanka Delegation and Minister of Foreign Relations, Skills Development, Employment and Labour Relations Dinesh Gunawardena on 26 February at the 43rd Session of the Human Rights Council – High Level Segment

Madam President, Madam High Commissioner, members of the HRC and delegates, ladies and gentlemen, as this Council is aware, in November 2019, the people of Sri Lanka gave a resounding mandate to President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, to pursue a policy framework aimed at achieving the “fourfold outcome of a productive citizenry; a contented family, a disciplined, just society and a prosperous nation”1. It is envisaged to ensure sustainable development and peace in the country, firmly anchored in safeguarding “national security without compromising the democratic space available to our people”2.

1. The existential threat previously faced by Sri Lanka

Throughout the three-decade-long protracted terrorist conflict, while unleashing brutal terror attacks and killing tens of thousands of innocent civilians, the LTTE’s terrorism also denied fundamental freedoms not only to the people in LTTE dominated areas in the Northern and Eastern Provinces, but throughout the country. LTTE atrocities included ethnic cleansing campaigns, assassination of over one hundred democratically elected political leaders of all ethnicities, recruitment of young children as combatants, indiscriminate laying of mines in civilian areas and attacking critical infrastructure. As this august assembly is well aware, five attempts at peace talks by successive Sri Lankan Governments was unilaterally abrogated by the LTTE terrorists, who used these interludes from battle to re-arm, re-group and return to battle.

The closure of a vital sluice gate in the Eastern Province in July 2006, depriving tens of thousands of people access to water, left the then Government with no option but to launch a humanitarian operation to liberate the people of Sri Lanka from the clutches of the LTTE and to ensure the safety of all Sri Lankans from its unending terror campaign. The records of the meetings of the Consultative Committee on Humanitarian Assistance (CCHA) which was attended, inter-alia, by the co-chairs of the peace process and other international partners including UN agencies, clearly indicate that the Government of Sri Lanka made every effort to provide essential supplies and protect the lives of civilians in the conflict zone during the humanitarian operation.

It was over a decade ago, on 18 May 2009, that Sri Lanka defeated LTTE terrorism militarily, bringing to an end three decades of conflict and suffering. The end of the brutal conflict advanced, secured and protected one of the fundamental human rights – the ‘right to life’ for all Sri Lankans – Sinhalese, Tamils, Muslims and others. I would like to state with pride that since May 2009, not a bullet has been fired in the name of separatist terrorism in Sri Lanka. To date, the LTTE remains proscribed by 32 countries, which speaks of the world’s recognition of the abhorrent terrorist path they followed.

2. Post-conflict action by GoSL

Sri Lanka never had any illusion that the end of the conflict against LTTE terrorists will overnight convert to lasting peace. Although Sri Lanka was not a case of nation building, like many conflict situations that this Council is dealing with, we were mindful that Sri Lanka needed certain reviews and strengthening of existing structures, as part of a sustainable peace and reconciliation program.

The Government led by the then President Mahinda Rajapaksa, of which the current President Gotabaya Rajapaksa was the Secretary to the Ministry of Defence, guaranteed the safety of hundreds of thousands of civilians who started crossing over to the safety of Government controlled areas while the conflict was still ongoing. They also provided immediate humanitarian assistance soon after the defeat of terrorism to over 300,000 civilians who escaped the clutches of the LTTE, which had held them as human shields during the last phase. This was followed by the initiation of a sustainable reconciliation process in Sri Lanka to bring about ‘healing and peace building’, taking due cognisance of the ground realities at that time. This was viewed as an incremental and inclusive process, as it had taken even better-resourced countries several decades to address and achieve.

The Government of Sri Lanka at the time, of which I was a member, embarked on a process to work towards reconciliation, rebuilding, resettlement and rehabilitation. This process made considerable progress in all aspects of post-conflict restoration of civilian life and in the country’s return to normalcy.

The end of the three decade old conflict left a vast extent of land in the north and east (1311 sq. km) contaminated with a very high concentration of landmines and Unexploded Explosive Ordnances (UXOs) placed by the LTTE without records in civilian areas. This was a major impediment to the speedy resettlement of families returning to their homes after the conflict. Non-availability of mapping of mines and marking of areas where land mines were laid further complicated the issue. To overcome this challenge the security forces conducted a comprehensive demining operation in the north and east, which also received the technical support of several foreign governments and international agencies. As at December 2014, at the point the Mahinda Rajapaksa Government was concluding its term, 94% of the de-mining had already been completed, while presently it has risen to 98.7%. As a result, not a single incident of landmine explosion causing injuries to civilians has been reported, since the internally displaced were resettled.

Sri Lanka also made significant progress in the resettlement of over 440,000 IDPs3 and the development of infrastructure in the conflict affected areas. This was commended by the Director of the Coordination and Response Division of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs following his visit to the north in August 20124. As at December 2014 89.71% of the resettlement had been completed, while presently it has risen to 93.76%.

The Government accorded utmost priority to the expeditious release of land used by the security forces during the time of the conflict. As at December 2014, 71.01% of the private land had been completely returned to their owners, while presently it has risen to92.22%.

The high security zones designated during the conflict ceased to exist shortly after the end of the conflict. The Security Forces’ presence in the Jaffna peninsula had also significantly reduced by the end of 2014.

As this High-Level Segment of the Council deliberates on the theme of ‘implementation of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)’, I believe it is important to bring to the attention of this august body that, following the ending of the conflict, all child soldiers who had been forcibly conscripted by the LTTE were successfully rehabilitated and reintegrated into society by 2012.

Approximately 12,000 ex-LTTE combatants who surrendered at the end of the conflict were also rehabilitated and reintegrated. The Government did not pursue retributive justice against an overwhelming majority of these combatants, though they had, in fact, waged a separatist war against a sovereign, democratic state, as it was determined that this would stand in the way of reconciliation after decades of conflict.

A rapid infrastructure development programme was launched soon after the liberation of the north and east, with diverse programs implemented in the fields of transport and highways, railways, irrigation and agriculture, fisheries, power supply, education and financial services etc., ensuring provision of essential services to the community. These public sector driven investments resulted in a significant increase of the provincial GDP growth in the conflict-affected areas, which in 2012 even surpassed the national GDP.

Despite the introduction of the Provincial Councils in 1987, since 1989, the right to exercise franchise to the Northern provincial council was denied to residents of the Northern Province by the LTTE. A significant step in restoration of normalcy was that, in 2013, the citizens in the Northern Province were able to use their franchise after a lapse of 25 years, thus strengthening democracy. Elections for the Eastern Provincial Council were also held in May 2008 shortly after the liberation of the Eastern province.

In parallel, consistent with the pledges made to the people of Sri Lanka in the immediate aftermath of the conflict, several domestic mechanisms/commissions were established to address the post-conflict issues of concern, including those related to accountability, rule of law and human rights. The Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission5 and the Paranagama Commission6, had been providing updates on the home-grown reconciliation mechanism.

Notwithstanding these inclusive and locally designed measures undertaken, carrying along all people of Sri Lanka, a group of UNHRC members, failing to appreciate the GoSL’s endeavours in defeating terrorism, and bringing about stability, humanitarian relief and lasting peace through a carefully balanced reconciliation process, moved consecutive country-specific resolutions at the UN HRC on Sri Lanka in 2012, 2013 and 2014.

3. Resolution 30/1

The Government that came to power in Sri Lanka in January 2015 jettisoned this home-grown reconciliation process which was bearing fruit. In an unprecedented move in the annals of the Human Rights Council, and contrary to Sri Lanka’s stance on country specific resolutions, this Government co-sponsored the UNHRC resolution 30/1.

Neither the OISL report of 2015 nor Resolution 30/1 had factored in the aforementioned very important elements or activities undertaken by the Mahinda Rajapaksa Government. The framework for reconciliation, accountability and ensuring sustainable peace which had already been initiated and pursued prior to 2015, were ignored to the detriment of Sri Lanka.

Substantively, the previous Government “noted with appreciation”, the much flawed OHCHR Investigation on Sri Lanka (OISL) Report, which was used as the basis not only for Resolution 30/1, but also to unjustly vilify the heroic Sri Lankan security forces, possibly the only national security establishment that defeated terrorism in recent times. This was despite the report itself admitting that the OISL constituted only a “human rights investigation and not a criminal investigation”7, basing itself on information and testimonies of which neither the source nor its credibility could be verified. Further, there was an abundance of evidence to the contrary, contained in domestic reports such as the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) and the Presidential Commission of Inquiry into complains of alleged abductions and disappearances (the ‘Paranagama Commission’ chaired by a retired High Court Judge). The information presented before the UK House of Lords by Lord Naseby has also countered, among other things, the false narratives with regard to vastly exaggerated civilian casualty figures, based on a number of sources, including the reports from the UN Country Team, dispatches from the former UK Defence attaché, as well as remarks made by Ambassadors who were based in Colombo8. Reports from the UN and international agencies including the ICRC, as well as other exposed diplomatic cables also disproves the falsities.

Constitutionally, the Resolution seeks to cast upon Sri Lanka obligations that cannot be carried out within its constitutional framework, and it infringes the sovereignty of people of Sri Lanka and violates the basic structure of the Constitution. This is another factor that has prompted Sri Lanka to reconsider its position on co-sponsorship.

Procedurally, in co-sponsoring Resolution 30/1, the previous Government violated all democratic principles of governance. Having declared to support the resolution even before the draft text was presented, the Government sought no Cabinet approval to bind the country to deliver on the dictates of an international body. There was no reference to the Parliament, on the process, undertakings and repercussions of such co-sponsorship. More importantly, the Resolution itself included provisions which are undeliverable due to its inherent illegality being in violation of Sri Lanka’s Constitution, the supreme law of the country. It also overruled the reservations expressed by professional diplomats, academia, media and the general public. The then President Maithripala Sirisena also stated that he was not consulted on the matter at that time. It remains to date a blot on the sovereignty and dignity of Sri Lanka.

The commitments made bound the country to carry out this experiment, which was impractical, unconstitutional and undeliverable, despite strong opposition and evidence that many of the undertakings couldn’t be carried out, merely to please a few countries.

In terms of reputational damage, it has eroded Sri Lankans’ trust in the international system and the credibility of Sri Lanka as a whole in the eyes of the international community. This irresponsible action also damaged long nurtured regional relationships and Non-Aligned as well as South Asian solidarity. The deliberate polarisation it sought to cause through trade-offs that resulted in Sri Lanka’s foreign policy being reduced to a ‘zero-sum game’, made my country a ‘pawn’ on the chess board of global politics, and unnecessarily drew Sri Lanka away from its traditional neutrality.

Most seriously, it is seen that the dictated changes in the country pursuant to 30/1, undermined national interest, compromised national security, including the weakening of national intelligence operations and related safeguards, which are deemed to have contributed to the lapses that resulted in the Easter Sunday attacks in April 2019, which targeted churches and hotels, resulting in loss of life, including those of foreign nationals, which pose challenges to our Government to restore national security.

It is ironic that, in March 2019, the previous Government which co-sponsored Resolution 30/1 in October 2015, began the process of dismantling its dictates through the statement made in this Council by my predecessor, which acknowledged the very real constraints that had been ignored 4 years before, at the time of co-sponsoring this Resolution. That statement sought to qualify the parameters of co-sponsorship of the Resolution. It questioned the Resolution 30/1’s characterisation of the nature of the conflict and the estimated number of deaths, pushed back on the alleged culpability of the security forces, curtailed the effect of security sector reform demanded, and asserted that the Sri Lanka Constitution precludes involvement of foreign judges and prosecutors in the judicial mechanism proposed. Notwithstanding this admission, the former Government continued its co-sponsorship, which fully supported the operationalisation of Resolution 30/1.

4. New GoSL position on the Resolution

With the election of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa with an overwhelming majority, the people of Sri Lanka have given a clear signal for their wish for a different path forward for the country. As President Rajapaksa stated in his address at the 72nd Commemoration of Independence of Sri Lanka, “We will always defend the right of every Sri Lankan citizen to participate in the political and governance processes through his or her elected representatives”.

According to the wishes of the people of Sri Lanka, while following a non-aligned, neutral foreign policy, our Government is committed to examining issues afresh, to forge ahead with its agenda for ‘prosperity through security and development’, and find home-grown solutions to overcome contemporary challenges in the best interest of all Sri Lankans.

It is in this context that I wish to place on record, Sri Lanka’s decision to withdraw from co-sponsorship of Resolution 40/1 on ‘Promoting reconciliation, accountability and human rights in Sri Lanka’ which also incorporates and builds on preceding Resolutions 30/1 of October 2015 and 34/1 of March 2017.

5. Way forward

Notwithstanding withdrawing from co-sponsorship of this resolution, Sri Lanka remains committed to achieving the goals set by the people of Sri Lanka on accountability and human rights, towards sustainable peace and reconciliation. To this end;

a) The Government of Sri Lanka declares its commitment to achieve sustainable peace through an inclusive, domestically designed and executed reconciliation and accountability process, including through the appropriate adaptation of existing mechanisms, in line with the Government’s policy framework. This would comprise the appointment of a Commission of Inquiry (COI) headed by a Justice of the Supreme Court, to review the reports of previous Sri Lankan COIs which investigated alleged violations of Human Rights and International Humanitarian Law (IHL), to assess the status of implementation of their recommendations and to propose deliverable measures to implement them, keeping in line with the new Government’s policy.

b) The Government will also address other outstanding concerns and introduce institutional reforms where necessary, in a manner consistent with Sri Lanka’s commitments, including to the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda (SDGs). We will implement policies rooted in the Government’s commitment to the people by advancing individual and collective rights and protections under the law, ensuring justice and reconciliation and addressing the concerns of vulnerable sections of society. Special attention will be paid to environmental protection in the formulation and implementation of Government policies. The President, in his policy statement at the inauguration of the Fourth Session of the eighth Parliament of Sri Lanka, reiterated his vision to make “Sri Lanka one of the world’s leading nations in achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals”. A discussion has already been held between the President and the UN Resident Coordinator where it has been agreed to connect the relevant UN agencies to assist the Government of Sri Lanka in the implementation of the SDGs.

c) Sri Lanka will continue to remain engaged with, and seek, as required, the assistance of the UN and its agencies, including the regular human rights mandates/bodies and mechanisms, in capacity building and technical assistance, in keeping with domestic priorities and policies.

d) In conjunction with all members of the UN, Sri Lanka will seek to work towards the closure of the Resolution.

Conclusion

No one has the well-being of the multi-ethnic, multi-lingual, multi-religious and multicultural people of Sri Lanka closer to their heart, than the Government of Sri Lanka. It is this motivation that guides our commitment and resolve to move towards comprehensive reconciliation and an era of stable peace and prosperity for our people. It is therefore our strong conviction that the aforementioned actions within the framework of Sri Lanka’s domestic priorities and policies, are not only realistic but also deliverable. We call upon all stakeholders, within and outside this august body, to cooperate with Sri Lanka in this endeavour.

May I conclude quoting the words of Lord Buddha: “Siyalusathwayonidukwethwa, nirogeewethwa, suwapathwethwa.”

May all beings be safe, may all beings be free from suffering, may all beings be well and happy.

Thank you.

Footnotes

http://www.treasury.gov.lk/documents/10181/791429/FinalDovVer02+English.pdf/10e8fd3e-8b8d-452b-bb50-c2b053ea626c

2 Ibid

3 https://reliefweb.int/report/sri-lanka/ocha-director-operations-praises-progress-sri-lanka-and-appeals-donor-support

4 Ibid

5 https://847da763-17e4-489f-b78a-b09954fec199.filesusr.com/ugd/bd81c0_45c0a406040640818894ce01c0bd8ca3.pdf

6 https://847da763-17e4-489f-b78a-b09954fec199.filesusr.com/ugd/bd81c0_7dbfa86dfea6406ab9f89f641f8a5a2f.pdf https://847da763-17e4-489f-b78a-b09954fec199.filesusr.com/ugd/bd81c0_02a8e91c18ab47359763b405c2d9f89e.pdf

7 Report of the OHCHR Investigation on Sri Lanka (OISL), A/HRC/30/CRP.2 of 16 September 2015, para. 5 (Page 5) “It is important at the outset to stress that the OISL conducted a human rights investigation, not a criminal investigation.” and para. 33 (Page 10)

8 https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/2017-10-12/debates/14CAA83D-8895-4182-8C4F-D964E0A5B399/SriLanka