Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Wednesday, 6 June 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By G.D. Kapila Kumara

Economists identify two major factors of production which determine the level of output of a country. They are labour and capital. Thus, quantity and quality of labour force in a country plays a vital role in its development process.

The age structure of a population, particularly working aged population, determines the quantity of labour force, while health and education sectors determine the quality of labour force. The age structure of a population varies over time, and thus working aged population. Accordingly, periodical changes in the age structure of a population open windows of opportunities for the respective country for a certain period of time for enjoying with high labour force and less number of dependents. This process is technically termed as ‘Demographic Dividend’ or ‘Demographic Bonus’.

The demographic dividend is simply defined as a favourable effect of an increase in the share of working aged population on economic growth (United Nations Population Fund, 2011). There are two types of demographic dividends. The first demographic dividend is recognised by the growth rate of the economic support ratio and the second demographic dividend is derived from capital accumulation that could generate sustainable economic growth.

Demographic dividend is a natural phenomenon and does not provide automatic benefits. Proper plans and their implementations only make it real. For example, countries like Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong which are known as four Asian Tigers or Asian Dragons made use of this opportunity and became developed nations within a short period of time. Among other factors, effective utilisation of demographic dividend is a major factor behind the success of Asian Tigers (Mason, 2007).

Thailand is also another success story (United Nations Population Fund, (2011), “Impact of Demographic Change in Thailand”).

A country that goes through demographic transition must not miss the opportunity because demographic deficit (the period where aging the population) will follow demographic dividend. The aging population gradually lower the labour force and increase the number of adult dependents, creating serious social and economic problems. Countries that successfully capitalised demographic dividend, such as Japan and South Korea, can overcome such complications associated with demographic deficit with less burden, and vice versa.

Sri Lanka experienced its demographic dividend for 45 years from 1970 to 2015 (Navaneetham, 2002). However, it is doubtful whether Sri Lanka reaped the full benefits of its demographic dividend or not. As pointed out before, demographic dividend is not automatic. A country that experiences demographic dividend cannot reap its complete benefits without right policies in place. Thus, in this report, I attempt to analyse Sri Lanka’s effort in capitalising the demographic dividend. Moreover, I wish to compare Sri Lanka’s scenario with Thailand, a success story in capitalising demographic dividend as a development strategy.

Sri Lanka and Thailand

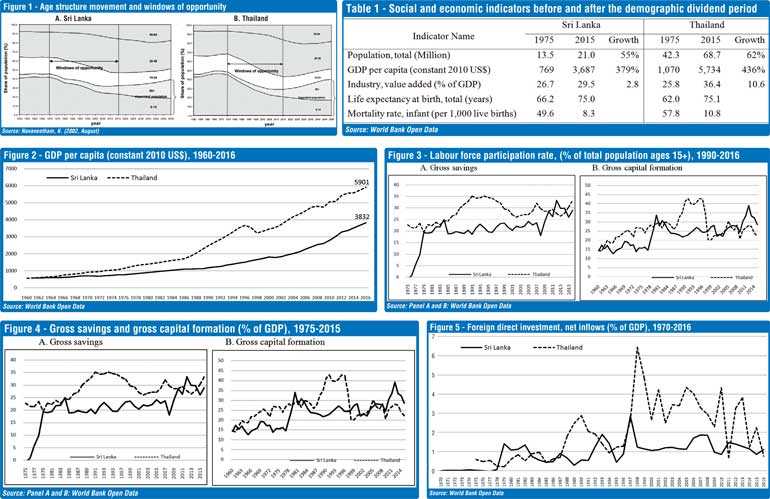

As shown in figure-1, the period of demographic dividend of Sri Lanka and Thailand spans from 1970 to 2015 and 1975 to 2015 respectively (Navaneetham, 2002), which are almost similar to each other. The table-1 summarises some selected social and economic indicators of both countries before and after the dividend period. Accordingly, Thailand has performed well during the respective period compared with Sri Lanka. Thailand’s GDP per capita grew by 436percentduring the period of demographic dividend while Sri Lanka recorded a growth of 379 percent.

As figure-2 clearly indicates, although Sri Lanka and Thailand were in the same level of GDP per capita in 1960s, Thailand managed to maintain high and robust economic growth over the period. However, the success story was not that rosy. Thailand experienced a severe economic shock in 1997 due to Asian Economic Crisis. However, Thailand managed to recover quickly and continued journey of success. Thus, looking at many economic indicators, it is obvious that Thailand is far ahead of Sri Lanka in terms of capitalising demographic dividend.

Why did Sri Lanka lag behind Thailand in terms of capitalising demographic dividend?

It seems that Sri Lanka could not reap the full benefits of demographic dividend, may be due to failure in placing right policies at right time. The Population Reference Bureau (2013) points out four particular areas in which strategic investments are required to made in order to capitalise the benefits of demographic dividend. They are health, education, economic policy, and governance. Let’s look at Sri Lanka’s commitment in these four areas to figure out where Sri Lanka went wrong in this process.

The performance in both health and education sectors are key in developing human capital. Sri Lanka’s health indicators are satisfactory compared with other Asian peers and almost equal to developed countries.

In case of education, the second factor, Sri Lanka’s performance is not pleasing. Although literacy rate is high (around 93%) (Central Bank of Sri Lanka, 2017), high unemployment rate among educated youth in Sri Lanka shows a skill mismatch in labour market. Sri Lanka’s unemployment rate among advanced educated people is approximately 11% while it is just around 1percent in Thailand (World Bank Open Data). This implies that Sri Lanka has failed in updating education system in timely manner according to the requirements of labour market.

Apart from skill mismatch, failure in revising the labour law, according to the changes in the social and economic order, resulted lower level of labour force participation rate over the past decade. As shown in figure 3, Sri Lanka’s labour force participation rate (53%) has been significantly less than Thailand (68%) over the past decade. This gap is more severe among the working aged female population (around 25%).

Factors like demand-side constraints on the participation of women in the labour force such as occupational segregation, discriminative employment conditions (particularly in wages), less availability of quality jobs, and lack of entrepreneurship opportunities for women keep female participants away from the labour force (International Labor Organization, ‘Women labour force participation in Sri Lanka’ (2016). This implies that Sri Lanka has miscarried in attracting a considerable share of working aged population to the labour force through right policy implementations.

Right economic policies, the third factor, are necessary to encourage savings and investments so that the economy can absorb its growing labour force. Thailand demonstrates that demographic dividend can be realised through right economic policies. Figure 4 shows saving and investment in two countries. Thailand has outperformed Sri Lanka over the decades in both savings and investments.

In this process, the role of the government matters. Thai government guarantees for free business activity not only for domestic enterprises, but also for foreign companies. The results of Thai government’s commitment is reflected by international rankings. According to the ‘Ease of Doing Business Index’ Thailand is ranked as one of the best countries in the world in doing business (26th position), far ahead of the Sri Lanka (111th position) (Doing Business 2018).

In analysing Thailand’s success in economic policy formulation, the policies related with Small and Medium sized enterprises (SME) such as One Village One Product program and introducing SME Banks created a significant impact, particularly after the recovery period of the Economic crisis.

The policy directions in developing the automotive industry is a key milestone in Thailand’s economic history. The automotive industry currently contributes approximately 12percent of Thailand’s GDP (Assessment of Thailand’s Auto Sector, 2017). These facts show that Thailand was more successful than Sri Lanka in nurturing a conducive environment for businesses through formulating supportive economic policies and implementation of them in a way they can fully utilise the demographic dividend.

Thailand successfully controlled its unemployment level less than 1% on average over past decade thanks to raised domestic enterprises and foreign direct investments (FDI). Figure 5 shows that Thailand has outperformed Sri Lanka in attracting FDI. Although Sri Lanka managed to control its unemployment level less than 5%, the figure does not reflect real unemployment condition in the country due to low level of labour force participation rate and increased labour migration (World Bank Open Data).

The fourth and the last factor ‘governance’ represents political stability, rule of law, and transparency and accountability of institutions. These factors were badly affected by the 30 years’ civil war in Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka lost a considerable amount of physical and human resources due to the war. Apart from that, stagnation of infrastructure development, underutilisation of land and other resources, less tourist arrival, uncertainty in the economy and failure to attract adequate FDI drew back the country’s economic performance.

Summary and conclusion

Sri Lanka and Thailand experienced the demographic transition almost during the same period. However, Thailand was ahead of Sri Lanka in capitalising demographic dividend. Thailand occupied its human resources properly through right policy decisions and their implementation. Sri Lanka lagged behind Thailand in this process due to several reasons. They are the long civil war, low level of female labour force participation, skill mismatch in the labour market, high labour migration, failure to improve industry sector and attract adequate FDI.

(The writer is a visiting lecturer at University of Colombo and IPM.)