Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Friday, 26 February 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Merril Gunaratne

|

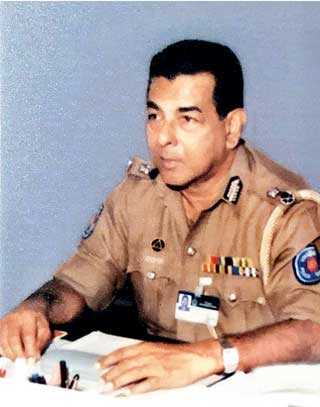

| Camillus Abeygunawardena |

Camillus and I were contemporaries of St. Peter’s College, Colombo in the 1950s, though in different

classes. After passing the S.S.C. exam, he chose the police for a career, and at a time when the service attracted talent in sports and studies.

Many other outstanding Peterites, some in sports, some with leadership skills, joined the police in the 1950s: Muni Gomes, Sivendran, Navaratnarajah, Lakshman Jayawardene, Maxie Fernando and Nissanka Dharmatillake. It is to the credit of the school which nursed and nourished them, that these stalwarts held not only the school, but the police flag high, and with pride. Camillus and his band without exception were honourable men who respected pristine values and ethics. Their careers were laced with standards and principles. What mattered to each of them was not the rank, but the way it was held. Naturally, they were a proud breed.

A recurring theme in my recent book, ‘Perils of a Profession’, was the irreparable harm caused to the service because self-seeking officers found space and scope to climb over those lying ahead in the line of seniority, merely because they had the backing of powerful patrons. I had also pointed out that those without patrons were left at the mercy of individuals who engaged in such plunder and cheating because seniors in the highest police echelons stood mute without offering resistance.

Camillus Abeygoonewardena and Muni Gomes had powerful patrons in support, when serving as security officers to president J.R. Jayewardene. But they did not seek to acquire such ‘backdoor’ promotions, increments, lands or houses. Such honourable conduct deserves the highest praise, for they resisted greed and selfishness in an emerging environment conducive for the acquisition of posts and promotions through dishonourable means. Camillus and those of his ilk were upright, proud, honest and honourable men who eschewed material assets, exuberance, excesses, abuse and double standards. Camillus had deep respect at all times for standards, justice, the rule of law, fairplay and discipline. In his own persuasive style, he often held his ground when having to disagree with his superiors or the establishment, on professional matters.

The police service as a career has much to offer by way of temptations which are not consonant with ethics and values expected of the profession. At no point of time in an illustrious career did Camillus succumb to them. He joined the service with modest means, and left the same way. Nor was he selfish to the point of acquiring benefits, though being in the proximate presence of powerful patrons. Many others who joined the police in the 1950s, including his Peterite colleagues, were no exception. Their professional lives were also laced with honour, pride, simplicity, respect for the law and honesty. It was an era when such role models were plenty. Exuberance, excess and subservience were not in their armour. This breed which is now extinct, stands in sharp contrast to the police of latter days.

I remember the time somewhere in 1960 when I met Camillus after we left school. I was then an undergrad in the University of Ceylon, Peradeniya, while he was a Sub Inspector. I was in the gymnasium when he walked briskly up to me to renew acquaintances. My first impression was the friendly manner in which he spoke with me. Despite being a Sub Inspector, a rank highly respected in bygone times, he displayed modesty and simplicity.

We next met after I joined as a ‘cop’. Camillus came into prominence for his outstanding work in the ‘Traffic and Transport’ committee which performed admirably at the Non-aligned Summit of 1976, being the ‘anchor’ to late senior DIG Leo Perera who was the chairman. They together handled the complexities of innumerable motorcades of such a galaxy of VIPs with excellent timing, precision and panache. Being then in the ‘Security Committee’, I had abundant opportunity to observe the dignified, calm, confident and efficient performance of Camillus.

Being obsessed with traffic work, he chose it for a career. It is my view, and I have said so in my book, ‘Perils of a Profession’, that he was the best exponent in the field in my time. I had ample opportunity to witness a stellar performance by him on the occasion of the visit of his Holiness the Pope to Sri Lanka in 1995. Let me quote from my book (page 80): “I must make special mention of DIG Camillus Abeygoonawardane who as Director of Traffic of the Colombo Range won the appreciation of the public for his excellent traffic plans. He was probably the best traffic enforcer in the country at the time.”

Camillus and traffic were synonymous. His advice was regularly sought in respect of complications which arose amidst a splurge of motor vehicles causing endless obstructions on the highways. It was my firm opinion that the skills of this officer who was a master of the trade were not adequately harnessed, when in service. In fact, I proposed, when serving as an ‘Advisor’ in the ministry of defence in 2002, that he should serve in a ‘project ministry’ for traffic, given the chronic state of traffic complications, particularly in Western Province. I did not even receive an acknowledgement for my proposal!

Camillus displayed considerable drive and initiative in whatever he undertook. He was a key member of the Committee of the Senior Police Officers Mess of which I was the president in 1992-93. I took over when the Mess was poised to undergo a major revamp. We together virtually achieved a ‘miracle’, transforming it to unimaginable standards. The enthusiasm of Camillus and his suggestions as an innovator were remarkable. I was so fortunate to have been blessed with his association in this endeavour. Such improvements could not have been achieved without the zest and dynamism of Camillus.

After an exquisite ‘bar’ of the highest quality saw creation, Camillus, his initiative knowing no limits, produced an acquaintance who, for a mere two bottles of arrack, produced two beautiful paintings for the bar. Sadly, the two paintings are now missing, as well as the highly valued crimson carpets which adorned the bar and the “IG’s Lounge”. What happened to them later remains a mystery. Far worse, marble floors replaced the rich carpets, an incongruous sight! What looked awesome became awful.

Camillus was also an excellent organiser, administrator and coordinator. He held several positions where such skills were in demand. He was a president of the Old Boys Association (OBA) of St. Peters College, President of the Retired Senior Police Officers Association (RSPOA) and a president of the Nondescript Cricket Club (NCC). He also played a leading role in the emergence of St Peters’ College as a formidable team in Rugby. Incidentally, his sons were excellent ruggerites, doing the school proud. Sadly, one of them passed away, two years ago.

In the years following 1977 when the environment became propitious for quite a number of officers spurred by greed to plunder positions and promotions, Camillus refrained from joining them. He was cast in a different mould. He represented a coterie of officers which believed that rank cadre should increase to serve the interests of the service, not individual interest. They were too upright to stoop low.

Camillus embellished the service with respect for standards and pristine precedents, and by displaying a remarkable drive for initiative and efficiency. He stood tall when the police descent to decline began to grow in intensity amidst outside interferences, helped by inertia amongst those in the highest echelons of the police. He was the epitome of that extinct breed of officers which made the police the envy of many. Camillus and his kind were beacons amidst the gathering gloom, turmoil and tensions.

His wife Mali and sons Sanjeewa and Dilan have every reason, despite the grief, to be proud that Camillus has left them unforgettable memories: an honourable name, and prestige earned for extraordinary efficiency and the observance of noble standards.