Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Saturday, 24 October 2020 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

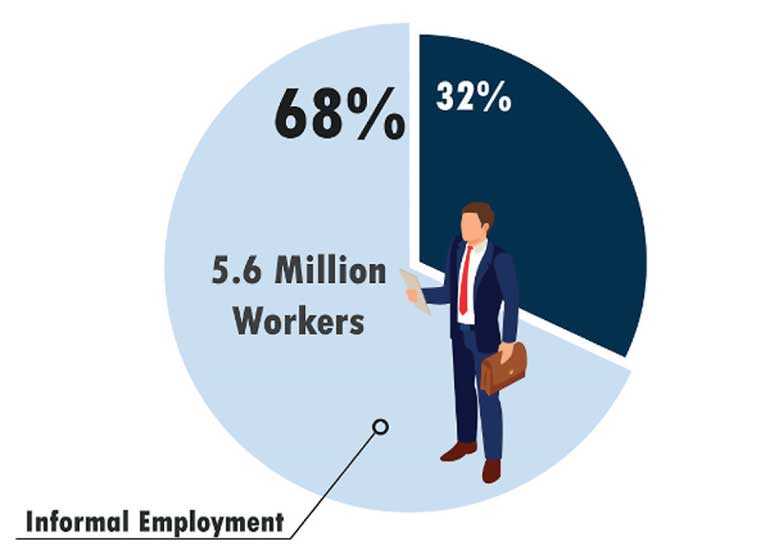

While Government expenditure acts as a key stimulus during crises, Sri Lanka does not possess the macroeconomic stability to offer such a package. The repercussions of this are primarily felt by informal sector workers who make up 68% of Sri Lanka’s workforce

By Harini Weerasekera

The Sri Lankan economy is likely to face a contraction in 2020 as a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic but there is potential for this to be followed by a sharp V-shaped economic recovery. The means of navigating such a recovery path were discussed at a webinar panel discussion held last Thursday (15 October) to mark the release of the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka’s (IPS) flagship report ‘Sri Lanka: State of the Economy 2020’.

The Sri Lankan economy is likely to face a contraction in 2020 as a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic but there is potential for this to be followed by a sharp V-shaped economic recovery. The means of navigating such a recovery path were discussed at a webinar panel discussion held last Thursday (15 October) to mark the release of the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka’s (IPS) flagship report ‘Sri Lanka: State of the Economy 2020’.

Macroeconomy: Getting public finances in order

IPS Executive Director Dr. Dushni Weerakoon stated that the key macroeconomic challenge Sri Lanka has to contend with is its mounting debt. This is not a new issue, but one that has built up progressively over the last decade, where a shock like COVID-19 simply makes dealing with such a debt burden much more challenging. A large debt overhang does not allow for the implementation of a crisis mitigation strategy or an economic stimulus package of the desired size, to match the scale and complexity of the current pandemic.

The medium-term recovery path outlined by Dr. Weerakoon comprises of temporary measures to jump-start economic growth, which should then be followed by productivity-driven growth with technology infusion that is more sustainable in the long-term. Specifically, a quick-win strategy would be infusions to the infrastructure sector; attracting FDI into sectors such as construction can aid in jump-starting the recovery process. However, policymakers must recognise this as a temporary measure and not lean on such measures as the main driver of economic growth in the post-recovery phase.

Dr. Weerakoon contended that import restrictions are ‘understandable’ at this juncture but should be viewed as an emergency measure to protect employment but must eventually be re-aligned ‘based on global value chain recovery’. With rapid structural changes taking place, value chains are also restructuring and becoming more compact. Sri Lanka cannot afford to hold on to protectionist measures and miss out on breaking into these new regional production structures.

Private sector perspectives

Dilmah Ceylon Tea CEO Dilhan Fernando said that the COVID-19 crisis has exposed several structural weaknesses in the business world. The pandemic has shown that businesses must now ascribe value to education and healthcare, which were once considered costs, and that these will be vital components in ‘building back better’.

He stressed on the need to improve the country’s export competitiveness and productivity and asserted that integrating technology and value addition is the way forward, similar to what is practiced in the tea industry. Currently, the market is demanding features like traceability of products, ethical business practices and sustainability so businesses must adapt to these evolving demands.

Commenting on the tourism sector, he flagged the need to focus on refining processes, training employees and looking at ways to rebuild to engage consumers, even though the sector cannot receive them in full capacity at present. He stated that pent-up demand will build up for better times, so the best option is to prepare for it in the interim.

Widening disparities

IPS Director of Research Dr. Nisha Arunatilake said that the Government’s relief package to workers was comprehensive, but small relative to other middle-income economies. While Government expenditure acts as a key stimulus during crises, Sri Lanka does not possess the macroeconomic stability to offer such a package. The repercussions of this are primarily felt by informal sector workers who make up 68% of Sri Lanka’s workforce. Such workers will experience a decline in savings and resort to coping mechanisms such as foregoing investments in education and health, thus widening already existing inequalities.

She stated that the country’s macroeconomic constraints also limit the Government’s ability to keep the education sector afloat, during and in the aftermath of the pandemic. There were constraints in providing an integrated response of the nature seen in other countries where state resources were deployed to reach all students through multiple channels such as television, social media, etc. Instead, in Sri Lanka, individual schools and other educational institutions were left to their own devices, which intensify disparities. A significant proportion of households with school-going children do not have access to smart phones/computers (52%) and the internet (66%) which affects educational outcomes and exacerbates inequalities in the long run.

Another aspect discussed was gender inequality, where women tend to be disproportionately affected by the pandemic. On the one hand, flexible working arrangements can create more opportunities for women, but these benefits will be primarily accrued by skilled female workers. On the other hand, it is the large majority of female informal sector workers who are not covered by social protection schemes, who will be rendered more vulnerable than their male counterparts. She stressed that the solution lies in better disaster risk management systems – similar to that in Sri Lanka’s health sector, which had the apparatus in place to prepare for and deal with the crisis.

Way forward

Sri Lanka must make some important policy choices to ensure an effective post-pandemic economic recovery. There is a need for a sound fiscal policy including better tax and spending policies as a central requirement to address wide-ranging challenges including the debt burden, providing remote-education opportunities for all, and protecting workers and businesses without entrenching existing disparities, in the time of COVID-19.

(The writer is a Research Officer at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka with research interests in the areas of taxation, labour and migration, and econometrics and economic modelling. She holds a BSc in Economics from University of London International Programmes and a BA in Economics from the University of Colombo, with First Class Honours. She also graduated with an MSc in Economics from the University of Warwick where she authored a thesis on border tax evasion in Sri Lanka.)