Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Wednesday Feb 25, 2026

Thursday, 19 December 2019 00:25 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Patrick Mendis and Joey Wang

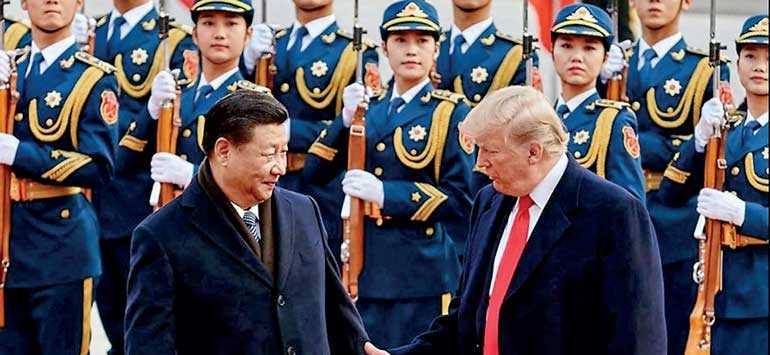

Ever since President Xi Jinping announced China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ (OBOR) strategy, now called the Belt Road Initiative (BRI, in 2013, the United States has sought to thwart, obstruct or counter the Beijing initiative.

The latest of these efforts comes in the ambiguous form of the Blue Dot Network (BDN) scheme, which was announced on the sidelines of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Summit in Bangkok, Thailand in November 2019.

Leading the American delegation—with the conspicuous absence of President Donald Trump at the summit - Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross told reporters in a conference call that “we have no intention of vacating our military or geopolitical position” in the Indo-Pacific region. To illustrate President Donald Trump’s commitment, US officials launched the administration’s BDN blueprint in several ways at different times and venues of the ASEAN Summit. Initially, the BDN was officially announced by a representative of the US Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) at the Indo-Pacific Business Forum in Bangkok, which was attended by some 1,000 people, including more than 200 American corporate executives.

Driven by the Washington-based OPIC—in partnership with the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC)— the BDN was meant to serve as a multi-stakeholder initiative that would harness governments, the private sector and civil society to “promote high-quality, trusted standards for global infrastructure development in an open and inclusive framework.”

The details of BDN were later unveiled at a panel discussion of representatives from OPIC, DFAT and JBIC. The US Undersecretary of State for Economic Growth, Energy and the Environment Keith Krach claimed that “this endorsement of Blue Dot Network not only created a solid foundation for infrastructure global trust standards but reinforced the need for the establishment of umbrella global trust standards in other sectors, including digital, mining, financial services and research” in the Indo-Pacific and around the world.

Lack of brain trust

It is not just the manner of the lower level of government official engagements on the sidelines of a summit but also their claims that raise a number of larger questions. For example, the yet-to-be formalised BDN agreement reached by the US, Australia and Japan can hardly be considered “global”. Nor can it be constituted as a “standard”.

Krach goes on to assert that “such global trust standards, which are based on respect for transparency and accountability, sovereignty of property and resources, local labour and human rights, rule of law, the environment and sound governance practices in procurement and financing, have been driven not just by private sector companies and civil society but also by governments around the world.”

To these assertions, Peter McCawley of the Lowy Institute in Australia has raised a range of important questions: “What does all of this mean? What sort of global trust standards are we talking about? Who will set the standards? And who will monitor them?”

Interestingly, new White House National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien maintained that the BDN scheme was designed to counter China’s BRI projects that were not considered to be “high quality”.

Indeed, it was an allusion to American platitudes, and Western nations in general, that Beijing was luring developing nations into debt-trap diplomacy. On the sidelines of the ASEAN Summit, O’Brien earlier accused Beijing of “intimidation” in the South China Sea, stating that smaller countries should not give up on their sovereignty and resources in disputed waterways to the Chinese “conquest”. President Trump’s advisor then explained that “Beijing has used intimidation to try to stop ASEAN nations from exploiting offshore resources, blocking access to $ 2.5 trillion dollars of oil and gas reserves alone”.

New exceptionalism and Sri Lanka

These pronouncements would suggest that the BDN scheme has not only missed its target, but also smacks a bit of paternalism.

First of all, there is some truth to these American claims. Many of these BRI countries have some of the highest levels of corruption and the lowest levels of transparency in their public sector, according to Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index. Among China’s western neighbors, through which the BRI runs—countries such as Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan—as well as most of the countries on the African continent, all rank among the worst in the world. As to risk factors, all have some level, or a significant level, of debt risk, both operational and economic. According to Moody’s Investors Service, only 25% of the 130 countries that have signed BRI cooperation agreements have an investment grade rating: “Forty-three percent have junk bond status, while a further 32% are unrated.”

In addition, it should be remembered that it is virtually impossible to achieve a high degree of precision on the level of China’s loans overseas to the developing world. Generally, China funds BRI projects through its policy banks, such as the China Development Bank, the Export-Import Bank of China and through State-Owned Enterprises. Neither the banks nor the recipients themselves share the rates at which these loans are made. The Paris Club, which tracks sovereign bilateral borrowing, would normally track these transactions. However, since China is not a member of the Paris Club, it “has not been subject to the standard disclosure requirements.” Therefore, China does not provide its direct lending activities related to BRI.

An extensive research analysis by the US National Bureau of Economic Research concludes that nearly a half of China’s loans to the developing world are “hidden”.

One of the most compelling cases was Sri Lanka. After being unable to repay $ 1.4 billion in loans for the Hambantota Port, the Sri Lankan Government not only handed over a 99-year lease, but a year later went back for a billion-dollar loan for highway construction.

Even in the Maldives, again, politics intervened, even as the Government is still unwilling to back off some of these key projects. In Malaysia, there is a $ 20 billion rail project, and the Chinese are now offering—because they are flexible, because they are learning—to cut the price in half, and Malaysia might end up going forward with it. According to an analysis by the Brookings Institution, recipient countries in general still find the BRI packages persuasive.

Missing pieces in Sri Lanka

Nonetheless, the BDN misses the mark on a number of counts. First, Sri Lanka’s widely reported debt trap, the Hambantota Port, remains a poorly conceived white elephant project that has insufficient revenue to service the loan. Hence, the Sri Lankan Government asked China to take over the port as the debt-for-equity swap proposed by the Colombo administration. It was hardly a Chinese intent to set a trap.

In its April 2019 analysis on ‘New Data on the “Debt Trap” Question’, the Rhodium Group states that “Sri Lanka’s decision in December 2017 to grant a 99-year concession to China on the Hambantota Port, and to agree to China Merchant Port Holdings acquiring 70% of the port’s operating company, serves as a cautionary tale of the dangers attached to countries’ overreliance upon Chinese financing.”

The Sri Lankan case of asset seizure is more of an outlier than being representative of the BRI projects surveyed. The Rhodium report then concludes that “actual asset seizures are a very rare occurrence. Apart from Sri Lanka, the only other example we could find of an outright asset seizure was in Tajikistan, where the Government reportedly ceded 1,158 km2 of land to China in 2011.”

All these analyses—by the Rhodium Group, the Brookings Institutions and Moody’s Analytics—indicate that most BRI nations do have varying levels of debt burdens, some significantly. However, the debt remains manageable for the most part. The debt vulnerability involved depends in part on how much increasing investments correlate with economic growth and productivity.

Further, these analyses reveal that China’s lending practices do not follow any specific pattern in the debt profiles of recipient countries or the levels of governance. China has lent to both authoritarian governments as well democratic ones, and with varying degrees of debt. More interesting is the fact that Beijing will sometimes write off debts without a formal renegotiation process. Instead, it “usually unilaterally agrees to cancel part of a borrowing country’s debt, even when there are few signs of financial stress on the part of the borrower.”

These cases of debt forgiveness likely suggest that the debt itself is less important than the objective of improving bilateral relations and diplomacy. This points to where BDN misses the mark on the second count.

While the BDN focuses on “global trust standards” and “high quality” loans, the BRI is not a monolithic infrastructure investment agenda. Rather, it clearly reflects “a blend of economic, political and strategic agendas that play out differently in different countries, which is illustrated by China’s approach to resolving debt, accepting payment in cash, commodities or the lease of assets.”

The strategic objectives are especially apparent where access to key ports and waterways is aligned with Beijing’s investment and diplomatic priorities.

White House eyes wide shut

The continuing debt trap narrative appears to be driving the idea that developing nations do not have the financial nor technocratic savvy to avoid a debt trap, which has not been the case. Some countries have now learned from the Sri Lanka experience and have recognised that the costs far outweigh the benefits.

Bangladesh for instance has declined Chinese funding for much-needed “20-km-long rail and road bridges over the Padma River” and has instead opted for “self-generated funds”. Citing China’s “unfair” infrastructure deals by his predecessor, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad cancelled two projects: the East Coast Rail Link, which would have connected Port Klang on the Straits of Malacca with the city of Kota Bharu and a natural gas pipeline in Sabah. While the Sabah pipeline project remains annulled, the East Coast Rail Link restarted only after China agreed to cut the price by nearly $ 11 billion. Thailand is also working to create a regional infrastructure fund via the Ayeyawady-Chao Phraya-Mekong Economic Cooperation Strategy to reduce reliance on China. While not technically a developing nation (but an ‘upper-middle income country’), Jamaica has recently decided not to negotiate any new loans from China, citing its commitment to reducing its debt.

It is hard to know whether the US misinterpreted Chinese BRI intentions, or simply went into the BDN scheme with their eyes wide shut while obscuring the American quest for a new military strategy. Either way, the Brookings Institution’s ‘China’s Belt and Road: The New Geopolitics of Global Infrastructure Development’ pointed out that while China did recognise a significant infrastructure gap along its periphery, there has never been any secret about the profit motives for the BRI.

Certainly, it is true that the developing world needs infrastructure development. But beyond the platonic high-mindedness of these ideals, it is not at all clear what better alternative the developing world can expect from BDN since it will have “no lending function” of its own according to the Financial Times.

The BRI came in to fill the void because international financial institutions—including the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the African Development Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank—have largely shifted away from investing in infrastructure development projects.

The US and the West can excoriate China all it wants for China’s debt traps, lack of transparency and pernicious diplomacy but unless the US and the West come up with better solutions, that dirt road—for Sri Lanka and other developing world—is still a dirt road.

(Dr. Mendis is a distinguished visiting Professor of Global Affairs at the National Chengchi University and a Senior Fellow of the Taiwan Center for Security Studies in Taipei. He previously served as a distinguished Visiting Professor of Sino-American Relations at the Yenching Academy of Peking University, a Rajawali Senior Fellow of the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University and a Commissioner to the United States National Commission for UNESCO at the US Department of State. Joey Wang is a Defence Analyst. Both are alumni of the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. The opinions expressed in this article are their own and are not reflective of their affiliations to their past or present institutions.)