Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Wednesday, 16 September 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

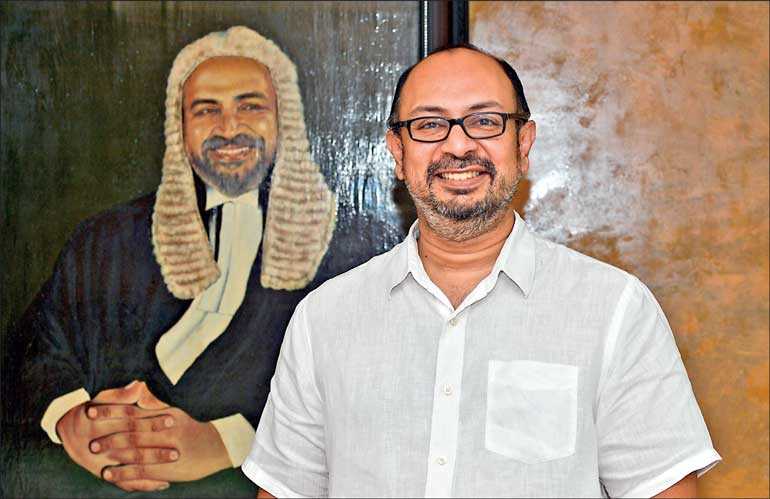

Aman Ashraff with a portrait of his late father in the background - Pix by Daminda Harsha Perera

Today marks the 20th death anniversary of M.H.M. Ashraff, the Founder Leader of the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC). He died on 16 September 2000, when the Sri Lanka Air Force (SLAF) helicopter he was travelling in crashed in the Aranayaka area in Kegalle District, leaving a void in the political sphere of the country, in which he was a rising star. In an exclusive interview with the Daily FT, Aman Ashraff, the son of the late SLMC Leader, spoke on a wide range of issues and gave his views on his father’s death, over which many questions remain unanswered. He also spoke on the challenges the community faces in the aftermath of the Easter Sunday attacks and the need for all to work towards building a Sri Lankan identity. Here are excerpts of the interview:

By Chandani Kirinde

Q: The official versions of the helicopter crash that caused your father’s death say it was accidental. Twenty years later how do you see the tragedy?

After 20 years, having observed the dynamics since his demise, I find it hard to accept that it was an accident. There may have been a lot more to it than that. Of course, I have no evidence or anything substantial to hold onto and say, ‘This is there, so how do you say that?’ I do not intend to accuse anybody, but as an individual, not so much as his son, I feel there was more than meets the eye.

Q: If so, who do you think would want him out of the way or who do you perceive as his enemies?

He was certainly on the LTTE hit list. I would not go so far as to say he had enemies, but he had become the first ethnic politician to embrace national politics. And the speed at which his journey in national politics was taking off, he seemed to be garnering a significant amount of support from the populace and I suppose that may have been a threat to others, whosoever they may have been.

He was a very charismatic individual. He was capable of communicating in all three languages. His versatility was not just in politics but also his knowledge in law, being a President’s Counsel, which was significant. In a branding sense, it was a very appealing package to look up to and even accept as a leader. This could have ruffled feathers, but again, who is to say without evidence in hand?

Q: How do you see the founding of the SLMC in the early 1980s?

My father founded the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress in 1981. He felt at the time many of the politicians who were Muslims were beholden to the majority parties and so when it came to speaking out on minority rights, there was a limit to which they could do so.

At the end of the day, the leadership of those parties would dictate what those limits were, and this was something which he felt had to change. If real solutions were to be found, then the matters that were tough had to be brought out. He felt that an independent political entity would serve the community and the nation best.

Q: Did the SLMC achieve the objectives on which it was founded? Didn’t its split expose a lot of the friction in the community?

While M.H.M. Ashraff was alive, there was a firm hand that guided the direction of the party. There were those who did not quite agree with the stand of the SLMC. The SLMC always propagated the view that they represented the rights of all Muslims in Sri Lanka. Whilst that view was propagated, it was fuelled by its strength in the north and east.

We had representation in the Western and Central Province, etc. but certainly not as profound as these two regions. There were those who said in the WP, etc., ‘We have no problems here. Why do you want to impede us with these radical views?’ A response at the time if I recall right was, ‘You don’t have a problem now, but a time will come when you will have a problem and then you will need this entity.’

We didn’t think it would happen 40 years later, but it did. We didn’t have terrorism, but we find ourselves in a state where we face extremism. Unfortunately, extremism and racism have become part and parcel of society today, which is tragic.

One thing my father was very keen on was that the community be looked upon with a greater measure of respect. That we too have a key role to play in the political discourse of the country as Sri Lankans and not be looked upon as another minority community. That thinking is what eventually led him to conceptualising a political party that subsequently came to be known as the National Unity Alliance (NUA).

Q: What do you see as challenges for Sri Lankans Muslims, especially in the light of the Easter attacks as well as rise in anti-Muslim sentiments in India and many other countries?

Challenge would be an understatement. The first order of the business is to continue to have a stringent process of self-reflection. Yes, there are issues that are pertinent to all communities, but we need to address issues within our own communities.

Are we conducting ourselves in a manner that is acceptable to all? That is not to say we should go about compromising on our traditional values or own religious beliefs. There is something called being mindful of the sentiments of the others and conducting your affairs in such a manner that it doesn’t upset others. It is basic common courtesy, if you think about it.

Q: It is a delicate balance, isn’t it?

Yes, there are insecurities all around. I feel dialogue is best, but you can’t have dialogue fuelled by intimidation. You cannot have this overbearing ‘I have greater rights than you’ attitude. If you want to win the confidence of another, you should first be able to instil a significant degree of confidence in the other that this is a level playing field. Your rights are equal to mine and my right is equal to you and I hold no exclusive privileges that you are not allowed to indulge in. So, let us talk, as human beings, one to one.

How do you go about it? I think the instruction must come down from the political leadership in this country. They have to set an example for the rank and file to follow. It is not something we are seeing every day. I think it would be tragic if we allow the country to continue this manner. It is ironic that regional powers see the potential of Sri Lanka and can understand how far Sri Lanka can go ahead and prosper, but we ourselves as Sri Lankans do not appear to recognise this… Potential that lies not in isolation, but through integration and cooperation, with fellow Sri Lankans. There is a boundless future for us, and it is something we should start building on.

Q: How can intercommunity relations be strengthened in the face of rising tensions?

I remember the immediate weeks and months after the Easter Sunday attacks, the number for calls I received from my friends, some of whom I consider part of my family, asking, ‘Do you guys really feel this way? Is this what you really want?’ I had to explain for hours, speaking to them, reassuring them that this was the action of a terrorist group and the Muslim community does not feel this way.

Now I come back to my point of self-reflection. Speaking as an individual, my life in Sri Lanka, the way I grew up, the way I was raised, we lived as what we like to term ‘traditional Muslims’. We had a certain way of life, our practices, our spiritual beliefs that have not changed, and I doubt if they will ever change. But there have been drastic changes in the community because of external influences.

What we have been debating in the community, what we say to ourselves is, it is one thing to want to practice whatever that practice may be yourself, but it is another thing to walk into another’s home and say ‘you will go to hell if you do not abide by these new practices’.

Religion is an extremely personal matter between you and your makers. I think as Muslims it would be good for us to reflect on how we conduct ourselves, publicly and privately, and how we move with the other communities in the country. There has to be a significantly more strenuous effort to integrate with the rest of society. You can profess to be a fully-fledged Sri Lankan and still retain your cultural beliefs and preserve your traditional practices. Never by compromising but we need to make an effort and be willing to do that.

Q: How do you see the role of education in building intercommunal relations?

One should make every effort in one’s power to make a child trilingual. How can you say one is a grounded Sri Lankan if you do not have mastery of all three languages? It would be ideal if we have a link language that works for all. Education is the solution to all our problems. That is the hardest to change but if we can achieve it, I believe we are on a very firm footing.

When you look at the way that technology is developing, there are individuals who are advocating archaic policies for education, not realising that if you educate your children on those lines, they are never going to be able to bridge the gap at the rate that technology is developing. They are doing more damage than good.

Q: Your views on living in and acceptance of a Sinhala Buddhist country?

The acceptance has always been there. I grew up always knowing this is a Sinhala Buddhist country. Ideally speaking, you and I might have different points of view, but the fact of the matter is that this is a Sinhala Buddhist country and I have never been threatened by that. I think the problem arises when having a conversation and, in order to win an argument, that is put forward. That is when you go wrong. If you want to win an argument, you win on the merits of the case. You do not win the case by saying ‘this is a Sinhala Buddhist country, so it has to be this way’. That is intimidation.

Broadly speaking, I am immensely proud that there is Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa and Sigiriya. When I have a friend coming down from abroad, I plan their trip from the Temple of the Tooth to all these places. As someone who is in the communication industry, I know so many people from the minority communities who would gladly propagate from a tourism perspective, that Sri Lanka being a Buddhist nation, Buddhist tourism.

That being said, when you speak about the business of talking about a Sinhala Buddhist nation, don’t use that statement to threaten or intimidate others because that causes an instant backlash. And the moment that backlash happens, whatever chance you have of reaching an amicable settlement is gone.

Q: How do you see the role of the political leadership in all this and our failure to build a Sri Lankan identity?

As Sri Lankans, when was the last time we were inspired? When I say inspired, I mean not by an election victory or a vote in Parliament or a Court ruling, but when we looked at someone not as a politician but as a statesman who represented the country with such dignity, such poise, such finesse.

When was the last time we looked at the person and said, ‘I am so proud that person is a Sri Lankan?’ [Late Foreign Minister] Lakshman Kadirgamar was the last. He was beloved by all Sri Lankans. When are we going to get another Lakshman Kadirgamar? That is what we must aspire to.

I will never forget the statement the late Kadirgamar made to the effect ‘I am first Sri Lankan, second a Tamil’. That is the same for me. I am Sri Lankan by birth. My religion comes in after my birth. I was born in this nation of Sri Lanka. When are we going to have a political individual who is going to be able to inspire the people of this country to think along those lines without hammering it down our throats or intimidating us into following that path or threatening us to follow that path and win the hearts and minds of all people?

I want my child to experience this country the way I experienced this country. The love I have for this country is not by going to fancy places in Colombo, I have walked on the beaches with fishermen, had ‘kahata’ with hakuru at the village kiosk, had conversations with people. That is the real Sri Lanka.

Q: Are you optimistic for the future?

I have always been an optimist, although I have been burnt many times. I have always believed in the potential of the people. I have seen the good in people as opposed to the bad. You cannot stop believing. If the cream of what we have as talent in every discipline decides to bail out, the country is never going to go forward.

We have a generation that is looking up to us to lead the way and we have a responsibility and I am glad to see many of my friends, who are in excellent positions, are leading. We need to be able to take every effort within our own sectors and see how we can build a better society for our people. It is not political. It is more a moral obligation on all of us Sri Lankans that we need to inculcate in each other.

Q: Do you see a future role in politics for yourself?

I can say I have been in politics from the day I was born because I was born to a political family. I grew up in a house where politicians, be it ministers, MPs or provincial councillors, were regular at the lunch table. It was the norm for me. Something I picked up from my father is that you do not have to be in politics to be able to contribute to society and that is something I have been doing to this day. I am not cut off from politics. Am I engaged in active politics? That I have placed in God’s hands.