Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 3 April 2019 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Radhika Coomaraswamy

I recently attended an event organised by the Walpola Rahula Institute. In just a few years Ven. Galkande Dhammananda Thero has created a safe space where Buddhists, women and minorities can have a discussion about the important ideas of our time and the best way forward for reconciliation.

Venerable Dhammananda Thero has no strong view that he imposes on others but he is a facilitator for frank exchange and dialogue, an enabler who makes you feel secure and cared for no matter who you are. When you are with him you have a strong sense of compassion and belonging.

|

Ven. Galkande Dhammananda |

|

Prof. Asanga Tilakratne |

The occasion for the get together by the Institute was the release of the English translation of Ven. Walpola Rahula’s book ‘Sathyodaya,’ translated initially by Padma Gunasekara. Niranjan Selvadurai translated the final version. Ven. Walpola Rahula, a Buddhist legend, was, as we all know, a graduate of the University of Colombo, University of London and the Sorbonne and was a Professor of History and Religion at North Western University. He was the first Buddhist monk to enter university and first one to be a professor in a prestigious university outside Sri Lanka. He was also once the Vice-Chancellor of Vidyodaya and the Chancellor of Kelaniya University. ‘Sathyodaya’ was his first book but he went on to write many definitive works including ‘What the Buddha Taught,’ which is his most famous work.

Critique of mindless rituals

The speakers at the event put forward many ideas from the text of ‘Sathyodaya’ that are relevant for our times and are valid across all the religions. Much of ‘Sathyodaya’ is a critique of mindless rituals, especially offerings of food and medicine to statues when there are so many poor, underprivileged people in our country.

Dr. Prabha Manurathna from the Department of English at Kelaniya quoted from ‘Sathyodaya’ and made the audience realise the moral unacceptability of all these actions, especially when they are done in excess. According to Dr. Manurathna, within the Buddhist world of explanation such offerings do not reflect an understanding of his teachings and when the material offerings are so excessive as to be grotesque, they actually impact the society.

Born into the Hindu religion I can also totally identify with Ven. Rahula’s words and Dr. Manurathna’s approach. Ven. Rahula stated in ‘Sathyodaya’ that all this excessive offering of material things to Buddha images was a sign of “low moral maturity” and he urged that all such material things should be given to the poor and that would be a proper and worthy way of honouring the Buddha.

Dr. Sunil Wijesiriwardena, though, had an interesting analysis of this whole debate. He argued that when a person cooks a meal and gives the first portion to the Buddha, or when a simple lamp is lit there is something beautiful in these gestures. They evoke a sense of the sacred that is also important in the spiritual life of many people.

One could argue that much of art is focused on the symbolism of these small gestures, a common language for the community of believers. It is the excess, the pomp and artificial ceremony when resources can be better used that cuts against the grain of radical thinkers like Ven. Rahula. The genuine gestures of beauty and spirituality would be exempt but where excessive material offerings are substitutes for moral rectitude, there is a serious problem.

Rationalism and logical positivism in Buddhist thought

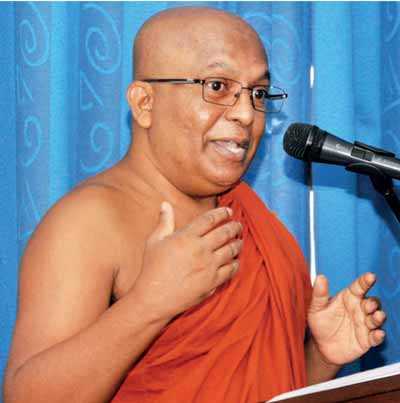

The written style of ‘Sathyodaya’ compelled Professor Asanga Tilakaratne, the keynote speaker, to address the question of rationalism and logical positivism in Buddhist thought. One could argue that most of the world’s religions do not give the rational thought process as much emphasis as does Buddhism.

Hinduism, especially in its Bhakti form, and Sufism in its manifest form rely on a mystical union with the divine. Rationality is not part of the immediate religious process though some Hindus point to the Vedantic texts as their rational structure. Even Christianity and Islam in their initial texts were “revelations” though later theologians like Saint Thomas Aquinas argued that God was reason and rational thought was his gift. It is the dominant view that Buddhism from the very onset valued a rational thought process, drawing on logic and reason.

Professor Gananath Obeyesekere in his extraordinary work, ‘The Awakened Ones,’ argues, on the other hand, that the Buddha like many other poets and religious leaders was a visionary, and that the visionary experience was different to the rational process. Comparing the visionary experiences of the Buddha, William Blake and people like Blavatsky he argues for a more holistic understanding of Buddhism and the Buddha’s thought processes.

The Buddha’s thoughts come, not only from the rational thought process, but also from the part of our imagination from where poetry and the creative forces flow. Drawing on thinker such as Nietzsche and Freud he points to the neglected analysis of our psyche due to the tropes of the western Enlightenment, an analysis that will make us better understand the genius of people that came before us.

Nevertheless as Professor Asanga Tilakaratne makes clear, for most of the world, traditional Buddhism – as opposed to heterodox Buddhism – has a rational and logical structure that cuts away myths, legends and superstitions.

Drawing parallels with western rationalist thinkers, Prof. Tilekaratna’s comparison of Buddhism with thinkers from Kant to Wittgenstein was a very thought-provoking one. Dr. Sunil Wijesiriwardene seemed to be less comfortable with this comparison. Like Professor Gananath Obeyesekere he saw Buddhist rationalism from a completely different perspective with a different ontological worldview. Can reason have many forms? Can Buddhist  rationalism manifest reason in a different way? These are some of the thoughts that the speakers evoked with their interesting analysis.

rationalism manifest reason in a different way? These are some of the thoughts that the speakers evoked with their interesting analysis.

Caste and religion

Another topic discussed at length in ‘Sathyodaya’ came to the fore in the discussions because it particularly irked Ven. Rahula and is very relevant to our times. This is the issue of caste and religion.

The Hindu religion to which I was born aims at equality in its mystical practices, but in social life caste continues to play a dominant role. Caste defines the spaces we can walk in, the temples where we can be comfortable and the eating places where we can feel free.

The speakers spoke of caste and the practices of Buddhism. Examples were given of practices of caste-based discrimination in certain Buddhist structures and events. Ven. Rahula’s book ‘Sathyodaya’ has a very clear, a message that in the early part of the 21st century should apply to all religions.

Putting forward the stories of Suneetha, the street sweeper and Upali the barber who were ordained by the Buddha regardless of their origins, he argues, “there is no place for caste based segregation within the teachings of the Buddha” or we should add anywhere in real life.

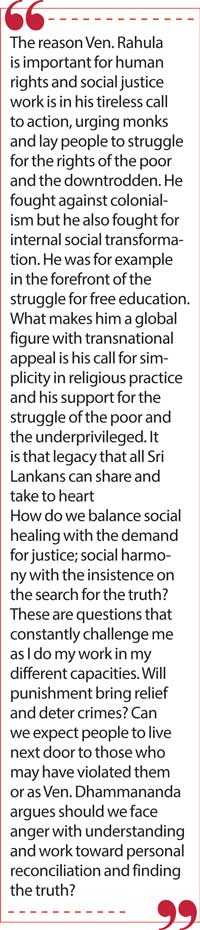

Tireless call to action

The reason Ven. Rahula is important for human rights and social justice work is in his tireless call to action, urging monks and lay people to struggle for the rights of the poor and the downtrodden. He fought against colonialism but he also fought for internal social transformation. He was for example in the forefront of the struggle for free education.

Some people may read his radical Vidyalankara student days when ‘Sathyodaya’ was written as a call to extreme nationalism and many monks have taken that trajectory. But, what makes him a global figure with transnational appeal is his call for simplicity in religious practice and his support for the struggle of the poor and the underprivileged. It is that legacy that all Sri Lankans can share and take to heart.

Winning without creating a loser

In a beautiful passage in his introduction to the book, Ven. Galkande Dhammananda Thero writes, “the Buddhist focus should be on winning without creating a loser. Any victory gained by producing a loser or an accused will be incomplete and temporary.”

Many researchers also find that in certain Buddhist areas, Buddhist feelings of social harmony and healing go against the grain of punishing people. The Buddha, according to all accounts, was totally against demonising people and making them “the other” whether they are soldier or civilian.

Yet memories of my experience on the Youth Commission in the 1990s pointed in a different direction. The young men I met repeated the word “Asardharanaya” over and over again and there was sheer rage in their eyes. Similarly when I meet women who have suffered terrible violations or watched their children “disappear,” whether in Sri Lanka or any other country, compassion and understanding makes it difficult to insist that they forgive.

How do we balance social healing with the demand for justice; social harmony with the insistence on the search for the truth? These are questions that constantly challenge me as I do my work in my different capacities. Will punishment bring relief and deter crimes? Can we expect people to live next door to those who may have violated them or as Ven. Dhammananda argues should we face anger with understanding and work toward personal reconciliation and finding the truth?

It is the discord we must address

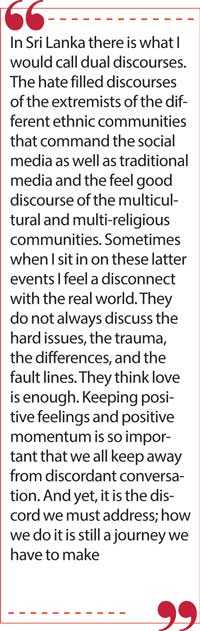

In the 40 years of my professional life, I have been to many multi religious and multicultural forums and event. In Sri Lanka there is what I would call dual discourses. The hate filled discourses of the extremists of the different ethnic communities that command the social media as well as traditional media and the feel good discourse of the multicultural and multi-religious communities.

Sometimes when I sit in on these latter events I feel a disconnect with the real world. They do not always discuss the hard issues, the trauma, the differences, and the fault lines. They think love is enough. Keeping positive feelings and positive momentum is so important that we all keep away from discordant conversation. And yet, it is the discord we must address; how we do it is still a journey we have to make.

I therefore want to thank the Walpola Rahula Institute for creating the safe space so we can discuss all these issues with honesty and compassion under the guidance of Venerable Galkande Dhammanandha Thero.

Instead of screaming and silencing each other, these are the conversations we must have in dignity and safety. Conversations on what divides us; ethnicity, class, caste, gender and disability. Conversations on social justice and social harmony, conversations about the war and the peace that has followed, conversation about the contours of justice and healing, conversations about the terrible malaise that ails our young people and makes so many of them despair.

These conversations can then be the building blocks for the compassion, understanding and sustainable peace that Ven. Dhammananda Thero has spoken so much about. To reach out, utter the difficult words and listen to the answer is the only way for us to move forward.

Pix by Shehan Gunasekara