Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Saturday, 28 March 2020 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Kithmina Hewage

By Kithmina Hewage

Over a quarter of the world’s population is currently under movement restrictions. For the first time in recent human history, coronavirus has shattered the myth that the economy must come first.

While public health concerns, undoubtedly, should take precedence over all other considerations when dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, it would be unwise to ignore the economic costs of the current situation. Reviving an economy where production grinds to a halt in a hitherto unprecedented manner is not an easy task, and if not done properly, will lead to further damage.

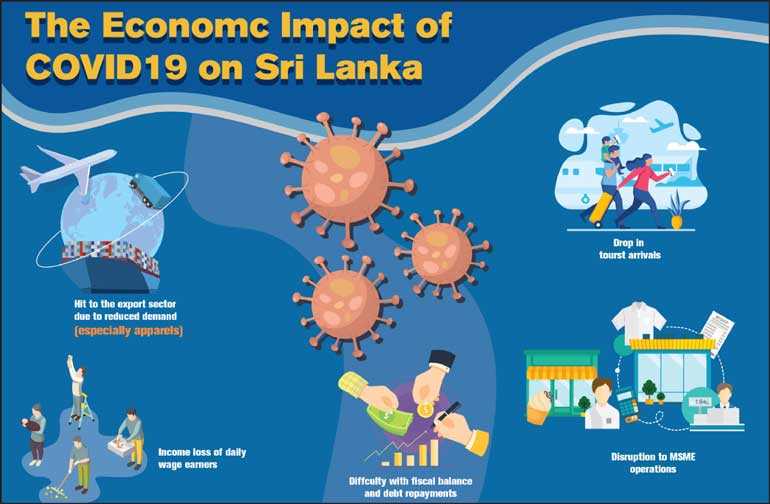

Small economies such as Sri Lanka, in particular, whose economic backbone is made up of micro, small, and medium sized enterprises (MSMEs), dependent on export revenue for foreign currency generation, and is simultaneously managing a critical debt and fiscal crisis, are going to be particularly vulnerable.

This blog provides an overview of the economic impacts of COVID-19 on the Sri Lankan economy and explores potential measures that could be taken in the short and medium to long run.

The big picture: Impending global recession

The economic implications of COVID-19 are unprecedented. The most recent pandemic that spread to this extent was the Spanish Flu in 1918. The nature of economics currently, however, is vastly different from a century ago. Economies are much more interlinked with each other through supply chains, migration, and vast volumes of international trade. As a result, countries are much more vulnerable to external shocks now than ever before.

Under such circumstances, the economic implications of COVID-19 on Sri Lanka, hinge not only on the situation within the country, but also on critical markets such as the United States, Europe, and China. It may well be that the world is yet to experience the worst of the pandemic, and the global economy will see further significant turmoil in the months to come.

Under such circumstances, the economic implications of COVID-19 on Sri Lanka, hinge not only on the situation within the country, but also on critical markets such as the United States, Europe, and China. It may well be that the world is yet to experience the worst of the pandemic, and the global economy will see further significant turmoil in the months to come.

Most recessions are caused by a (i) demand shock (e.g. post 9/11 downturn), (ii) supply shock (e.g. OPEC oil embargo in 1973), or (iii) financial shock (e.g. Great Recession in 2008). Covid-19 promises to cause all of them in one blow. As entire populations move into lockdown, and consumer demand falls drastically, the demand shock is clear. Some initial data suggests that global GDP may have fallen by as much as 5% during the first quarter of 2020.

Similarly, as noted earlier, supply chains around the world have been severely disrupted, creating supply shocks. Even as China restarts its economic activities, the situation in Europe and US will likely cause continued disruptions in the supply chain.

Finally, amidst a push by governments to pass stimulus packages, MSMEs that work on small margins and very little reserve cash are likely to face a liquidity crunch, leading to foreclosures and bankruptcy. The US Federal Reserve has already injected $ 500 billion into the repo market, which suggests that there are concerns regarding an impending financial shock. As such, an imminent global recession is inevitable.

This situation has to be managed as a public health crisis. Countries should be careful not to move too fast in trying to ease restrictions on social distancing measures to restart the economy without realistically containing the likelihood of the virus spreading again. China is currently attempting to approach this delicate balance, but Sri Lanka is not close to that point yet. Failure to contain the possibility of community spread before easing restrictions will only lead to a catastrophic burden on the national health system and will inevitably lead to greater economic losses

High risk of unemployment in the Sri Lankan export sector

A global recession is likely to significantly reduce the demand for Sri Lanka’s exports, and lead to considerable job losses. During the Great Recession from 2008 to 2010, an estimated 90,000 Sri Lankans lost their jobs due to downsizing amongst manufacturing firms, especially in the apparel sector. Sri Lanka is also susceptible to delays in accessing raw materials for manufacturing from China.

Moreover China’s economic slowdown could severely inhibit a major source of foreign direct investment (FDI) to the economy. In fact, in a recent research paper by the Overseas Development Institute (ODI), Sri Lanka was identified as one of the most vulnerable middle-income countries due to the impacts of COVID-19 and a resulting Chinese economic slowdown.

In more bad news, the current crisis will gravely affect the tourism sector. In January and February alone, tourist arrivals to Sri Lanka fell by 6.5% and 17.7% respectively, compared to 2019. The closing of the Sri Lankan border for foreign passenger arrivals in mid-March, combined with global travel restrictions, will undoubtedly lead to further losses.

Combined with the loss of revenue last year following the Easter Sunday attacks, the drop in global travel will lead to further job losses both in the formal tourism sector as well as ancillary informal services.

Moreover, unlike the Great Recession and other recent external shocks, both developing and developed countries are likely to face significant economic downturns during the pandemic. Therefore, given the scale and cross-sectoral nature of the crisis, its economic impact is assumed to be greater than during the 2008 financial crisis.

Even more worryingly, unlike in 2009, there does not appear to be a coordinated global response to minimise the effects of a global recession.

Social distancing, curfews, and the domestic economy

Meanwhile, enforcing the necessary social distancing measures, and subsequently, curfews have effectively stalled the local economy. Whilst some economic activities that can be carried out remotely continue, particularly in the services sector, manufacturing and retail services have effectively come to a standstill.

Moreover, even though the Government has allowed agricultural production to continue unhindered, uncertainties surrounding temporary lifting of curfew hours and means of distributing essential goods to households result in wastage and a slowdown in the supply and storage of perishable agricultural goods.

Whilst many will feel the economic hardships, the exact short-term impact is difficult to estimate just yet. Daily wage earners and MSMEs, including those in the informal sector, are going to be disproportionately affected during the current crisis. MSMEs account for 52% of total GDP and 45% of national employment.

Meanwhile, nearly a half of the population is employed in the non-agricultural informal sector. Therefore, the absence of any meaningful economic activity for an entire month, and possibly longer, will severely affect the wellbeing of those involved.

Since many MSMEs operate on thin margins and low levels of reserve savings, a prolonged lockdown without adequate support would lead to unemployment and foreclosures, with few surviving until the resumption of economic activities.

Policy solutions unlike any other

As noted earlier, the public health considerations and the economic stakes of the current situation are unprecedented. Therefore, the Government should be open to unique policy solutions to address a unique crisis. Thus far, the Government has taken several measures to ease the burden on the public with an emphasis on low-income households. During the past week alone, the Central Bank has announced additional liquidity measures and downward adjustments to policy interest rates, the Government has issued debt moratoriums for SMEs in identified vulnerable sectors such as tourism and construction, debt moratoriums to the self-employed, relief on personal loans and credit card payments, and reduced the prices of some essential goods, to name a few. Further measures may be introduced.

The Government has also requested debt-relief, in the form of suspending debt repayments for a time period, from its lenders in an effort to gain greater flexibility to address the current crisis. These measures have created some breathing space by easing up an element of financial constraints for firms and workers, and crucially injecting a measure of liquidity into the economy.

That said, these measures do not necessarily create a swift cash flow into the hands of vulnerable groups such as daily wage earners and most MSMEs, especially those in the informal sector. Therefore, a mechanism to provide cash flows will be needed, in addition to policies such as price reductions, since the continuation of curfew or a lockdown would severely constrain disposable income amongst these groups and heighten difficulties in accessing basic essentials.

The broader challenge for the Government, however, will be to design an effective fiscal response that allows businesses to sustain themselves through this period and minimise job losses, whilst simultaneously managing a constrained fiscal landscape.

The high level of Government expenditure required for such stimulus packages, alongside an approximately Rs. 650 billion revenue loss due to tax cuts introduced following the Presidential Election last year, as well as delays in revenue collection during this crisis will all create a significant fiscal burden. An economic relief package may not help all small businesses, but will at least reduce the potential for a cascade of small business defaults, high rates of unemployment, and a resulting domestic financial crisis.

Importantly, this situation has to be managed as a public health crisis. Countries should be careful not to move too fast in trying to ease restrictions on social distancing measures to restart the economy without realistically containing the likelihood of the virus spreading again.

China is currently attempting to approach this delicate balance, but Sri Lanka is not close to that point yet. Failure to contain the possibility of community spread before easing restrictions will only lead to a catastrophic burden on the national health system and will inevitably lead to greater economic losses.

This is unchartered territory for all, and uncertainty regarding the pandemic as well as global and domestic economic effects will pervade all policies made at least during the next six months.

However, it is in Sri Lanka’s best interests to prepare for the future and enact proactive policy measures to mitigate potential economic costs as much as possible.

[Kithmina Hewage is a Research Economist at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To talk to the authors, email [email protected]. To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ – http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/]