Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Tuesday, 1 December 2015 00:50 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

COP 21 Climate Summit in Paris draws largest-ever gathering of world leaders

President Maithripala Sirisena yesterday called for speedy action on climate change in his address at the 21st session of the Conference of the Parties and the 11th session of the Conference of the Parties serving as the Meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol (COP 21/CMP 11) in Paris.

He urged the world leaders to seize the unique opportunity in Paris Summit to create a turning point by recognizing our universal responsibility to protect and safeguard our fragile planet for the benefit of all living beings.

Addressing the United Nations Conference on Climate Change – 2015 in Paris, he asked them to “decide on ways to secure our only common home, this fragile Planet that we call Earth, for our future generations.”

Describing the impact of Climate Change threatens our very survival, he said that in Sri Lanka, the adverse impacts are already obvious.

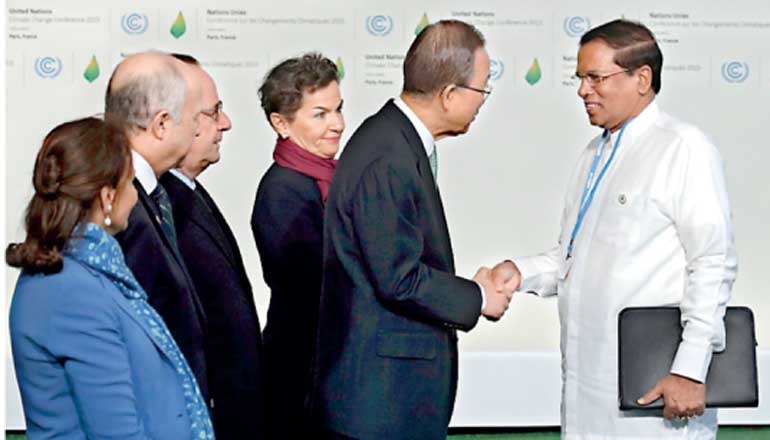

United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, accompanied by French Ecology Minister Segolene Royal (L), French Foreign Affairs Laurent Fabius (2ndL) and French President Francois Hollande (3rdL), welcomes Sri President Maithripala Sirisena as he arrives for the opening day of the World Climate Change Conference 2015 (COP21) at Le Bourget, near Paris, France – Reuters

“Domestically, we have developed a ‘National Climate Change Policy’ and prepared a ‘National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy’. To implement these strategies, Sri Lanka’s requirements could be approximated at around $ 500 million,” the President said.

Sirisena flew into Paris from Malta at dawn on Sunday to join world leaders at what is considered to be the largest-ever gathering of world leaders in Paris, skipping the ceremonial closing ceremony of CHOGM Malta, in order to be on time for the Climate Summit to address the summit as one of the preliminary list of speakers that included leaders who have registered to deliver a statement at the Leaders Event yesterday.

Due to the number of leaders attending, two meeting rooms were made available for delivery of the statements. In addition, the list was divided into two segments, morning and afternoon and President Maithripala Sirisena got slotted into the afternoon speakers.

Given the number of parties and the limited amount of time available for statements, it was necessary to limit the duration of each statement to a strictly enforced three-minutetime allocation.

The summit is seen as the strongest-ever push for a global agreement on climate change, leaders and monarchs from nearly 150 countries will assembled under one roof here, hoping that the show of solidarity would force a different result from the one six years ago when they last gathered in such numbers for the same cause.

Unprecedented security measure naturally taken by Paris in the aftermath of the Paris attacks required strict restrictions on entry to the conference location. Special badges were required for access and attendance at the opening of COP 21/CMP 11 and the leaders event and to hear statements by heads of state/governments.

Heads of states and governments pose for a family photo during the opening day of the World Climate Change Conference 2015 (COP21) at Le Bourget, near Paris, France – REUTERS

Battling climate change

French President Francois Hollande made an unexpected appearance at the Commonwealth summit in Malta — France is not part of the Commonwealth — and likened the problem of climate change to the battle against terrorism.

“Man is the worst enemy of man. We can say it with terrorism but we can say the same when it comes to climate. Human beings are betraying nature, damaging the environment. It is therefore up to human beings to face up to their responsibilities,” he said.

The French President reiterated the commitment to the holding of the COP21 at the Malta Climate Session Press conference held as a prelude to the Summit at which all of us members of the international media covering CHOGM was present. Almost all of the CHOGM international media have flown direct from Malta to Paris to cover the COP 12 Summit.

To call off such a major gathering of world leaders in the French capital would have been an unthinkable surrender to terrorism although that was a constant question posed to the French President and the United Nations Secretary General recently in the run up to the summit.

The world leaders have come together here to show solidarity in the call for climate change in an environment where their security concerns areat its zenith. The United Nation’s Secretary General called on the Commonwealth leaders at CHOGM personally two days ago and at the press conference held in Malta calling on the leaders to gather in Paris, stating that terrorism cannot deter holding the summit, which has been met with much admiration and positive result.

“I think that all the stars seem to be aligning (for an agreement),” UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon said in Malta on Friday during the Commonwealth summit. “There is a strong commitment not only from the Government but also from the business communities and civil society... We are going to make it happen and the time for taking action is now. We cannot again delay or postpone it until tomorrow,” he said.

Ambitious attempt

World leaders thus launched an ambitious attempt to hold back the earth’s rising temperatures, urging each other to find common cause in two weeks of bargaining meant to steer the global economy away from dependence on fossil fuels.

They arrived at United Nations climate change talks in Paris yesterday armed with promises and accompanied by high expectations. After decades of struggling negotiations marked by the failure of a previous summit in Copenhagen six years ago, some form of landmark agreement appears all but assured by mid-December.

Warnings from climate scientists, demands from activists and exhortations from religious leaders like Pope Francis, coupled with major advances in cleaner energy sources like solar power, have all added to pressure to cut the carbon emissions held responsible for warming.

Most scientists say failure to agree on strong measures in Paris would doom the world to ever-hotter average temperatures, bringing with them deadlier storms, more frequent droughts and rising sea levels as polar ice caps melt.

Facing such alarming projections, the leaders of more than 150 countries responsible for about 90% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions have come bearing pledges to reduce their national carbon output, though by different degrees.

Achieving an international agreement committing both rich and developing nations to the fight against global warming would mean “we can have confidence that we’re doing right by future generations,” US President Barack Obama said earlier this month.

“No Planet B”

On the eve of the summit, hundreds of thousands of people from Australia to Paraguay joined the biggest day of climate change activism in history, telling world leaders there was “No Planet B” in the fight against global warming.

Meanwhile, French police detained scores of protesters after violent clashes in the center of Paris. The police fired tear gas to disperse about 200 protesters, some of them masked, who responded by hurling rocks and candles at them.

Those who have been following the Summits will remember similar, though relatively smaller, gathering of political leaders were witnessed in Copenhagen in 2009, the last time the world took a shot at finalising a climate agreement.

At that time, presidents and prime ministers from over 110 countries had flown in on the last two days of the conference in a desperate bid to clinch a deal. But all they could manage was a face-saver in the form of a “political declaration”.

Excitementand expectation

The situation is different now. The excitement and expectation, both sky-high in Copenhagen, have been tempered and a lot of background work has been completed in the last couple of years.

But the most important difference is in the nature of the agreement being negotiated.

In Copenhagen, the world was trying to finalise an agreement that would have assigned specific emission reduction targets to some countries, while telling everyone else what to do. The agreement being looked forward to in Paris would allow every country to do what they think they can.

While Copenhagen was aiming to deliver a comprehensive legally-binding treaty, Paris hopes to put together a framework agreement with just enough muscle and bone to stand on its own — for now. The agreement under negotiation is set to become operational only in 2020, in time to take over from the Kyoto Protocol.

Contentious issues

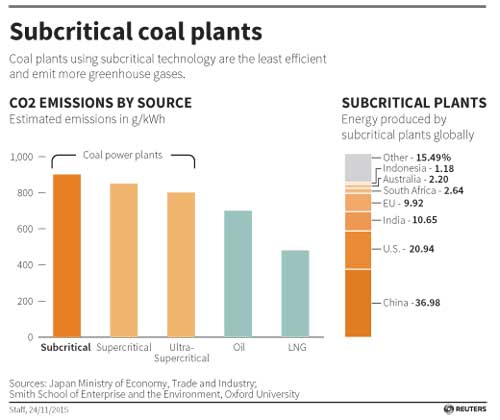

But, while the bar for success in Paris is quite low, there is no dearth of contentious issues. Now that emission reduction targets — which country should reduce its emissions by what amount — are to be decided by the countries themselves, the biggest fights are likely to be over money, and technology.

Developed countries, which account for the overwhelming amount of accumulated greenhouse gases in the atmosphere over the last 150 years, are mandated to provide money to the developing and least developed nations to help them adapt to the impacts of climate change, and also to shift to low-carbon growth trajectory. They are also mandated to transfer climate-friendly technologies to the developing world.

Developed countries, which account for the overwhelming amount of accumulated greenhouse gases in the atmosphere over the last 150 years, are mandated to provide money to the developing and least developed nations to help them adapt to the impacts of climate change, and also to shift to low-carbon growth trajectory. They are also mandated to transfer climate-friendly technologies to the developing world.

In Copenhagen, the developed countries had promised to collectively “mobilise” $100 billion in “new and additional” assistance every year from 2020 that can be channelised to developing countries as climate finance. Later, they also promised to raise $10 billion for a four-year period before 2020. But developing countries, including India, have often accused the developed world of using “dubious methods” to show progress on these commitments.

The developing countries are pressing for the finalisation of a financial architecture that will ensure the flow of “new”, “adequate” and “predictable” funding towards them. They also want a commitment from the developed world that the $100 billion purse would be progressively made bigger post-2020.

A similar fight is likely over climate-friendly technologies, as well. Developing countries want access to technologies protected by intellectual property rights but at low costs. India, for example, has listed around 20 indicative technologies that it requires for adaptation and low-carbon economic growth.

There are major differences over other issues as well, like how to assess whether everyone is acting to the best of their ability, or how to compensate the gap between the actions that countries are taking and those required to stall climate change.

A personal mission

Many world leaders assembling in Paris have made a climate agreement their personal mission. US President Barack Obama, one of the few leaders who was present in Copenhagen as well, sees the agreement as one of the possible legacies of his presidency. For German chancellor Angela Merkel, another leader who was present in Copenhagen, a successful climate agreement will strengthen her leadership within the European Union. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been talking bold and ambitious on climate change, and keen to present India as a solution provider. Canada’s newly elected Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, too, has made all the right noises on climate change during his campaign trail. On Friday, Canada announced it would provide 2.65 billion Canadian dollars to the developing countries in climate finance over the next five years, double of what the previous government had promised. But it is the French who probably would be the most satisfied to see a successful outcome in Paris which is hosting the conference less than a month after it was attacked by terrorists. Why the deal is believed to be within reach is that like Copenhagen 2009, Paris aims to cut deal on emission of greenhouse gases. But unlike failed push for binding deal in 2009, Paris will let nations chart their own course.

(The writer is a special correspondent for the Daily FT and also accredited as a member of the President’s official media delegation in Paris.)