Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Friday, 11 December 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

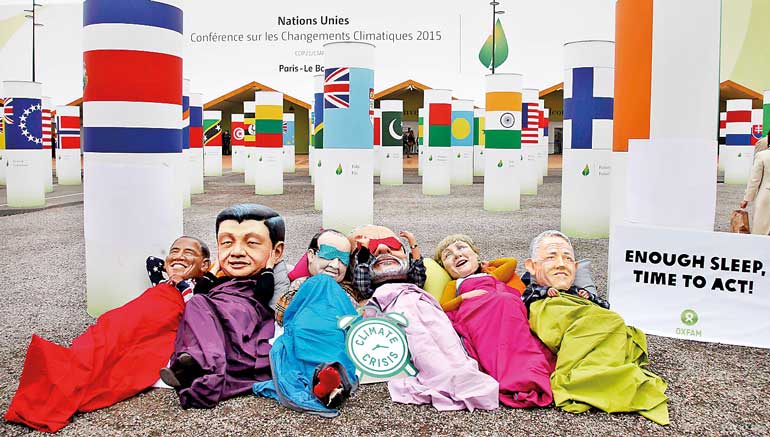

Activists of global anti-poverty charity Oxfam wearing masks depicting some of the world leaders U.S. President Barack Obama, Chinese President Xi Jinping, French President Francois Hollande, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, and Australia’s Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull stage a protest outside the venue of the World Climate Change Conference 2015 (COP21) in Le Bourget, near Paris, France, December 10, 2015. REUTERS

The facade of the cimate change Summit

By Charnika Imbulana in Paris

The COP 21 Paris Climate Change Summit has come to its last day. Everyone’s hope is that today, 11h December 2015, with the culmination of the official final day of negotiations and upon Saturday’s release of the newly honed draft text on the climate change agreement, the world’s top climate negotiators would clinch the deal.

Progress, they say, has been made. But significant challenges remain, with the agreement still riddled with contentious issues even until yesterday, with the deadline looming large with barely hours to go, today.

After nearly two weeks of UN talks here in Paris, a draft text of the agreement that’s meant to save humanity from the dangers of global warming was published on Wednesday. Although, much shorter than a previous version and with less in brackets - indicating disagreement – there action was mixed.

Chinese negotiators were being accused of trying to weaken the new global climate accord when they had attempted to water down efforts to create a common system for the way countries report to the UN on their carbon dioxide emissions and climate change plans.

Ironically, at the same time, Beijing declared its first “red alert” for heavy smog this week, closing schools and curbing car use.

Chinese delegates were reported to be resisting a measure widely seen as crucial for a successful accord: a requirement for countries to update the pledges they have made to limit their emissions, preferably every five years from around 2020.

China wants any updating of the carbon dioxide emissions reduction targets contained in these plans to be voluntary while it is supporting a general stocktaking review of countries’ pledges every five years, one envoy is quoted to have said.

China has been classed as a developing country that has not been obliged to report to the UN on its carbon emissions as regularly as older industrialised nations under rules dating back to 1992.The US and most other developed countries say this situation must be changed in the new Paris climate agreement.

Among the key countries being watched is India whose negotiators want to avoid being tied into an accord that holds back the nation’s growth. They also want to avoid the inclusion of 1.5C.

But India has also formed a Solar Alliance of 120 countries and promised to ramp up renewables to reduce coal usage.

They have opposed wording which includes “developing countries in a position to do so” among those making contributions to climate finance.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, writing in the Financial Times, said that wealthy countries that “powered their way to prosperity on fossil fuel” had a moral duty to lead the fight against climate change. It was regarded as being one of the most divisive issues of the conference on the eve of the two-week meeting,

The Paris Committee, also known as the “climate musketeers” - ministers charged with facilitating compromise when needed created by the French Presidency of COP 21 - reported significant improvement in most areas, and certain clear divisions in some.

Divisions among nations

Among the areas of clear division is how to deal with the issue of differentiation - the differing responsibilities between developed and developing countries, chiefly over finance. Here the ministers reported that “very clear faults lines remained.”

More than 100 countries had come together to push for a truly strong, ambitious agreement. The so called High Ambition Coalition includes 79 African, Caribbean and Pacific countries, the European Union and the United States. Whether or not this broad coalition can succeed in its goal of securing a strong agreement is the question.

The EU has agreed to pay $519m to support climate action until 2020. And the alliance has agreed there must be a transparent mechanism in the text which tracks nations› progress on climate pledges.

Small island-nations want to push for a deal that will limit warming to 1.5C in response to evidence from many scientists that 2C is insufficient.

The problem area of «loss and damage» - how developing countries are compensated for the effects of climate change - is as prickly as ever.

The US says it can be included in the text but there must be no mention of the word compensation.

There is doubtless a new spirit of cooperation and there seem to be an indication for it to be headed for an agreement. But the question now is: How strong and binding will the accord be for its successful implementation?

In 1997, 192 countries signed the Kyoto Protocol, the world’s only legally binding international climate treaty, which extends the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) that commits State Parties to reduce greenhouse gases emissions, based on the premise that (a) global warming exists and (b) man-made CO2 emissions have caused it.

Signing is optional, indicating an intention to ratify the Protocol. Ratification means that a state is legally bound by the provisions of the treaty. For Annex I parties (e.g. a developed country or one with an ‘economy in transition’) this means that it has agreed to cap emissions in accordance with the Protocol.

The protocol initially covered only developing nations, and now covers just the EU, Australia and a handful of other countries that are required to cut emissions by 2020. There’s also a separate, nonbinding declaration that covers voluntary cuts by scores of countries, rich and poor, up to 2020.

The treaty was brought into force effective 16 February 2005 with Russia’s ratification the “55 percent of 1990 carbon dioxide emissions of the Parties included in Annex I” clause was satisfied

Only 54 countries have accepted the extension of the Kyoto protocol. The majority of these countries are small contributors to gas emissions.

The main goal was the reduction of Green-house gas emission to battle climate change. However emissions have continued to rise since the agreement.

Of all emissions, the biggest contributors are large industrialised economies such as the United States, the European Union and China.

Stricter measures were thus called for to battle climate change.

With the new Climate Change agreement that is hoped for today to clinch a deal in Paris at COP 21, it would lead to a decrease in CO2 emissions in the near future.

By doing this, world leaders and scientists hope to minimise the effects human have on climate change, and in turn it is expected that the effects climate change has on humans will be minimised.