Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Monday, 12 November 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Indian Express: Around 10 am on 26 October, the telephone rang at the Colombo residence of Sri Lanka’s then-Opposition leader Mahinda Rajapaksa. On the line was his arch rival, President Maithripala Sirisena. The message was clear: reach the President’s home, it was time to move.

Hours later, Sirisena had ensured that Rajapaksa was sworn in as Prime Minister, replacing his coalition partner Ranil Wickremesinghe. It was the key act in the tense political drama currently playing out in the island nation.

On Friday, Sirisena dissolved Parliament five days before it was to convene for a crucial floor test, with the new ruling coalition still seven to nine seats short of majority in the 225-member House.

With Sri Lanka going to polls on January 5, 2019, The Sunday Express spoke to scores of political leaders, officials, and political observers to piece together the dramatic hours leading up to the crisis and the split, and to identify the key players involved in the churn.

What emerged was an elaborate plan that had been brewing for several months. Sirisena, feeling threatened by Wickremesinghe’s “self-styled decisions without consultation”, spotted an opening in the spectacular victory of Rajapaksa’s party in the local body polls this year.

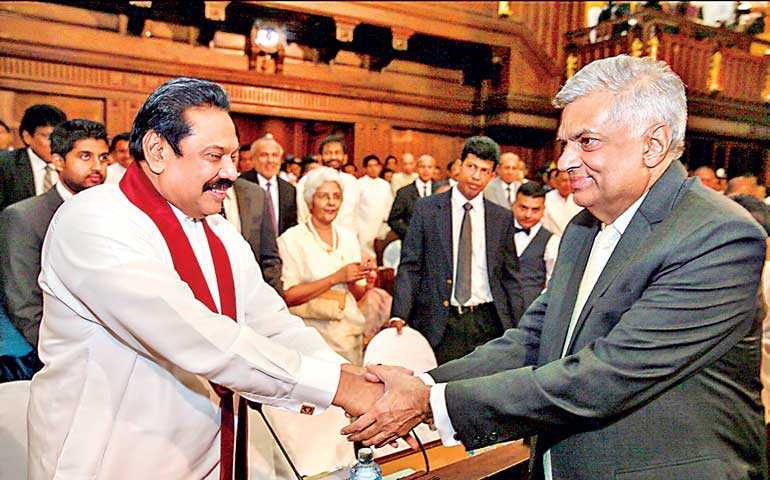

The swift turn of events last month took most of the top leadership in Rajapaksa’s Sri Lanka People’s Party (SLPP) and Wickremesinghe’s United National Party (UNP) by surprise - including Rajapaksa and Wickremesinghe themselves.

“After that phone call, as Rajapaksa’s convoy was getting ready, the venue for the meeting was changed to President Sirisena’s official residence. Again they changed the venue, this time it was the President’s Secretariat in the Old Parliament building. Rajapaksa never expected Sirisena to make such a decisive move that day,” a senior source in the Government told The Sunday Express.

Rajapaksa’s swearing-in as Prime Minister under Sirisena marked a full circle in Sri Lankan politics. Four years ago, Rajapaksa had lost the presidential election to Sirisena following the brutal war that destroyed the LTTE.

How the rift widened

According to multiple sources, it was Sirisena who initiated talks with Rajapaksa, and offered to make him the PM about three months ago. “There were at least four crucial meetings as the talks picked up pace, after Rajapaksa’s brother Basil met Sirisena. But they faced roadblocks whenever Sirisena raised his main condition, that he wants to continue as President,” sources close to Rajapaksa said.

“The government’s declining image was Sirisena’s major concern, while Rajapaksa cited several cases lodged against him and his family to justify the tie-up,” a leader close to Rajapaksa said.

“Depreciation of the Sri Lankan rupee, worsening unemployment, failure to create jobs, and deliver on key promises made in the 2015 elections… President Sirisena was also upset that even a Rs 400-crore project of 15,000 housing units in Colombo hadn’t reached anywhere,” a top official in Sirisena’s office said, listing the “lapses” of Wickremesinghe.

“President Sirisena was being blamed for all the decisions taken by Wickremesinghe,” said Nalaka Godahewa, who headed the Securities Exchange Commission of Sri Lanka and Sri Lanka Tourism in the Rajapaksa regime.

What fuelled the distrust was the perception that Wickremesinghe was close to India. So much so, that last month, the President reportedly alleged in a Cabinet meeting that the Research and Analysis Wing (R&AW) was plotting his assassination. That charge was never substantiated, and Sirisena was quick to publicly distance himself from it, even speaking to Prime Minister Narendra Modi to deny those reports.

A surprise move

Sirisena’s decisive turn took everyone by surprise. “On October 26, we were asked to gather for a meeting in the evening but were not given a reason or agenda,” an MP from Rajapaksa’s party said.

“Even Rajapaksa was not sure of what would happen … He was not well-attired for the swearing-in ceremony except for ensuring that his trademark rust-brown neck scarf was in place. Even his close aides didn’t know; many were sporting casual wear,” sources close to the Rajapaksa family said.

In fact, the sources said, Rajapaksa’s other brother and former defence secretary, Gotabhaya, was to begin a speech at an event organised by a Muslim organisation when he received a call asking him to rush across “for an important meeting”. “By the time Gotabhaya finished his speech, Rajapaksa had become the PM,” sources close to Gotabhaya said.

Sources said Sirisena was waiting for Rajapaksa with a set of legal documents to convince his rival that the tie-up would stand the test of law. “During the meeting, Sirisena was unusually candid, indicating that he had no political future unless he joined hands with Rajapaksa, and delivered on his poll promises of 2015,” said a political leader who was present.

The key players

But that meeting, sources said, would not have been possible without the backing of two key players in the Rajapaksa camp: Basil and Rajapaksa’s former Cabinet colleague S B Dissanayake.

“Basil and Dissanayake worked behind the scenes,” sources said. After Wickremesinghe was removed and the scramble to garner the support of more MPs began, Rajapaksa’s son, 31-year-old Namal, became the public face, meeting the media and issuing statements.

“Namal’s residence and office on Torrington Avenue in Colombo became the nerve centre of all the political games,” sources in the Rajapaksa camp said.

Speaking to The Sunday Express, Namal dismissed criticism that the ouster of Wickremesinghe was against the Constitution. “Well, Wickremesinghe did the same thing in the past. President Sirisena made Wickremesinghe the Prime Minister in 2015 when he had only 43 MPs. Wasn’t that undemocratic? Fearing public anger, Wickremesinghe delayed local body polls for two-and-a-half years. The provincial polls are delayed. Why is no one speaking about Constitutional violations in these cases?” he said.

As the Rajapaksa camp worked on the numbers, President Sirisena used his executive powers to prorogue Parliament - a strategy that was widely seen as an effort to buy more time.

On the evening of 1 November, more than a week after the split became official, Gotabhaya met Wickremesinghe to discuss the evolving situation. “He went as a representative of President Sirisena and PM Rajapaksa to promise Wickremesinghe a smooth exit and security,” sources said. But Wickremesinghe, who still held the majority in Parliament, refused to budge. “We will go to Parliament along with our PM Wickremesinghe. We will prove our majority,” Harsha De Silva, State Minister of National Policies and Economic Affairs at the time and a close aide of Wickremesinghe, insisted.

Nine days later, with the Rajapaksa camp still short of a majority, Sirisena pulled the plug.