Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Wednesday, 17 October 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

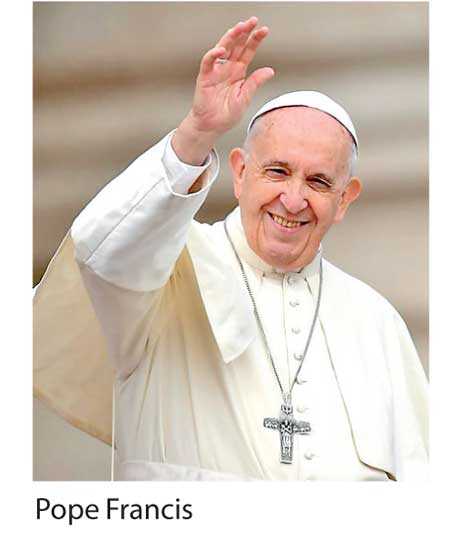

VATICAN CITY (Reuters): Pope Francis on Sunday made saints of two of the most contentious Roman Catholic figures of the 20th century – murdered Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Romero and Pope Paul VI, who reigned over one of the Church’s most turbulent eras and enshrined its opposition to contraception.

In a ceremony before tens of thousands of people in St. Peter’s Square, Francis declared the two men saints along with five other lesser-known people who were born in Italy, Germany and Spain in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Both Romero, who was shot by a right-wing death squad while saying Mass in 1980, and Paul, who guided the Church through the conclusion of the modernising 1962-65 Second Vatican Council, were contested figures within and without the Church.

Both were naturally timid men who were thrust to the forefront of history by the convulsive political and social changes of the 20th century and both had a lasting influence on the current pontiff, Francis, Latin America’s first pope.

In his homily, read with tapestries of images of the seven new saints hanging from St. Peter’s Basilica behind him, Francis called Pope Paul “a prophet of an extroverted Church” who opened it up to the world. He praised Romero for disregarding his own life “to be close to the poor and to his people”.

Romero, who had often denounced repression and poverty in his homilies, was shot dead on March 24, 1980, in a hospital chapel in San Salvador, the capital of the impoverished Central American country of El Salvador.

Romero’s murder was one of the most shocking in the long conflict between a series of U.S.-backed governments and leftist rebels in which thousands were killed by right-wing and military death squads.

It was widely believed to have been ordered by Roberto D’Aubuisson, an army major and founder of the right-wing ARENA party. He died of cancer in 1992.

Romero consistently denounced violence by the Salvadoran military and paramilitary against civilians and urged the international community to stop the oppression.

In his final homily, minutes before he was shot in the heart, Romero spoke of spreading “the benefits of human dignity, brotherhood and freedom across the earth ....”

The 1980-1992 war in El Salvador between the US-backed army and the Marxist guerrillas of the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN), which later became the ruling party, left 75,000 dead and 8,000 missing.

Romero became an icon for Latin America’s poor, appearing on T-shirts similar to those bearing the image of Che Guevara, but his sainthood cause ran into stiff opposition in the Vatican and among powerful conservatives in the Latin American Church.

Both feared that Romero had become too political in life and even more so in death.

The process languished for decades. Francis speeded it up after his election in 2013 and in 2015 the Vatican declared that Romero had died a martyr, killed out of hatred for the faith.

“His martyrdom continued (even after his death). He was defamed, slandered ... even by his own brothers in the priesthood and the episcopate, Francis said in 2015. “(He was hit by) “the hardest stone that exists in the world: the tongue.”

Pope Hamlet

Paul VI, a shy man described by biographers as a sometimes indecisive and tormented Hamlet-type figure, guided the Church through the conclusion of the Second Vatican Council, which had started under his predecessor, and the implementation of its reforms. He was elected in 1963 and died in 1978.

Francis often quotes Paul, showing that he is committed to the reforms of the Council, which allowed the Mass to be said in local languages instead of Latin, declared respect for other religions, and launched a landmark reconciliation with Jews.

Still today, ultra-conservatives in the Church do not recognise the Council’s teachings and blame Paul for starting what they see as a decline in tradition.

Paul reigned in the 1960s when many men left the priesthood and vocations fell sharply in a turbulent era of social change that coincided with the sexual revolution and the widespread availability of the birth control pill.

Despite his many reforms, Paul is perhaps best known for his 1968 encyclical Humanae Vitae (On Human Life), which enshrined the Church’s ban on artificial birth control, saying nothing should block the possible transmission of human life.

The ban, which Paul issued against the advice of a papal commission, became the most contested Church ruling of the 20th century and is still widely disregarded by Catholics.

Paul also became the first pope in modern times to travel outside Italy to see faithful, ushering in a practice which has become synonymous with the papacy.

Paul is the third pope that Francis has made a saint since his election in 2013. The others are John XXIII, who died in 1963, and John Paul, who died in 2005.