Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday, 8 February 2020 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

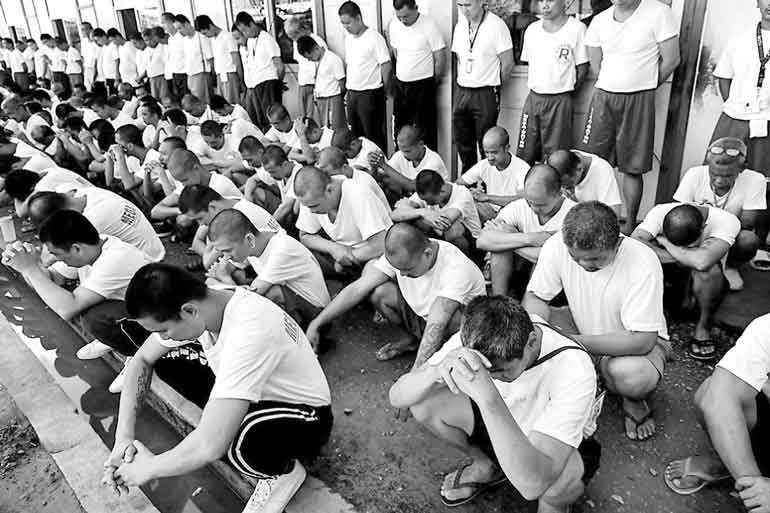

Drug rehab patients gather for a head count at the Mega Drug Abuse Treatment and Rehabilitation Center, in Nueva Ecija province, north of Manila, Philippines 9 December 2019 – Reuters

MANILA (Reuters): Colonel Romeo Caramat oversaw the bloodiest day in the blood-soaked war on drugs in the Philippines – 32 people killed in 24 hours in the province north of Manila where he was police chief in 2017.

Now the head of drug enforcement for the Philippine National Police, Caramat said that ultra-violent approach to curbing illicit drugs had not been effective.

“Shock and awe definitely did not work,” he told Reuters in an interview, speaking out for the first time on the issue. “Drug supply is still rampant.”

Caramat said the volume of crime had decreased as a result of the drug war, but users could still buy illegal drugs “anytime, anywhere” in the Philippines.

He said he now favoured a new strategy. Rather than quickly arresting or killing low-level pushers and couriers, he wants to put them under surveillance in the hope they lead police to “big drug bosses”.

Three-and-a-half years after President Rodrigo Duterte launched a war on drugs in the Philippines with a call to kill addicts and traffickers, his signature policy has failed in many key objectives, according to police officers, health professionals and government officials.

Duterte’s spokesman, Salvador Panelo, did not respond to requests for comment on Caramat’s statements. But in a statement on Jan. 6 responding to a request from Reuters for comment on the anti-drug campaign, Panelo said “we are winning the war on drugs”.

Duterte, however, has repeatedly said in recent speeches and interviews that the anti-drugs campaign has fallen short, blaming endemic corruption for undermining enforcement and the absence of a death penalty for failing to deter crime.

Critics say that problems with the drug war run deeper, pointing to a failure to target high-level drug traffickers, cut the supply of drugs and invest in rehabilitation.

“Heavy suppression efforts marked by extra-judicial killings and street arrests were not going to slow down demand,” said Jeremy Douglas, the Southeast Asia and Pacific representative for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in Bangkok.

“There has to be a focus on prevention and public health, coupled with intelligent policing that takes on transnational crime.”

Caramat’s criticism of the tactics that marked his tenure as Bulacan province’s police chief is remarkable given the nationwide fame he enjoyed for the killings, and the rapid promotions that followed.

After news emerged of the one-day death count in Bulacan in Aug. 2017, local media reported Duterte saying “Let’s kill another 32 every day. Maybe we can reduce what ails this country.”

Caramat estimates “hundreds” died in Bulacan when he was police chief. The Philippines government says 5,532 people have been killed in anti-drug police operations nationwide since mid-2016.

Human rights groups suspect the nationwide death toll is much higher. Amnesty International said in a report last June that “evidence points to many thousands more killed by unknown armed persons with likely links to the police”.

Caramat says that those killed on his watch violently resisted arrest. But he agrees with critics that the anti-drugs strategy has mostly targeted low-level operatives.

“For almost three years, we are arresting the street pusher or the courier. After we have arrested the drug courier, we stopped,” he said in the interview, conducted in December.

After a brief pause when the drug war was declared, transnational crime groups have flooded the country with crystal meth - the most popular illegal drug in the Philippines, known locally as shabu, according to law enforcement officers, government officials and experts.

Vice President Leni Robredo, a political rival of Duterte who was appointed “drugs tsar” last year but fired 18 days later for “failing to introduce new measures” among other alleged shortcomings, said in a report handed to the president last month that the inability to constrict the supply of illicit drugs had been a “massive failure”.

The report added that “attention and resources were disproportionately focused on street-level enforcement”. After being fired, Robredo said that the government was “afraid of what I might discover”.

Panelo, the president’s spokesman, criticized Robredo’s “baseless extrapolations” on drug supply at the time, saying that drug lords had been “neutralized” and that the crime rate had fallen.

“Close to eight out of 10 Filipinos are satisfied with the national administration’s campaign against illegal drugs,” Panelo said.

A survey by Social Weather Stations, a Filipino polling group, in June found 82% of those surveyed were satisfied with the anti-drug campaign.

According to figures provided by the Philippines to the UNODC, crystal meth seizures have climbed in the past year and were on track to more than double in 2019.

However, the average retail price for meth, at $136 per gram, is below the $164 it cost when the war on drugs began in 2016, according to the figures. The cheaper prices, said the UNODC’s Douglas, suggests that far more of the drug is reaching the streets than is being stopped.

A $50 million drug bust in November highlighted the oversupply, according to Caramat. More than 370 kilograms of crystal meth was allegedly found stacked in a wardrobe in a flat rented by suspected Chinese drug trafficker.

But, said Caramat, “it turned out that was just the leftovers”. On the trafficker’s phone were pictures of tonnes of meth stored elsewhere in the Philippines, he said.

Rehab woes

Efforts to cut demand for drugs, including treatment and counselling for the country’s estimated 1.3 million registered addicts, have also been hampered by lack of funding and poor organization, according to analysts and officials interviewed by Reuters.

The limitations of those efforts were highlighted by the small number of patients being treated at the Mega Drug Abuse Treatment and Rehabilitation Centre, in Nueva Ecija, some 100 kilometres north of Manila during a recent visit by Reuters.

Residents rise early at 4.30 a.m., receive medication and counselling, receive medication and counselling, interspersed with prayer, meals and Zumba classes that last until 8.30 p.m.

But while it was built to house 10,000 addicts, the facility has seen just 2,085 severe drug addicts complete the program over three-and-a-half years, according to a PowerPoint presentation from the centre reviewed by Reuters.

Government figures show that in-patient treatment at rehabilitation centres nationwide dropped from 5,648 in 2016 to 5,477 in 2018.

With minimal funding allocated to rehabilitation, most addicts have been unable to access even community-based, out-patient programs, officials and health workers say. Those that get access usually just listen to a lecture or watch a video.

“We were caught with our pants down when the war on drugs started,” said Benjamin Reyes, chairman of the drug reduction committee of the Philippines Dangerous Drugs Board, a government agency.

Shift in strategy

Government figures show that 500 people were killed in the drug war last year, which compares with 3,000 killed in the first year of the campaign.

But rights activists are sceptical that a major shift in the anti-drug strategy is in the works.

“It looks like the numbers are falling but data from government can’t be trusted because they’ve been manipulating or massaging the figures,” said Carlos Conde, Philippines researcher with Human Rights Watch. Reuters couldn’t independently confirm this.

As recently as November, Duterte spoke of killing “drug personalities” and throwing their bodies into Manila Bay.

In December, the Philippines’ new police chief, Lieutenant General Archie Gamboa, Caramat’s superior, was quoted in the Philippine Star newspaper saying that police had been too tolerant combating drug offenders and urged officers to “neutralise” them if they felt under threat. Gamboa did not respond to a request for comment.