Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Friday, 7 April 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Samanthi Bandara

By Samanthi Bandara

Mental health has been emphasised as a core component of health by the World Health Organization (WHO) since the late forties. For many years however, safeguarding mental health remained on the backburner. But mental health issues started gaining priority regionally and globally in the mid-nineties, thanks to a WHO Report titled bridging the gap. After this landmark report, a diverse area of mental health was explored, and evidence based initiatives and interventions came into action. Moreover, the importance of investing in mental health is further emphasised by the goal number 3 of the SDG agenda.

Depression or depressive disorders, is the most common mental disorder, and is referred to as the unknown silent killer.

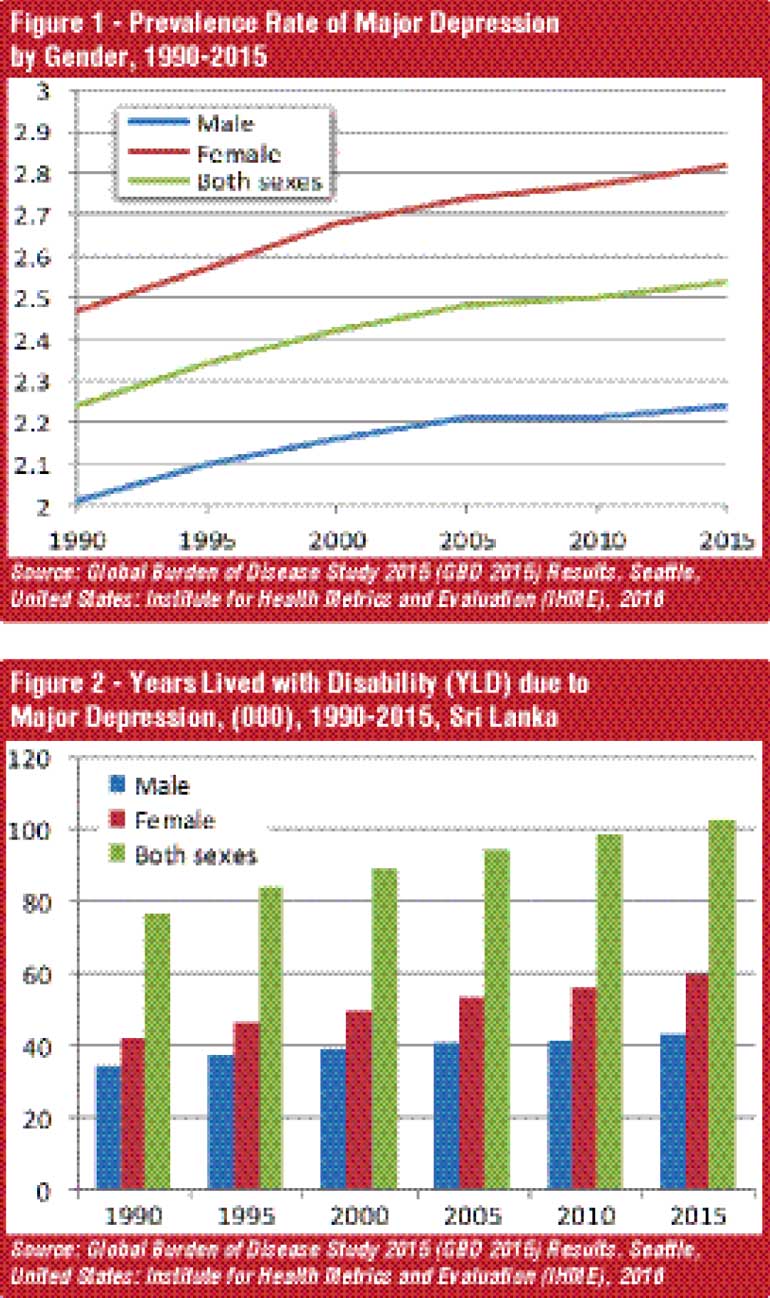

Global health estimates of the WHO found that about 322 million people suffered depression in 2015. As such, approximately four out of 100 people suffer from depressive disorders. In terms of gender, females are approximately 1.5 times more likely to get depressed than men. Prevalence is relatively higher among older persons between the ages of 55-74 years. Depression is the largest contributor to non-fatal disease burden in the world. Another crucial aspect of depression is that severely affected people are more likely to attempt to inflict injuries to self – suicide or other forms of physical harm. As per global health estimates of the WHO for 2015, there were around 802,321 reported cases of depression in Sri Lanka. The prevalence of depressive disorders in Sri Lanka (4.1%) does not considerably differ from the global and South-East Asia region’s figures (4.4%). With regard to the major depression, prevalence and the disease burden have increased over the years (Figure 1). As in other parts of the world, prevalence is higher among females.

With regards to the disease burden, number of years lived with disability has also increased over the years. Tragically, Sri Lanka lost about 103,113 of life years due to major depression in 2015 (Figure 2).

Many studies have found that poverty and low income can push people towards depression. A study published by the Journal of Affective Disorders on Depression in Sri Lanka revealed that the lack of basic amenities and poor financial resources are strongly associated with depression among men in Sri Lanka. Being unable to fulfil basic needs such as food, water, sanitary facilities and housing, and unemployment also contribute to depression in men in Sri Lanka.

Depression is a health concern that cannot be ignored as it leads to social and economic repercussion and could even shorten the span of productive lives due to suicide. Many studies found that depression reduces productivity, increasing health care costs and staff turnover. The Integrated Benefits Institute says employee absenteeism and presenteeism caused by depression reduced productivity by 80%. From the employers’ perspective, lost productivity accounts for 70% of the total cost of depression while medication accounts for the remaining 30%. Haslamet at (200) found that symptoms and medication of depression weaken work performance, and leads to workplace accidents. Impaired work performance caused by depression also weakens the economic and social capabilities of individuals. According to WHO, the loss of productivity at workplace due to depression and anxiety causes losses of about $ 1 trillion per year or approximately $ 130 per head, globally. Accordingly, investing in tackling depression can benefit not just individuals, but the economy as well. Investment in treating depression can result in better health and higher productivity in the work place. In this context, Sri Lanka can also gain $ 4 for every $ 1 invested in treating depression as WHO stated.

Providing comprehensive and quality mental healthcare services in terms of promotion, prevention, treatment and rehabilitation with effective, accessible, equitable and affordable for the entire population is a challenge for every country. Likewise, Sri Lanka is confronting three critical issues in terms of service provision, financial resource mobilisation, and rigorous information system within the country.

In Sri Lanka, depression is simply treated as a component of mental health policy, and therefore, the national mental health interventions are not tailored specifically towards tackling depression.

However, Sri Lanka has taken significant steps over the years to address mental health issues with the assistance of various development agencies. At the foremost, Ministry of Health considers mental health as a core component of non-communicable diseases and therefore a separate directorate for mental health is in place. Secondly, the initial Mental Health Policy for Sri Lanka 2005-2015 is now being revised for the period of 2015-2020, and preparations for the mental health action plan 2015-2020 is underway.

Medical services are provided through hospital networks at national and regional levels, with multidisciplinary teams of professionals (Consultant Psychiatrists, Medical Officers of Mental Health/Psychiatrists, psychiatric nursing officers, Community Support Officers (CSO), Psychiatric Social Workers (PSW), Occupational Therapists). While there is only a single hospital designated for mental health services (National Institute of Mental Health), 23 psychiatric in-patient units/wards, 86 outpatient clinic centres and 250 outreach clinics are operated throughout the country. In addition, day-treatment facilities as well as 22 intermediate mental healthcare rehabilitation units are also being managed by the Health Ministry. Apart from the hospital based treatments and services, psychiatric nursing officers, CSO, and PSWs are closely working with other community health workers (MOH, Public Health Midwife etc.) to identify people with early signs of mental illness and to direct them for continuous medical treatment and counselling.

Adequacy and rationality of financial resources being mobilised for mental health is still questionable. One reason is that, the Health Ministry spends a large portion on curative care while a very small amount is being allocated on prevention and health promotion. While treating the mentally ill people at hospitals, strengthening the preventive and promotional measures on mental health is also important to reduce the incidence of mental health cases.

Developing evidence-based mental health intervention and utilising financial resources effectively can only be done with proper information on mental health. However, Sri Lanka is still far behind of maintaining a unique information system on mental health within the country.

Thus, mental health services in Sri Lanka have room to improve, especially with regard to their reach, when considering the increasing rates of depression. One reason for this could be irrational resource allocation where all the sophisticated and intermediate mental healthcare facilities are concentrated only at big hospitals. More than two third of Health Ministry’s expenditure on mental health, excluding provincial allocations ($ 6.4 million out of $ 8.5 million in 2008/09), is directed to main psychiatric hospitals.

Spending on prevention of mental illnesses and promotion of mental health is minimal. As such, the poor, especially those in rural areas, have limited access to mental health facilities. A patient-centred service model can be a possible solution to expand the coverage of services. One of the ways to implement this is by integrating mental health service, into the existing decentralised community healthcare system, as part of Maternal and Child Healthcare services.

Next, mental health services can be coupled with existing primary health care (PHC) service system that can enable community base intervention, and build social capital to sustain the continuing care. District Mental Health Programme in India has already integrated mental health into PHC in Kerala. However, adequate physical and human resources are essential for the successful implementation of such measures. A multisectoral approach towards mental health financing, with a proper coordination mechanism to link other ministries, could improve the management and coordination of efforts and reduce the wastage of resources.

Absence of information on Depression (and other mental health disorders) is another obstacle which hinders the proper planning and implementation of measures to address mental health issues. None of the routine national surveys collect data on common mental disorders – Depression and Anxiety. Even now, Sri Lanka relies on fragmented sample studies by independent researchers and international data bases such as WHO, Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Therefore, the Ministry of Health should develop a comprehensive data base mechanism, invest on mental health research and carry out evidence based interventions.

(The writer is a Research Officer at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ – http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/)