Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Tuesday, 9 October 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Fathima Riznaz Hafi

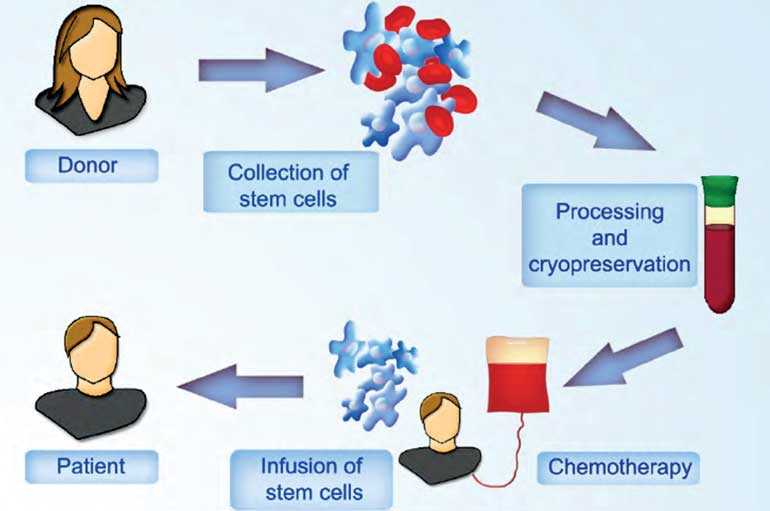

Allogeneic stem cell transplant is a cutting-edge treatment for cancer whereby healthy blood-forming stem cells are collected from a matching donor and transplanted into the patient to replace a diseased or damaged bone marrow thereby suppressing the disease and restoring the patient’s immune system. This type of transplant is different from an autologous stem cell transplant, which uses stem cells from the patient’s own body. In this interview Parkway Cancer Centre Singapore Senior Consultant Haematology Dr. Lim Zi Yi shares insights into this innovative treatment. Following are excerpts:

Q: What is allogeneic stem cell transplant?

A: For some types of blood cancers that are very aggressive, we need to do a stem cell transplant to replace the bone marrow. ‘Allogeneic’ means the cells that are to be transplanted are coming from a donor. We have to find a well-matched donor to replace the bone marrow so that hopefully the patient can recover with cells from someone who is fitter and healthier enabling the bone marrow to heal well with a better immune system to fight cancer.

This is a very tried and tested method for doing transplants; it’s been around for more than 50 years now and more than a million such procedures have been performed worldwide. We have done many in Singapore and also when I was in King’s College, London, where we were one of the largest transplant centres in Europe.

Allogeneic stem cell transplant is a very complicated process that we need to be very careful about and need to have the infrastructure to support it. Also, we need to make sure that we have well-matched donors to support it. It can sometimes be family members – brother or sister – but the chances of brother or sister being matched is one in four – you have a 25% chance; sometimes people have very small families nowadays, or you might not have any brothers or sisters. If you don’t have a family member match then you have to search on a registry; there are a lot of registries worldwide and they are all linked by the internet, so you go on a computer system and try to find a donor somewhere in the world.

The chances of finding a donor are related to ethnicity; so for example, if you’re a Caucasian, the chances of you getting a donor is probably around 80 to 90% worldwide because there are a lot of Caucasian donors; Germany and America have very established registries; even for Chinese the chances of finding donors is around 60-70%.

Q: Why is ethnicity important when finding a donor?

A: Your tissue type is related to your ethnicity; so if I were to find a match for you on a registry, chances are there will be someone in some other part of the world but of similar dissent; it’s very rare that you find a Chinese matching an Indian, because it is just linked from there. So that is one of the challenges – because while we have big registries for Chinese and big registries for Caucasians, the registry for certain sub-ethnic groups like Indians or Sri Lankans is far less.

In Sri Lanka you don’t have a donor registry; in many other parts of the world – like in India they are just starting to develop one but it’s not quite mature yet, so because of that, just purely statistically it’s much harder to find a donor for someone in Sri Lanka than a Chinese patient in Singapore.

That been said, we do find donors – we’ve done transplants for Sri Lankan patients before, but sometimes we have to really search – the donors come from different places – sometimes from America, sometimes from Germany – because there are big sub-communities there who have signed up.

Allogeneic stem cell transplant is highly successful world-wide now with the cure rate for adult leukaemia for the standard patient being around 50-60%. With the technology we had in the past we needed donors who were 100% match – we needed it to be a full match; nowadays even with a 50% match we can still do a transplant; that allowed us to increase the donor pool as well. So with some ethnicities where there may be less donors available, since the technology has allowed us to do matches better, we can actually still do a transplant; now almost everyone has a higher chance of finding a donor!

Q: Are the risks high for this type of procedure?

A: Yes, it’s a major procedure, in that the patient’s immune system gets suppressed for a period of time and the risk of complications are high from that. In addition, there is a risk of rejection – even though you match it well, when the donor cells start growing in the body, they can turn around and fight. What happens here is a condition called ‘Graft versus host disease’ (GvHD), which might occur after an allogeneic transplant. In GvHD, the donated bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cells view the recipient’s body as foreign, and these donated cells attack the body. That can become quite a critical condition.

Here there are a few things we need to do – one is the environment has to be clean and protected; the procedure needs to be done in a specialised setting. In Singapore we do it under strict hygienic control and even after the transplant we still maintain that setting. Even for donor cells, for reducing rejection and complication, we have to give a special cocktail of drugs and techniques to curb infection.

Q: How long does the treatment take (hospital stay, etc.)?

A: It’s a long procedure. From the point of coming in for a transplant, they need to be in-patients for three to four weeks, because we have to give them chemotherapy to clear off the bone marrow, we give them stem cells which go into the body, and there’s a recovery process that takes another two weeks; so the whole process on average takes around three to four weeks.

Most patients get through the transplant period. The biggest risk quite often is actually when they go home, because that’s when – for the first year – their immune system is still weak and imbalanced, thus making them prone to infections. So it’s a year or more long process where you have to constantly manage these patients. It’s a complex process which requires a lot of attention and care.

Q: Is the treatment very costly?

A: This is an extremely powerful but also extremely costly new type of therapy. But because it works so well, a lot of companies are now developing it. Cell therapy is not accessible to many parts of the world yet; this is where health economics comes in – because some of these drugs for chemotherapy can be at a cost of $ 10-20,000 per month like many of the new drugs. However, I think the cost will come down significantly over the next few years.

Singapore is one of the leading centres in the region for healthcare and medical tourism, with its well-developed hospitals and facilities which are at world-class level. Treatment is costly but still much cheaper than in US. One of the reasons our doctors from Parkway come to Sri Lanka is to exchange ideas with local doctors on how to cater to Sri Lankan patients and we also discuss means through which they can gain access to this type of treatment.