Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Saturday, 1 May 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Surya Vishwa

By Surya Vishwa

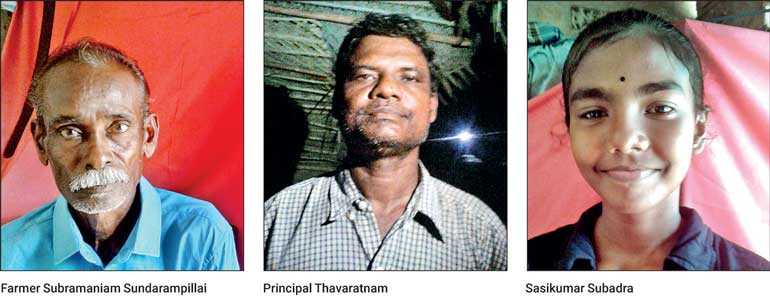

Sasikumar Subadra is 13 years old. This means she has no recollection of Sri Lanka’s three decades of civil war. She has not watched the sad fate of a nation’s citizens being divided based on geography and ethnicity.

She lives in Kilinochchi, once an amphitheatre of bloodshed. Her uncle was an LTTE member who surrendered to the Government after the military defeat of the rebels. She does not seem to be aware of all these complexities as she prepares for a school dance audition.

Her biggest fear of the moment is that she will not do well as a dancer. If someone were to tell her that her fate could well have been different and that she could have been preoccupied with explosives and guns, she would not have understood that alternative reality. However this was the reality that many her age were cast into 12 years ago.

Sasikumar prattles on about dancing, gives a small demonstration and then speaks in careful English to say she wants to visit Colombo. Colombo, the capital city of the country, is still a distant dream and she does not really know what to expect. She has seen some pictures of big buildings but that is not what she wants to find in Colombo. She wants to find ‘Sinhala friends’. So far she has none.

- Undiscovered geniuses exist here in the remotest of places, where one can hardly find a bus and where people are lucky if they can earn enough to afford one meal in three days

- Their only hope is education but being educated may not get them a job. What they want most of all is not just to be job takers but job givers

Subramaniam Sundarampillai

Her uncle’s father in his 70s is seated nearby listening to her. He cannot understand the English words she uses but he can manage some Sinhala.

He recalls his Sinhala friends from his farming days in the Padaviya area in the 1970s. He is referring to a rural Sinhala village that borders the north which became a target of LTTE terrorism after 1984.

“We used to cultivate rented agrarian land in that area together. The Sinhala farmers used to come back after the April New Year holidays with their traditional sweetmeats following the celebrations at home. Then too, I lived in Kilinochchi,” says Subramaniam Sundarampillai.

“We attended each other’s weddings and funerals of relatives. I do not know whether they are dead or alive. This war… it changed everything,” he states.

His son had joined the LTTE in his early twenties and after over 15 years as a militant, surrendered to the Government in May 2009. However I do not talk to him about this chapter of his son’s life. His son after his surrender has successfully completed the Government’s rehabilitation and social integrated program and is today an exemplary citizen. The entire family focuses on education in the strongest manner possible. Their only hope is education but being educated may not get them a job. What they want most of all is not just to be job takers but job givers.

T. Sundarampillai

“I started a shop but there were many difficulties to get that going,” says T. Sundarampillai, wife of Subramaniam.

“I started a shop but there were many difficulties to get that going,” says T. Sundarampillai, wife of Subramaniam.

With an assertive and friendly personality, she is the women’s leader for several village organisations in the Kokkuthuduwai area in Mullaitivu where she lives with her husband and daughters but often comes to Killinochchi to visit her children and relatives who live there.

“I have eight children; four girls and four boys. They are very hardworking but struggling and I do not want to depend on them. I am trying to raise money to complete digging the well in my house to assist in domestic agriculture. I had initial success with my small grocery store but it was difficult with no banks or any other financial institution helping us at least a little. A few NGOs assisted in some scale financing those days after May 2009. They are nowhere in the north now. My youngest daughter is 22 years old and she has scored very high results at her Advanced Level. She has no job. She is very good in accounts. She is looking for a job. Do you know if there are bank jobs here?” she asks.

This is a question she and many others would ask any visitor from the south: Do we know anyone who could give them a job? However they also want to be job creators.

“We do not want free money from the Government or anyone. Give us loans to create jobs. And if there are big companies that want to set up businesses here if they recruit us we will work hard for them,” she says.

“If the Government could give us land, that will greatly help us. Most of us have lost our deeds to our lands in the 30 years we spent being displaced. Some of our land has been taken over by the Forest Department. Many of us do not have any land at all. All of us are efficient at cultivation and agro industries which we can do if we had land,” she notes.

The Colombo-linked private sector presence in areas such as Mullaitivu and Kilinochchi is almost at a non-existent level. There are no visible State or non-State skill development/vocational training and industrial development opportunities for the youth of the north. If detailed feasibility studies are undertaken by the private sector, Sri Lanka’s north will very likely be seen to have one of the most dedicated, creative and intelligent work forces.

“My children like to create things. My son has invented some machines to be used as egg hatchers. He is not an engineer but he thinks like one,” says Sundarampillai.

What she emphasises about her son is true of a majority of northern youth who seem to give meaning to the cliché ‘necessity is the mother of invention’. Many of them create items such as photocopy machines out of throw away machine parts because they cannot afford to buy the new ones. The north of Sri Lanka is indeed a haven with a keen workforce to kick-start industry in the country.

Undiscovered geniuses exist here in the remotest of places, where one can hardly find a bus and where people are lucky if they can earn enough to afford one meal in three days.

Although opportunity is less in the war-scarred north, the evidence of which is still visible with bullet-riddled abandoned buildings around the district, the people of the region do not give in to self-pity or moroseness. Even if they talk about their hardship, it is evident that everyone is working to the maximum level they can, utilising every available opportunity

Thiruselvam Thavaratnam

“If you will listen carefully I will tell you how to make anything you need with palmyrah,” says Thiruselvam Thavaratnam, a 48-year-old author and school principal living in the picturesque Karainagar area in the Jaffna District.

Having authored dozens of books in the Tamil language on a host of subjects ranging from spirituality to aquatic resources as well as Sidda medicine, he is currently writing on the productivity of palmyrah as a natural resource for both food and home based products. Functioning as head of the Arali Murugamoorthy Vidyalaya, he holds a Bachelor of Arts Degree from Peradeniya University and a Diploma in Aqua Bio Technology.

The writing of his book on palmyrah is accompanied by rigorous practical research on the usefulness of this tree and he is surrounded by chairs made of palmyrah wood, an outdoor hut, tables, and a mind boggling range of palmyrah sun dried or steamed food that can be preserved. All of this is done by himself, after returning from school.

“I encourage the teachers in my school and the students to be creators of things, not to limit themselves with theory. That is true knowledge. Whenever I write a book I accompany it with a range of practical knowhow relating to the subject. I use meditation to enhance my knowledge process,” he says.

In the next two years he is hoping to develop and open out his land to those who want to meditate and learn about Siddha medicine as well as the natural resources of the north such as palmyrah, he says.

“Meditation is part of the knowledge process. When the mind is cluttered there can be no genuine knowledge gathering,” he explains.

Although opportunity is less in the war-scarred north, the evidence of which is still visible with bullet-riddled abandoned buildings around the district, the people of the region do not give in to self-pity or moroseness.

Even if they talk about their hardship, it is evident that everyone is working to the maximum level they can, utilising every available opportunity.

Charles Shelton

“It is very easy to learn how to repair a photo copy machine,” says Charles Shelton, who has learnt this skill solely by watching YouTube videos available on the internet. Shelton runs a very successful photocopying shop dedicated to education and is one of its kind not only in Puthukkudiyiruppu, a small town in Mullaitivu but probably the entire country.

He says teachers and students come from out of the district or get him to post the educational material. In his shop there are rows and rows of teacher and student training guides and other education-related documents that are provided by Sri Lanka’s National Institute of Education (NIE). These are neatly bound and sold for just the photocopy cost of around Rs. 3 per page.

His idea to set up a shop for photocopying was arrived at between May 2009 to 2011 while he was receiving skill training provided at the Government rehabilitation centres for ex LTTE militants who surrendered at the last phase of war that ended on 18 May 2009. He is among some 12,000 former LTTEers – the group’s entire fighting force, which were pardoned under a general amnesty adopted by Sri Lanka and put under an international standard de-radicalisation and social integration oriented rehabilitation program.

“My wife started this shop when I was undergoing the rehabilitation program. At that time we were not thinking of education as a specialised area to focus on but I was informed that many students and teachers are coming to the shop asking for diverse educational material. They did not have computers at home or internet facility to access these material online. After I returned from the rehabilitation centre I went through all the official education based internet sites affiliated to the Education Ministry and the Government education institutes. I then downloaded them categorising the different content and bound them as books. I also took the needed steps to create awareness about these material,” he explains.

He has also identified some of the best and senior most teachers of the area and have started creating ‘knowledge papers’ for those sitting for exams such as the Grade 5 scholarship exams and the Ordinary Level and Advanced Level exams. He says he posts and couriers sets of these papers to all over Sri Lanka.

“We do not want a single person to be tricked into terrorism again. If education is provided adequately and equal opportunity given to all persons, no person can make innocent youth become terrorists. Myself and many others like me are doing our part to make knowledge accessible to youth of the North for this reason,” says Shelton displaying his maimed hand.

(Note: This article is produced as part of an initiative by the Harmony page to promote national reconciliation and to commemorate May as a month dedicated to peace in this 12th year anniversary of ending Sri Lanka’s armed conflict.)