Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Monday, 8 November 2021 01:08 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Ernst & Young – Colombo Strategy and Transactions Advisory Services and Sustainability Advisory Services Partner Buwanesh Wijesuriya

Ernst & Young – Colombo Financial Accounting Advisory Services Partner Hiranthi Fonseka

|

|

EY: Sri Lanka is taking up Sustainability and ESG (Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance) on its top priority. Numerous strategic initiatives proposed by the country leadership reinstating the government focus to supporting and promoting of the United Nations Sustainability Development Goals (SDGs) to achieve transformation towards a sustainable and resilient society which includes commitment to Carbon Neutrality by 2050, halve Nitrogen Waste by 2030 through the Colombo Declaration on Sustainable Nitrogen Management, to limit the overuse of artificial fertilisers – to help address health concerns, to increase the contribution of renewable energy sources to 70% of national energy needs by 2030, etc. To achieve these laudable objectives, the support of technology, skills development, investment, and financing must follow through.

Sri Lanka would be in a better position to be able to attract sizeable FDIs as well as achieve its sustainability goals when ALL fall in line and see through the very same strategic lens for defining how value is created, delivered, and measured across all verticals, says Ernst & Young Colombo Transaction Advisory Services Partner Buwanesh Wijesuriya.

Why ESG?

The increasing focus for a framework like ESG helps analysing organisations consciousness to accomplish positive climate action, building a more sustainable, resilient future based on such factors that are generally not covered under mandatory reporting.

i.e., Generally, environmental factors address topics/concerns such as waste management, emissions impact, energy efficiency, air and water pollution, environmental protection, and biodiversity loss and restoration, etc. Social factors take into consideration human rights, labour rights, working conditions, health and safety, employee relations, employment equity, gender diversity and pay inequity, anti-corruption, and impact on local communities, etc. Governance factors comprise issues on ownership and structural transparency, shareholder rights, board of directors’ independence and oversight, diversity, data transparency, business ethics, and executive compensation fairness, etc.

In summary, what is typically looked at is, another way of assessing a company without solely looking at its profitability and balance sheet but paying attention to how the performance impacts the broader society at large. Simply, ESG helps stakeholders, especially potential investors, to gauge whether the business is a ‘good corporate citizen’ and a ‘worthy investment’.

Findings of a survey conducted by EY Global

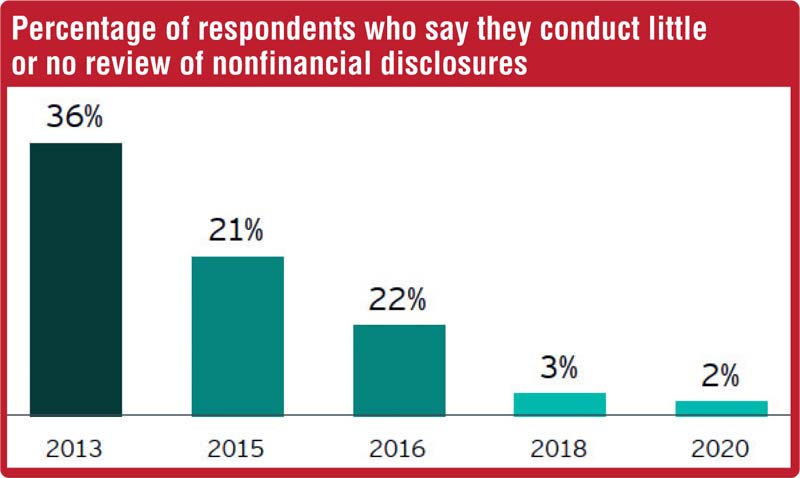

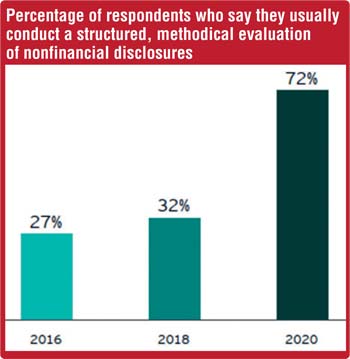

EY study shows “Investors are stepping up the game when it comes to assessing the performance of companies using non-financial factors. Overall, 98% of investors surveyed evaluate non-financial performance based on corporate disclosures, with 72% saying they conduct a structured, methodical evaluation. This is a major leap forward from the 32% who said they used a structured approach in 2018.”

Regulator perspective

At present, numerous ESG frameworks are used by organisations. Among these, the one widely used in Sri Lanka is the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). This framework is recognised as one of the most holistic approaches available to determine how an organisation affects the world in terms of its existence and operations. United Nations Sustainability Development Goals (SDG’s) and Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) are a few other frameworks used by organisations internationally. Regardless of the framework used, the quality of the ESG reporting is only good as the execution of the policies, the data collected and the governance surrounding the monitoring and reporting.

In the United States, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requires public companies to disclose certain ESG information, such as a description of human capital resources and any measures or objectives which the management perceives as material to understand the performance and direction of the business. In addition, the SEC issued guidelines in 2010 with directions on US securities laws and regulations requiring disclosures such as climate-related information, depending on a company’s circumstances.

In EU, a proposal in April 2021 was presented to replace reporting requirements under the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD), requiring large public-interest companies with more than 500 employees to disclose environmental, social, and employee-related matters, such as anti-bribery, corruption, and human rights performance. The proposed Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) will extend the scope to include large companies and all companies listed on EU-regulated markets in the EU (except listed micro-enterprises). The CSRD brings sustainability reporting closer to financial reporting by requiring “limited assurance” of sustainability information by a company’s auditor or an independent assurance services provider. Later, there will be the option of moving forward to “reasonable assurance”.

Where does the frameworks fall short?

Ernst & Young Financial Accounting Advisory Services Partner Hiranthi Fonseka explained that the frameworks do a reasonably good job in terms of streamlining disclosures when one chooses to disclose on a particular criterion. However, Fonseka explained that all frameworks alone would not facilitate a comparison of company A and company B. She said that it depends on whether the reporting organisation has a robust process in place to help determine what is material and relevant to their stakeholders and achieve entirety of disclosures.

The GRI framework brings in a lot of subjectivity when attempts are made to carry out a comparison between companies. This is due to diverse views around what is more relevant to the reporting organisation based on its sector, industry, or organisation values and other focus areas. So, some level of uniformity must be introduced to facilitate the need for comparisons. For example, your business focus may hover around environmental factors, whilst for others it’s social, and for another it’s governance. Many people in a room can give rise to various opinions as to what they perceive as more relevant. EY teams believe the subjectivity in some frameworks to determining what is material and relevant to the reporting organisations' stakeholders leaves room for an organisation to bombard readers with data that bear no relevance to the overall mission of the organisation.

The flip-sided investor perspective

A global EY survey reveals an increasing investor preference for formal framework to be in place when communicating sustainability initiatives.

In the past several years, the dynamics of the sustainability debate has dramatically changed, with mainstream investors noting that sustainability issues impact the risk, return and value of companies in the long term. This has resulted in investors increasingly wanting/demanding comparable, consistent, and reliable information about a company’s sustainability performance. This change is considerably influencing securities regulators to be involved and, likewise, corporate boards to seriously think about and react to sustainability issues. Financial institutions show an increase in trends to use ESG factors to enhance a company’s valuation, lower investment risk and protect reputation.

Understanding the ESG metrics prior to investing?

Explaining on ESG metrics Buwanesh Wijesuriya mentioned that firstly, an investor may want to define for themselves what’s important to them because some organisations have very specific strategies on ESG, whilst others may have a varying focus on the three pillars of ESG. He deliberated that some businesses may be focused on the social and governance aspects more than the environment or vice-versa. It may also be the case where some organisations may be very general in their approach to ESG, where their primary focus is on reporting any initiatives that they abide by. Some organisations may have been consciously focused on these aspects for a long time whereas some may have just ventured into this journey.

Irrespective of what point the organisation is at, as far as the subject matter concerned, from a potential investor point of view, the organisation must enforce such initiatives within the organisation that would create value to the business and minimising business risks. i.e., Assume two agriculture farming organisations have the same level of ESG reporting. In current context, there is a shift in government policy towards the usage of biological fertiliser in the agriculture farming sector. If we are to assume one organisation has already made initiatives to shift at least part of their production towards using biological fertiliser, such an organisation should find this transition easier compared to an organisation that has not ventured its production to using biological fertiliser.

From an investor point of view, the latter should be attributed with a higher business risk as the effort for it to move towards this transition will be relatively challenging. The former would have already secured its supply chain to acquire biological fertiliser, its market branding would have already visualised such usage and its business returns would have already reflected the impact from such initiatives. The volatility of the return from the latter could be higher than the former, which should be considered by a rationale investor during his decision-making process. Given the same level of ESG reporting in both organisations, a smart investor should have been able to gauge the business risk and return concerning the government policy shift.

Understanding investor interpretations on disclosed ESG data

The quality of the ESG data reported by an organisation largely depends on the robustness of the process in place to capture the data. It also depends on how relevant, and material are the criterion reported to stakeholders. Majority of the organisations in Sri Lanka uses GRI framework. There is a high amount of subjectivity that can come into play in interpreting the reported data specially when comparing between organisations.

Moreover, subjectivity comes into play in the application of the concepts of relevance and materiality. In the current outlook, the way forward would be for the investors to interpret data based on the industry the reporting organisation is functioning in. For example, a tyre manufacturing company could ideally report more data on the environment pillar as opposed to an IT service organisation. However, it does not mean that they should have a lacklustre approach in terms of reporting on the other two pillars. Probably, a tyre manufacturing company will be susceptible to issues associated with the disposal of waste and usage of energy than an IT company. Understandably, in this scenario, the environmental factors would relatively be more prominent than the social and governance factors. This can easily leave room for overrating and underrating on the remaining pillars; hence, this is a pitfall to avoid. An investor making an investment decision should interpret the presented ESG data in this context.

The ESG data will give insights into the qualitative factors of an organisation. Insights such as how does an organisation handle its waste resources, how it looks after customers, does it stay out of trouble with the regulators, does it have a decent management structure that encourages accountability etc. Investors will attribute lower risk premiums to organisations having good frameworks in place whereby attributing higher capital market valuations. Considering the above, these organisations will also be able to attract relatively cheaper funding than those who do not have such frameworks in place. Invariably investors will steer away from companies that are badly run and that may end up having serious scandals in the press that can harm the reputation/corporate image.