Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Thursday, 4 March 2021 00:03 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

1mg Founder and CEO Prashant Tandon – Aditya Kapoor/JDot

Cold Chain Bangladesh is building Bangladesh’s first network of temperature-controlled warehouses using expertise from its decade in the frozen-food and ice cream business – Noorphotoface

Cold Chain Bangladesh driver Noor Mohammad delivers products from the company’s cold storage unit across Dhaka – Noorphotoface

A Shadowfax employee in Bengaluru scans a shipment in the company’s delivery center – Shadowfax

A Shadowfax delivery partner drives through Bengaluru, India – Shadowfax

Lasanda Deepthi behind the wheel of her tuk-tuk (three-wheeled auto rickshaw) in Colombo – Nadun Baduge

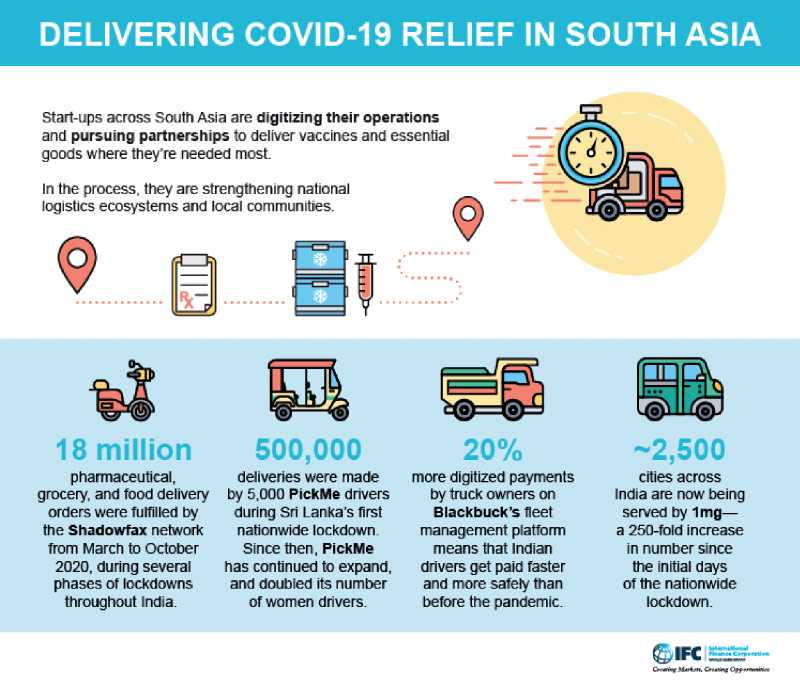

Supply chains are only as good as their weakest link, and COVID-19 has strained these distribution channels like never before. But some tech start-ups in South Asia are responding with new logistics strategies and digital solutions to ensure fast, safe delivery of COVID-19 vaccines, pharmaceuticals, and other necessary goods to last-mile customers. These new solutions are here to stay, analysts believe, and open up opportunities in untapped markets

By Alison Buckholtz

Additional reporting contributed by Savani Jayasooriya

As the COVID-19 vaccine calvary readies itself for deployment, Delhi-based tech entrepreneur Prashant Tandon is preparing for battle. Fighting the pandemic, he believes, depends on the organisation, coordination, and delivery of an arsenal of health-related services and products. Getting the logistics right is critical not only to public health, he says—it’s a chance to prove that partnerships across industries, the private sector, and government produce results for everyone.

When the virus first reached India and the government imposed a strict lockdown, Tandon’s company, the digital health platform 1mg, an IFC investee, went into what he calls “mission mode.” Delivery drivers and front-line workers brought medicines to customers’ doors and collected samples for a range of lab tests. As the pandemic progressed, the company also boosted telemedicine offerings to patients and collaborated with government regulatory agencies to clarify guidelines for e-pharmacies, and actively pursued partners in geographical areas where third-party logistics companies are not operational. It is now setting up a nationwide cold chain infrastructure for COVID-19 vaccines.

Responding to COVID-19 in a country of over 1.3 billion people is forcing 1mg to rethink its core strategies—because this is a significant and important global disruption, not a one-time spike, Tandon said. The company is especially focused on how to mainstream technology into health-care services and related logistics to better track, monitor, and deliver medicine and health products. “Right now, there’s almost no traceability,” Tandon said. “Things like soap and matchboxes have bar codes, but not medicines. When it comes to something as important as vaccines, we need an entirely traceable supply chain so we can be confident and comfortable.”

As with 1mg, other start-ups in the region are remaking themselves to respond to diverse COVID-19-related logistics needs. In India and throughout South Asia, “This is the time for logistics companies to reconsider the old ways of doing business” to remain relevant, said Venkatachalam Anbumozhi, a Senior Economist at the Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA), who tracks the resilience of regional value chains in South Asia. “Some drivers of change, such as the digitalisation of logistical operations, will be permanent,” he believes.

It’s important to pay attention to the prospects presented by such shifts, according to Omera Khan, a Professor of Supply Chain Management at Royal Holloway, University of London. “If the pandemic was an instructive object lesson in supply disruption, it was also an instructive object lesson in resilience,” she said “To survive this period and protect ourselves from the next crisis, we’re moving from globalisation to regionalisation, and there’s now a real opportunity for local logistics networks to compete in local markets.”

But first, vaccine distribution

COVID-19 has turned many people eager for vaccine-related news into amateur logistics experts. As the term “cold-chain” entered everyday use, headline-readers around the world became acquainted with the stringent requirements for some COVID-19 vaccine shipments—and the necessity of a supply chain that can accommodate those requirements. The stakes couldn’t be higher: A broken vaccine supply chain could stunt the economic recovery and increase the number of lives lost, as PwC’s Health Research Institute put it.

IFC’s $4 billion Global Health Platform, supported by the governments of Norway and Japan, provides financing to close gaps in the supply chain and increase developing countries’ access to the COVID-19 vaccine and other supplies to limit the spread of the pandemic. Financing will also help low-income countries boost their own manufacturing capacity, encouraging investment and job creation.

In South Asia, the virus has already impacted the economy severely. Overall regional growth is expected to contract by 6.7% in 2020, World Bank numbers indicate. In India, government estimates predict that real GDP will contract by 7.7% in 2020-21, though the IMF sees a real GDP growth of 11.5% in 2021-22. In Bangladesh, the World Bank’s Global Economic Prospects projects that GDP growth will likely dip to 1.6% in 2021 because of COVID-19. And in Sri Lanka, the COVID-19 crisis has “exacerbated an already challenging macroeconomic situation,” according to the findings, and the economy may contract by 6.7%. Vaccine deployment is key to economic recovery, the World Bank report concluded.

That remedy requires temperature-controlled logistics, “a crucial but often under-recognised tool” for guaranteeing public health, according to a recent IFC report. That’s because several COVID-19 vaccines need to be transported and stored at low temperatures—colder than Antarctica, in one case—from the factory to the point of use. Though not all of the COVID-19 vaccines being distributed and considered for use in South Asia call for such low temperatures, all require some form of refrigeration, and an unreliable electricity supply alongside a scarcity of refrigerated trucks and warehouses make this problematic, as IFC’s report noted.

Those are logistical challenges that Cold Chain Bangladesh Limited is preparing for. But its corporate expertise came in an unexpected way: from years of transporting ice cream and frozen food.

Cold Chain Bangladesh Ltd. is part of a portfolio of companies owned by Golden Harvest Ice Cream Limited and Golden Harvest Foods Limited, decade-old operations. In 2019—before the pandemic, Chairman Rajeeb Samdani pointed out—it entered into a joint venture arrangement with IFC to build the nation’s first network of temperature-controlled warehouses. Though the pandemic arrested progress, the project is expected to be completed in 2022.

Establishing a country-wide logistics networks for frozen food, ice cream, and pharmaceutical distribution taught Samdani and his colleagues some valuable lessons they will apply to the next phase of operations. “Every country needs to have its own cold chain network,” Samdani said. “It’s a must. Without it, industry is hampered, prices are unstable, and the country is vulnerable.”

Covid-19 has accelerated technology deployment, digitalisation, and adoption of new practices in the logistics sector in emerging markets such as Bangladesh, according to Isabel Chatterton, IFC Director and Regional Head of Industry for the Asia-Pacific Region. The reconfiguration of supply chains “presents interesting opportunities,” she said, noting that in a recently concluded analysis for Bangladesh, IFC identified a potential market size of $ 1 billion for private sector-led investment opportunities in the medium to long term.”

The new integrated cold chain and logistics service company is of interest to many international investors, Samdani acknowledged, but for now his focus is on building the company for its citizens.

“We have the opportunity to play a pivotal role in public health and the growth of the national economy,” Samdani said. “We are making history for Bangladesh.”

Pandemic-era partnerships

Other logistics companies across South Asia are actively pursuing partnerships to help deliver vaccines, medicines, and essential goods where they’re needed most. India’s Shadowfax, an IFC investee that launched six years ago as a logistics platform for express, last-mile delivery service, has reshaped its mission to provide ground services support for vaccine transportation. To do this, it has partnered with SpiceXpress, which will allow deployment of a fleet of over 250 refrigerated vehicles and maintain a sustainable cold chain network for vaccine delivery.

“It is vital to have the right partnership when undertaking a task this critical,” said Rahul Kumar, Head of Network Partnerships at Shadowfax.

Extending the reach of 1mg’s logistics network to remote areas is a priority, according to Tandon, and the company is continually looking into new partnerships to make this possible. “My mantra is ‘Partnerships,’” Tandon said.

Current collaborations offer 1mg the capacity to distribute and administer the COVID-19 vaccine to 50 cities in India, eventually vaccinating half a million to one million people per day. The company has also developed technology to train an on-demand fleet of qualified vaccine administrators, book patient appointments for vaccination, and develop a cold chain distribution infrastructure.

Inoculating the supply chain

Partnerships among logistics competitors is a fairly new development, but reflects recent research from DHL and McKinsey asserting that “supply chain innovation will be essential and collaboration along the value chain will be the enabler for future business success.” That innovation includes the integration of different supply chain services and partners, because the successful and safe administration of a vaccine includes many components.

Warehousing is one of those components. To expand temperature-controlled storage capacity for COVID-19 vaccines in India, IndoSpace, an IFC investee that invests, develops, and manages industrial real estate and warehousing, partnered with KoolEx in late 2020. The alliance will help IndoSpace build three temperature-controlled pharmaceutical distribution centres across India. The first one to open, near Mumbai, will be India’s largest stand-alone temperature-controlled warehousing facility.

“Warehousing and the logistics industry will play a major role in Covid-19 inoculation programs, and by extension in rebuilding India’s economy,” said Rajesh Jaggi, Vice Chairman for Real Estate at Everstone Capital, part of the IndoSpace leadership team. “The warehousing and logistics sector has been one of the most resilient sectors of the Indian economy during the Covid-19 crisis because of its ability to quickly adapt to new demand for last-mile services.

Khan, the supply chain expert, believes that the number and substance of corporate collaborations is a nod to the times. “[Partnerships] are more than just business transactions; companies recognise that they are saving lives with their actions. There’s a culture shift,” she said.

Lowering logistics costs

Another pandemic-inspired culture shift in the logistics sector is taking place in India, analysts believe. “We are seeing increased government engagement with the private sector,” said Arindam Guha, Partner, Government and Public Services Leader at Deloitte India. “This began with repurposing existing capacity for manufacturing and distributing PPE [personal protective equipment], and it continues because protecting 1.3 billion people is a Herculean task.”

This reflects a global trend sparked by COVID-19: governments moving “towards the role of active players in the medical supply chain,” according to a whitepaper produced by the logistics giant DHL. “Lessons learned since the start of the COVID crisis have demonstrated that sufficient planning and effective partnerships with supply chain partners can be important success factors for governments looking to secure critical medical supplies during health emergencies,” DHL concluded.

The Indian government’s focus on partnerships that will kick-start the supply chain comes as part of a wider emphasis on logistics among top-level economic reforms. In 2017, the government created a new logistics division in the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, and it is now nearing completion on a National Logistics Policy that will help lower the cost of logistics. In India, the logistics cost as a percentage of national GDP is 14%, as per a 2020 joint report by Arthur D. Little and the Confederation of Indian Industry. This figure is significantly higher than similar costs in the U.S. (9.5%), Germany (8%), and Japan (11%). That’s a problem because high logistics costs “adversely impact an economy’s competitiveness and in turn act as a constraint on economic growth,” said Priyanka Kishore, Head of India and Southeast Asia Economics at Oxford Economics.

Though the National Logistics Policy aims to address this and other supply chain concerns, some of the proposed actions will be especially helpful during the pandemic and any possible future health crises, according to Shubham Gupta, a Deloitte India partner. One key intervention Gupta finds promising is digital transformation backed by enabling regulations, which would capture and provide data on national supply and demand in the logistics sector.

“Right now, the data doesn’t exist, but it’s an important factor in the logistics sector’s ongoing resilience,” Gupta said. “If we create enough data sets, logistics start-ups will be prepared for future emergencies like the pandemic.”

Enabling the ecosystem

Government openness to tech-enabled logistics platforms and related new policy measures, such as those proposed by the National Logistics Policy, “are important enablers for enhanced logistics” in India’s $200 billion logistics market, according to a 2019 McKinsey report.

Post-pandemic, such dialogue between logistics companies and governments, as well as with the banking sector, will be necessary to facilitate capital injections that will stimulate recovery, said Anbumozhi, the economist with ERIA.

Still, many roadblocks litter the logistics sector’s path forward. Throughout India, fragmentation of the trucking industry is a particularly difficult problem; dated infrastructure and a large informal workforce complicate progress on a national scale. Ninety-nine percent of the market is unorganised, and the lack of coordination causes supply chain disruptions, according to India’s Logistics Skill Council.

“It can be chaotic,” said Uttam Garodia, a founder of Blackbuck, an IFC investee that operates an online platform connecting truck drivers and cargo shippers throughout India. “In the past, fragmentation caused huge gaps in supply and demand. For example, if Unilever needed 10 trucks, it got one. If it needed one truck, it got a dozen truckers calling to offer their services.”

Garodia’s company, Blackbuck, allows shippers to post jobs on a digital loadboard so that truckers can bid on the jobs. It also has contracts with corporate shippers to meet their freight needs across regional clusters. Coordination has helped some clients lower their logistics costs by 10% to 12%, according to the company.

Despite the progress, business dropped 80% when the virus reached India, and supply chain disruptions were ubiquitous, Garodia said. To keep goods flowing, Blackbuck launched its “Move India” initiative two months into the national lockdown to jump-start the stalled sector. Manufacturers, traders and other shippers were allowed access to Blackbuck’s platform at reduced prices. Blackbuck waived commissions and encouraged drivers to return with direct money transfers, trip insurance, and a relief fund for its driver partners who may contract COVID-19 in the line of duty. Automated processes that were already in place, such as the ability to sign for shipments and collect fees digitally, have protected drivers from health risks during the pandemic, Garodia said, and “enabled the whole ecosystem.”

These efforts to respond to the pandemic have helped get trucks back on the road to deliver goods across India, and Blackbuck’s business is only 20% lower than its pre-pandemic activity, according to Garodia.

Nurturing local job creation

Logistics companies that are responding to COVID-19 with strategies like these help keep workers employed, and some start-ups report hiring a significant number of new delivery drivers because of pandemic-related demands. Shadowfax, for example, has hired 60% more driver partners since India’s COVID-19 lockdown began. It now has 50,000 driver partners doing deliveries across 500 cities in India.

Local logistics firms like Shadowfax play a unique role keeping people employed, says cofounder Abhishek Bansal.

Contd. on Page 16

“Employability in logistics is important to me because I came from a poor town and have seen what happens when there aren’t enough jobs to go around,” Bansal said. “In logistics, people can make money just by moving items. People can do part-time ‘gig’ work on their own schedule and help their community at the same time.”

That’s exactly what Lasanda Deepthi, a 41-year-old single mother from Kesbewa, Sri Lanka, loves about her work as a driver for IFC investee PickMe, Sri Lanka’s first ride-hailing app. The service connects drivers of tuk-tuks (three-wheeled auto rickshaws), motorbikes, cars, and vans to passengers in real time. Deepthi was PickMe’s first woman driver when she joined five and a half years ago, and she depends on the income. “Earning through PickMe is a huge deal, and I feel the difference. All what I have is from my own efforts.” she said.

As the pandemic closed its grip on Sri Lanka last year, prompting several waves of lockdowns and strict curfews, demand for essential supplies increased. PickMe partnered with state-owned food suppliers to deliver flour, rice, and household supplies to individual households—pivoting virtually overnight from a logistics company specialising in ride-hailing into a logistics company specialising in delivery of necessities. It also set up an emergency hotline to drive medical staff to and from hospitals. It was the only ride-hailing company operating outside of Sri Lanka’s commercial capital, Colombo, helping to ensure that people in less populous areas could remain mobile and access the goods and services they need.

The shift to an emergency delivery fleet kept PickMe driver partners like Deepthi employed--a tremendous relief, she said, because she is the sole provider for four family members. In addition to doing hospital drop offs, Deepthi and other PickMe drivers have also supplied cooking gas to customers. Although she had never before lifted a gas canister by herself, “I did that too, especially when elderly people needed help. [This job is] not just about dropping someone off or delivering food, it’s a 100% social service,” she said.

Lockdowns and quarantines have made individual consumers more open to trying out tech-enabled logistics platforms than they were before the crisis—especially since there is now hyperlocal service and a growing emphasis on the user experience, said Jiffry Zulfer, the founder and CEO of PickMe. Many people in Sri Lanka hadn’t ever used a smartphone to order anything before, but “COVID-19 made digital mainstream,” he said.

Though Zulfer hadn’t anticipated PickMe serving a public health function when he founded the company, the company’s pandemic response continues to evolve to meet demand. He marvels at the importance of logistics-based technology in dealing with a world impacted by COVID-19.

“We can ease the economic and social hardship of our countrymen by delivering essential goods at a reasonable price, while ensuring the health and safety of our fellow drivers and riders who have come forward to help the country in this dire situation,” he said.