Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Thursday Mar 12, 2026

Tuesday, 26 December 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Surrounded by the sea and boasting an impressive number of waterways inland, Sri Lanka is blessed abundantly in terms of water. But when it comes to water safety, we sink.

With a staggering 1,100 deaths (estimated) a year by drowning, Sri Lanka has fallen short quite dismally in terms of delivering on health and safety obligations in the water.

What’s even more tragic is that all of these deaths are preventable. A look at the comparative statistics provided by Life Saving Victoria (Australia), which is engaged in drowning prevention work in Sri Lanka with Sri Lanka Life Saving (SLLS) – formerly known as the Life Saving Association of Sri Lanka – highlights the severity of the problem.

While 1,100 drowned in Sri Lanka, by comparison in 2016/17 there were 291 drowning deaths in Australia – “alarming differences given the similar population numbers of Australia and Sri Lanka and the greater participation in water activities and larger land mass of Australia,” as highlighted by Life Saving Victoria (LSV).

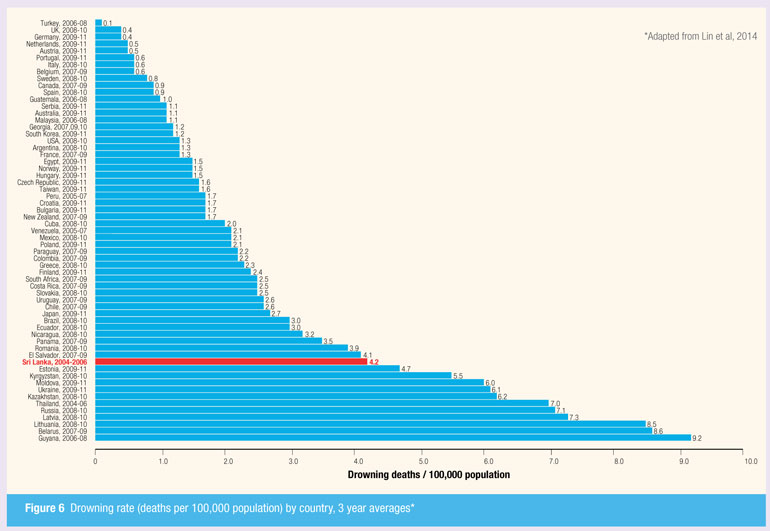

In fact, it states that Sri Lanka has the 12th highest drowning rate out of 61 countries analysed in the 2014 World Health Organisation Global Report on Drowning and the 10th highest when compared with 35 Low and Middle Income Countries.

Water related opportunity in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka has an abundance of beautiful beaches and inland waterways including rivers, lakes, dams and reservoirs, and the water is warm all year-round – providing a great opportunity for locals and tourists alike to enjoy and use for recreation.

Providing a safe environment around water through the provision of lifesaving services enhances the value of these natural water-related assets and there is tremendous opportunity in Sri Lanka for tourist, economic and social development through better utilisation of water related assets, Sri Lanka Life Saving and Life Saving Victoria asserted.

Life Saving Victoria Chief Operating Officer Mevan Jayawardena stated that LSV has been working with SLLS since 2011, starting at a grass-roots level, and most recently moving to a holistic strategic level.

“Sri Lanka is abundantly blessed with beautiful beaches and inland waterways, including lakes, dams, rivers, and reservoirs, which can be accessed all year round. In making these natural waterways safer, there is an opportunity to promote better use of these assets for both locals and tourists. As more people congregate and participate, local micro businesses can thrive and create employment. We have seen this done well in Australia and other places around the world.”

Jayawardena stated that training was started at the grass-roots level with first aid, pool lifeguarding and beach lifeguarding, and progressed to rescue board operations and swim teacher training, while most recently there have been major efforts to build capacity and capability in setting strategic direction and a governance framework for a holistic approach to water safety.

“Our goal is to support the development and implementation of a holistic national plan, which addresses drowning and realises the opportunities that water-related assets provide in Sri Lanka,” he emphasised.

“The people who work in lifesaving must represent the people lifesaving aims to serve. That is the first and foremost reason why both male and female representation is essential. Given lifesaving has only 5% female representation in Sri Lanka, clearly there is an opportunity for development.”

Sri Lanka Life Saving President Asanka Nanayakkara said: “Drowning is the second leading cause of accidental death in Sri Lanka and on average we lose three people per day, which accounts to over 1,100 people per year. Sri Lanka has 1,340 kilometres of coastline and thousands of waterways, including rivers, lakes, beaches and dams, which are used 365 days a year. Many people in Sri Lanka have minimal swimming skills and knowledge of being safe in the water.

“Sri Lanka Life Saving has been working on drowning prevention and water safety for over 70 years, and after connecting with the international community, was reenergised in 2011. Since then, we have made significant developments. We have trained more than 50,000 people in life saving skills and saved over 5000 lives. Lifesaving services are now available throughout the country and there are more than 50 affiliated clubs involved including the armed forces, the Police, Coast Guard, CSD and community groups.”

Nanayakkara noted that over the past two years, their personnel have been deployed to flood rescues situations around the country and they have developed the Swim for Safety program that teaches children to swim in lakes, rivers, dams and pools, in just 12 lessons.

“We have trained, free of charge, over 1,000 children in Swim for Safety and we are now in discussions with the Ministry of Education about making it available to all students in Sri Lanka. Through our journey, we have been supported internationally by Life Saving Victoria, which has provided us with technical and strategic expertise.”

SLLS and LSV drowning prevention work in Sri Lanka

LSV commenced its drowning prevention work with SLLS in 2011, with the goal to halve the number of drowning deaths in Sri Lanka, which is currently in excess of 1,100 per year.

Providing expertise in lifesaving training and drowning prevention is an important way that LSV can contribute as part of Australia’s overseas development efforts, while for the people of Sri Lanka, lifesaving has also become an important way to build stronger communities and enjoy the beautiful waters of Sri Lanka.

Lifesaving training delivery

Each year, six young Australian leaders with lifesaving expertise are selected to travel to Sri Lanka and work with SLLS to deliver lifesaving training to international standards.

Over the past six years, the program has progressed to deliver training in: increased lifesaving skill levels, starting with basic beach and pool lifeguard qualifications, and progressing to beach management and inflatable rescue boat driving. Since 2011, more than 1,000 local personnel have participated in the training, including local lifesaving volunteers, pool lifeguards from local hotel chains, local police and military personnel from the Navy, Coastguard, Army, Police and Air Force.

In 2014, two additional trainers from the Victorian aquatic industry were added to LSV’s efforts, to set up the Swim for Safety Program (https://web.facebook.com/swimforsafety/?ref=br_rs), which teaches survival swimming skills to local children.

With the support of LSV, SLLS has been progressively increasing its capabilities and has delivered new skills to over 50,000 people in the local community.

Sri Lanka Drowning Prevention and Water Safety Report

In 2014, LSV, in partnership with SLLS and the World Health Organisation, released the inaugural Drowning Prevention and Water Safety Report for Sri Lanka.

The report was launched on 26 December 2014, to coincide with the 10-year remembrance of the 2004 Asian tsunami.

The report analyses trends in the 1,100+ (850 on-record) drowning deaths that occur in Sri Lanka each year, to help to identify and implement drowning prevention mitigations.

Drowning data is currently being collated for a follow-up report.

Swim for Safety program research

SLLS and LSV’s research team has continued to support drowning prevention efforts in Sri Lanka through evidence-based research. In 2016/17, this has included monitoring, evaluation and review of the Swim for Safety survival swimming program as well as undertaking collaborative research with the University of Peradeniya.

National Action Plan for Drowning Prevention and Water Safety in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka’s Interim Management Committee for Disaster Management has formed a National Advisory Committee to work to address the issue of drowning prevention and water safety in Sri Lanka.

In July this year, SLLS and LSV representatives conducted a series of workshops hosted by the National Disaster Centre (DMC), to provide expert technical advice.

Areas of focus included:

The next major step required is to bring together government, private sector and the community to implement the National Action Plan. It is only then can an effective and sustainable outcome can be reached to prevent drowning deaths and maximise the value from water assets, Sri Lanka Life Saving and Life Saving Victoria asserted.

Hotel beach lifesaving service pilot

SLLS and LSV worked with Jetwing Hotels in 2015 to set up lifesaving services at the Jetwing Yala hotel in Yala National Park. The pristine beach at the resort was unused by guests and staff, due to the challenging surf conditions.

Life Saving Victoria experts conducted a full risk assessment of the beach, followed by the implementation of lifesaving services to enable the beach to be opened to hotel guests. This involved training local lifeguards, construction of a storage and lifeguard facility on the beach and development of a set of operating policies and procedures. Over 15,000 people have since visited and safely enjoyed the beach at Jetwing Yala.

2017 lifesaving program delivery in Sri Lanka

2018 fellowship program in Australia for female leaders

With support from the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s (DFAT) Australian Awards Fellowship, LSV is working with female members of the tourism industry, the business community and those within SLLS, to increase representation of females involved in community aquatic education, employment and organisational governance.

The fellowship program is divided into two streams:

Stream 1: Aims to empower female leaders to develop skills and knowledge in water safety. Fellows will participate in a range of lifesaving and water safety skills workshops to gain qualifications that meet international standards.

Stream 2: Includes representatives from tourism operators as well as the media who play an integral part in water safety development. This stream is aimed at using water-related assets for tourism development. They will visit a range of locations in Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland, to see how lifesaving services integrate with local businesses and communities to help to promote tourism. The fellowship program will be delivered in Australia in February 2018.

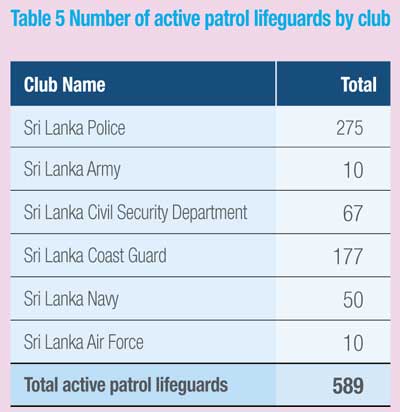

Following the end of the civil war in Sri Lanka in 2009, lifesaving was a welcome deployment option for armed forces personnel. Across Sri Lanka, personnel have been trained in lifesaving skills and deployed to provide lifesaving services at open water locations.

There are over 589 lifeguards in the armed forces and this number is increasing every month. In addition to daily duties there are special duties allocated to various Buddhist, Muslim, Hindu, Catholic and Christian festivals.

[Source: Life Saving Association of Sri Lanka (2014) Drowning Prevention Report Sri Lanka: Laying the foundation for future drowning prevention strategies.]

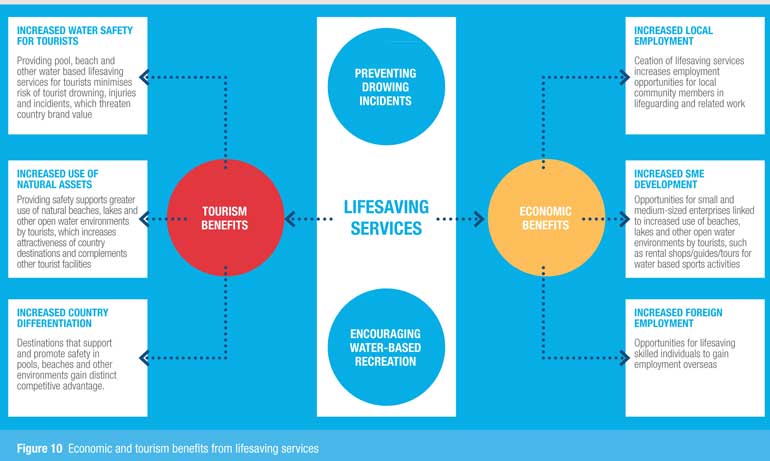

The primary benefits from lifesaving services are preventing drowning deaths and encouraging aquatic recreation. The latter helps create a culture of swimming in Sri Lanka, which is an asset for an island nation. With lifesaving services, recreational swimming can be made available in many places in Sri Lanka including beaches, lakes, reservoirs/tanks and rivers.

In addition to preventing drowning deaths and encouraging water-based recreation, there are economic and tourism benefits that flow from lifesaving services. These include increased water safety for tourists, increased use of natural assets, increased country differentiation, increased local employment, increased opportunities for small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) and increased foreign employment.

Sri Lanka is abundantly endowed with beautiful and accessible open water environments that are ideal for water-based recreation. Complementing these natural environments with lifesaving services makes for a promotion and utilisation of Sri Lanka that is vastly untapped.

It is important for government, businesses and communities to understand the benefits that can be drawn from lifesaving services in Sri Lanka and action strategies for realising these benefits.

[Source: Life Saving Association of Sri Lanka (2014) Drowning Prevention Report Sri Lanka: Laying the foundation for future drowning prevention strategies.]

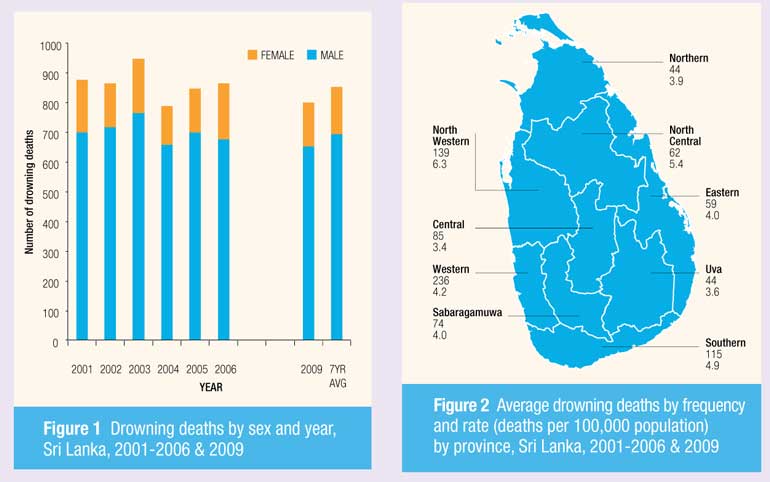

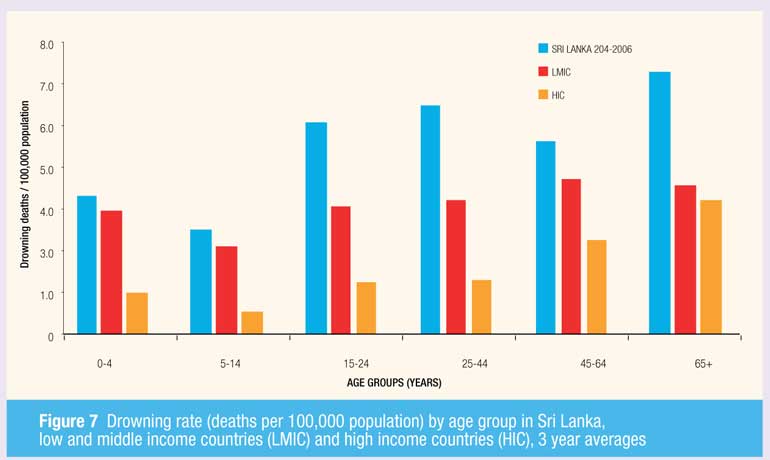

On average, 855 people drowned each year from 2001-2006 and 2009 in Sri Lanka (Figure 1). The drowning rate was 4.4 deaths per 100,000 people in Sri Lanka averaged over the seven-year period.

The average number of drowning deaths and rate of drowning for each province is provided in Figure 2. The Western Province had the highest number of drowning deaths compared to the other provinces, however the North Western Province had the highest crude drowning rate per 100,000 population.

Who is drowning?

Sex: Males were four times more likely to drown than females with a drowning rate of 7.2 deaths per 100,000 population compared with 1.6 deaths per 100,000 for females. Drowning rates were highest among males aged over 15. The male to female rate ratio was highest in those aged 15-24 years (7.5), closely followed by those aged 25-44 years (7.0). The ratio was closest to 1 in those aged 0-4 years (1.8) and over 65 years of age or older (1.9).

Age: Adults aged 25-44 years had the highest number of drowning deaths followed by those aged 45-64 years. However, those aged over 65 years had the highest age-specific drowning rate (8.25 deaths per 100,000), followed by those 45-64 years (5.38 deaths per 100,000). The drowning rate was lowest in the 5-14 year age group (1.94 deaths per 100,000).

Where and how do these drowning deaths occur?

Evidence provided from local rescuers and responders revealed key themes. Males were identified as at greatest risk as confirmed by the statistics. Adults aged 15-44 years were also thought to represent the greatest proportion of drowning victims which was also consistent with the statistics.

Location: Lakes were reported as the key location for drowning incidents in six of the nine provinces. This was followed by oceans/beaches in four provinces; wells/open cisterns also in four provinces; rivers in three provinces; reservoirs/tanks in three provinces; and irrigation channels and waterfalls in one province each.

Activity: Common aquatic activities in the provinces that may place people at risk included, general recreation or play in, on or near water, fishing either for employment or sustenance, other work related activities such as in rice paddies or construction, activities of daily living such as bathing or doing washing in water, as well as participating in recreational aquatic sports and tourism activities.

Contributing factors: Key factors reported to be involved in drowning were, alcohol consumption around water, lack of lifejacket wear on boats, lack of supervision, lack of water safety skills and knowledge, flooding from monsoonal rainfall, uncovered or unprotected wells and reservoirs/tanks.

Drowning prevention issues: Key issues in tackling drowning were a lack of learn to swim programs, lack of identified safe swimming zones with lifesaving services, difficulties for many to access safe swimming environments and/or lessons, lack of resources to promote and deliver water safety education and awareness, and a lack of legislation or ability or enforce legislation governing water safety (such as lifejacket wear and alcohol free zones on beaches).

[Source: Life Saving Association of Sri Lanka (2014) Drowning Prevention Report Sri Lanka: Laying the foundation for future drowning prevention strategies.]

The need for lifesaving services has significantly increased in recent years in Sri Lanka. This is due in most part to the end of the civil war in 2009, which has encouraged local communities and tourists alike to travel more extensively and visit more aquatic environments, including swimming pools, beaches, lakes, rivers and reservoirs/tanks.

This increased participation in aquatic recreation has led to a need to equip more Sri Lankans with lifesaving skills. Teaching lifesaving skills is a proven drowning prevention action, and persons trained can help prevent a drowning death. This person may be a bystander at the scene of a drowning incident who is trained in basic lifesaving skills or a qualified lifeguard on duty. The more people that are trained in lifesaving skills, the greater the chance of lives being saved from drowning.

Led by the Lifesaving Association of Sri Lanka, over 11,000 people have been trained in lifesaving skills between 2012 and 2014.

International training

Since 2012, Life Saving Victoria, in partnership with the Life Saving Association of Sri Lanka, has delivered a range of internationally recognised training programs to Sri Lankan personnel across a range of industries including tourism, swimming and lifesaving and the armed forces. This has helped increase the profile and the importance of developing lifesaving in Sri Lanka.

Each year since 2012, a team of lifesaving professionals from Life Saving Victoria has provided training in CPR, First Aid, pool lifeguard training and surf lifeguard training (including Bronze and Silver Medallion training). Since this partnership began, over 600 personnel have been trained and now provide vital lifesaving services across Sri Lanka.

The Life Saving Association of Sri Lanka has the mandate and training capabilities to offer internationally recognised lifesaving training in Sri Lanka and the partnership is expected to continue.

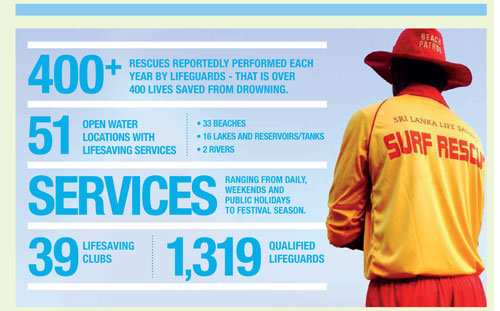

There are 51 lifesaving service locations in Sri Lanka with a total of 1,319 qualified lifeguards performing duties. Over 400 rescues are reported to be performed each year by lifeguards – that is over 400 lives saved from drowning.

[Source: Life Saving Association of Sri Lanka (2014) Drowning Prevention Report Sri Lanka: Laying the foundation for future drowning prevention strategies.]

1. Teach basic swimming, water safety and safe rescue skills to at-risk groups

2. Train bystanders in safe rescue and resuscitation

3. Implement drowning prevention public awareness campaigns to at-risk groups

4. Continue to develop lifesaving services operation

5. Develop a national water safety plan

6. Improve research capability

7. Harness the value of tourism from lifesaving

8. Control access to water and/or provide safety warnings

9. Develop guidelines for safe swimming pool operation

10. Build resilience and manage flood risks

[Source: Life Saving Association of Sri Lanka (2014) Drowning Prevention Report Sri Lanka: Laying the foundation for future drowning prevention strategies.]

Lifeguards play an honourable role in saving lives from drowning, and preventing injuries in water. For the most part, lifeguards are volunteers who are committed to their duty. Unfortunately, the role of a lifeguard is often undervalued in society and Sri Lanka is no different.

Led by the Life Saving Association of Sri Lanka, significant progress has been made in elevating both the skill level of lifeguards in Sri Lanka and recognition of their importance. From a training perspective, pool and surf lifeguards trained by the Life Saving Association of Sri Lanka are recognised by the International Life Saving Federation.

With the support of Life Saving Victoria, the Life Saving Association of Sri Lanka continues to develop capabilities for lifeguard training. From a recognition perspective, the average salary of a lifeguard in Sri Lanka has risen to Rs. 30,000 ($ 230) per month in 2014, compared to an average salary of Rs. 10,000 ($ 75) per month in 2010.

The current average salary for a lifeguard is on par with an entry level sales or banking job and a service employee at McDonalds in Sri Lanka. There are now more young men and women choosing lifeguarding as a profession. In some cases, lifeguards are from impoverished backgrounds and often illiterate. Lifeguarding offers these individuals a pathway to a job and a salary which would otherwise be unattainable.

In gaining an internationally-recognised lifeguard qualification from the Life Saving Association of Sri Lanka, lifeguards from Sri Lanka have a pathway to gaining employment in the Middle East, particularly the United Arab Emirates. This pathway creates an incentive for youths to enter lifeguarding, creating a larger resource pool for local employment which can be more than replenished to compensate for any labour loss to the Middle East.

The average salary for a Sri Lankan lifeguard in the Middle East is Rs. 75,000 ($ 570) per month. For a Sri Lankan, gaining employment as a lifeguard in the Middle East is financially better than gaining employment as a domestic helper in the Middle East with an average salary of Rs. 25,000 ($ 190) per month.

Lifeguarding is more attractive financially and offers a better quality of life for both the person employed and their family circumstances in Sri Lanka. Life Saving Association of Sri Lanka has successfully secured more than 260 jobs since 2013 for Sri Lankan lifeguards in the Middle East.

[Source: Life Saving Association of Sri Lanka (2014) Drowning Prevention Report Sri Lanka: Laying the foundation for future drowning prevention strategies.]