Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Thursday, 10 June 2021 01:53 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

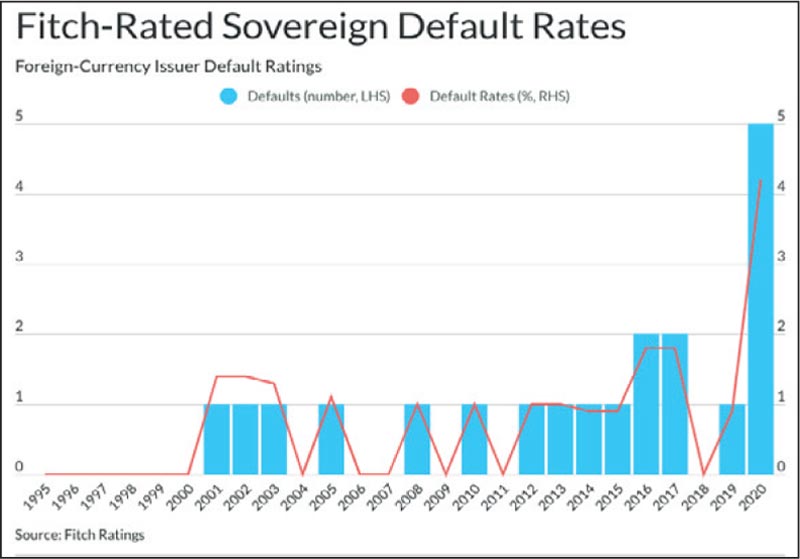

Fitch Ratings said yesterday the sovereign issuer-based default rate rose to a record high in 2020 against a backdrop of weakened sovereign credit profiles due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Downgrade pressures have eased this year, but our ratings indicate that more defaults are possible,” Fitch warned.

Its recent Sovereign 2020 Transition and Default Study shows that five Fitch-rated sovereigns defaulted in 2020, up from only one in the previous year. As a result, the sovereign default rate rose more than threefold to 4.2% from 0.9% in 2019. The previous high was 1.8% in both 2016 and 2017.

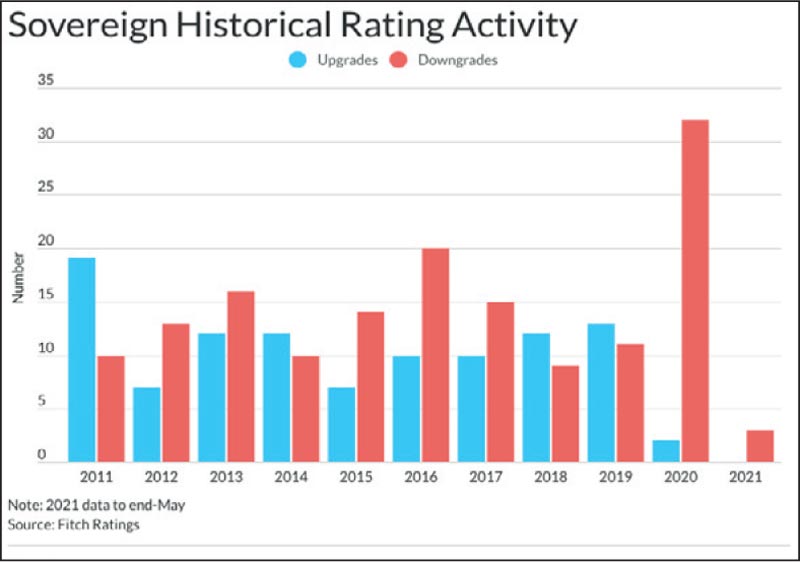

The scale and breadth of the pandemic’s economic impact and of governments’ policy responses put widespread pressure on sovereign ratings, with Fitch downgrading 32 sovereigns in 2020 compared with just two upgrades (both pre-pandemic).

The majority of last year’s downgrades occurred early in the pandemic, between late-March and mid-May. The resulting ratio of downgrades to upgrades was 16:1, whereas the ratio was 0.8:1 in 2019. By comparison, the 2009 ratio following the global financial crisis was 7:1.

Fitch has downgraded three sovereigns in 2021, with no upgrades, but the Outlook changes this year have had a positive bias. Fitch has revised the Outlooks on the ratings of six sovereigns to Stable from Negative, and three to Positive from Stable in 2021, while just one (Kuwait) has been assigned a Negative Outlook.

Increasing certainty that the baseline forecasts for macroeconomic performance and public finances remain consistent with a sovereign’s current rating would support further stabilisations. This would be consistent with the lower conversion rates from Negative Outlooks (which peaked at 44 in mid-2020) or Watches observed in previous systemic and global crises. Rating actions will also reflect the assessment of the medium-term impact of the pandemic.

However, while the initial rating pressure across the sovereign portfolio may have abated, more defaults are possible, as indicated by the fact that 11 sovereigns are currently rated lower than ‘B-’.

The five sovereigns that defaulted in 2020 – Argentina (twice), Ecuador, Lebanon, Suriname (twice) and Zambia – were all rated a low speculative grade at the beginning of the year prior to default, with an average rating of ‘CCC’. Indeed, one of this year’s three sovereign downgrades saw Suriname’s rating return to ‘RD’ for the second time in three months due to non-payment of $ 49.8 million of rescheduled external debt service.

Pockets of stress following the increase in external borrowing by emerging-market (EM) sovereigns could lead to further missed payments, with smaller and low-rated frontier markets most exposed to rising US bond yields. Distressed Debt Exchanges (DDE) are also possible, for example via the G20 Common Framework (CF) for Debt Treatments beyond the Debt Service Suspension Initiative.

Ethiopia’s downgrade to ‘CCC’ in February this year reflected its intention to use the G20 CF, which raised the possibility of a DDE via restructuring of debt to private-sector creditors.

The prospect of increased IMF financing could incentivise a small number of countries at high risk of debt distress to restructure under the G20 CF.

No developed market (DM) sovereigns defaulted in 2020, and the majority of downgrades were EM sovereigns (six DM sovereigns were downgraded). Notwithstanding their huge fiscal responses to the pandemic, DMs enjoy advantages over EMs in their financing capacity and structural credit strengths, as well as historically low debt service costs reflecting extraordinarily accommodative monetary policy. EMs contributed all 11 of 2020’s multiple sovereign downgrades of individual issuers.