Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday, 28 June 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Maria Abi-Habib

The New York Times: Every time Sri Lanka’s President, Mahinda Rajapaksa, turned to his Chinese allies for loans and assistance with an ambitious port project, the answer was yes.

Yes, though feasibility studies said the port wouldn’t work. Yes, though other frequent lenders like India had refused. Yes, though Sri Lanka’s debt was ballooning rapidly under Rajapaksa.

Over years of construction and renegotiation with China Harbour Engineering Company, one of Beijing’s largest state-owned enterprises, the Hambantota Port Development Project distinguished itself mostly by failing, as predicted. With tens of thousands of ships passing by along one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes, the port drew only 34 ships in 2012.

And then the port became China’s.

Rajapaksa was voted out of office in 2015, but Sri Lanka’s new Government struggled to make payments on the debt he had taken on. Under heavy pressure and after months of negotiations with the Chinese, the Government handed over the port and 15,000 acres of land around it for 99 years in December.

The transfer gave China control of territory just a few hundred miles off the shores of a rival, India, and a strategic foothold along a critical commercial and military waterway.

The case is one of the most vivid examples of China’s ambitious use of loans and aid to gain influence around the world — and of its willingness to play hardball to collect.

The debt deal also intensified some of the harshest accusations about President Xi Jinping’s signature Belt and Road Initiative: that the global investment and lending program amounts to a debt trap for vulnerable countries around the world, fuelling corruption and autocratic behaviour in struggling democracies.

n During the 2015 Sri Lankan elections, large payments from the Chinese port construction fund flowed directly to campaign aides and activities for Rajapaksa, who had agreed to Chinese terms at every turn and was seen as an important ally in China’s efforts to tilt influence away from India in South Asia. The payments were confirmed by documents and cash checks detailed in a government investigation seen by The New York Times.

n Though Chinese officials and analysts have insisted that China’s interest in the Hambantota Port is purely commercial, Sri Lankan officials said that from the start, the intelligence and strategic possibilities of the port’s location were part of the negotiations.

n Initially moderate terms for lending on the port project became more onerous as Sri Lankan officials asked to renegotiate the timeline and add more financing. And as Sri Lankan officials became desperate to get the debt off their books in recent years, the Chinese demands centred on handing over equity in the port rather than allowing any easing of terms.

n Though the deal erased roughly $1 billion in debt for the port project, Sri Lanka is now in more debt to China than ever, as other loans have continued and rates remain much higher than from other international lenders.

Rajapaksa and his aides did not respond to multiple requests for comment, made over several months, for this article. Officials for China Harbour also would not comment.

Estimates by the Sri Lankan Finance Ministry paint a bleak picture: This year, the government is expected to generate $14.8 billion in revenue, but its scheduled debt repayments, to an array of lenders around the world, come to $12.3 billion.

“John Adams said infamously that a way to subjugate a country is through either the sword or debt. China has chosen the latter,” said Brahma Chellaney, an analyst who often advises the Indian government and is affiliated with the Center for Policy Research, a think tank in New Delhi.

Indian officials, in particular, fear that Sri Lanka is struggling so much that the Chinese Government may be able to dangle debt relief in exchange for its military’s use of assets like the Hambantota Port — though the final lease agreement forbids military activity there without Sri Lanka’s invitation.

“The only way to justify the investment in Hambantota is from a national security standpoint — that they will bring the People’s Liberation Army in,” said Shivshankar Menon, who served as India’s foreign secretary and then its national security adviser as the Hambantota Port was being built.

An engaged ally

The relationship between China and Sri Lanka had long been amenable, with Sri Lanka an early recogniser of Mao’s Communist government after the Chinese Revolution. But it was during a more recent conflict — Sri Lanka’s brutal 26-year civil war with ethnic Tamil separatists — that China became indispensable.

Rajapaksa, who was elected in 2005, presided over the last years of the war, when Sri Lanka became increasingly isolated by accusations of human rights abuses. Under him, Sri Lanka relied heavily on China for economic support, military equipment and political cover at the United Nations to block potential sanctions.

The war ended in 2009, and as the country emerged from the chaos, Rajapaksa and his family consolidated their hold. At the height of Rajapaksa’s tenure, the President and his three brothers controlled many Government ministries and around 80% of total Government spending. Governments like China negotiated directly with them.

So when the President began calling for a vast new port development project at Hambantota, his sleepy home district, the few roadblocks in its way proved ineffective.

From the start, officials questioned the wisdom of a second major port, in a country a quarter the size of Britain and with a population of 22 million, when the main port in the capital was thriving and had room to expand. Feasibility studies commissioned by the government had starkly concluded that a port at Hambantota was not economically viable.

“They approached us for the port at the beginning, and Indian companies said no,” said Menon, the former Indian foreign secretary. “It was an economic dud then, and it’s an economic dud now.”

But Rajapaksa green-lighted the project, then boasted in a news release that he had defied all caution — and that China was on board.

The Sri Lanka Ports Authority began devising what officials believed was a careful, economically sound plan in 2007, according to an official involved in the project. It called for a limited opening for business in 2010, and for revenue to be coming in before any major expansion.

The first major loan it took on the project came from the Chinese government’s Export-Import Bank, or Exim, for $307 million. But to obtain the loan, Sri Lanka was required to accept Beijing’s preferred company, China Harbour, as the port’s builder, according to a United States Embassy cable from the time, leaked to WikiLeaks.

That is a typical demand of China for its projects around the world, rather than allowing an open bidding process. Across the region, Beijing’s Government is lending out billions of dollars, being repaid at a premium to hire Chinese companies and thousands of Chinese workers, according to officials across the region.

There were other strings attached to the loan, as well, in a sign that China saw strategic value in the Hambantota Port from the beginning.

Nihal Rodrigo, a former Sri Lankan foreign secretary and ambassador to China, said that discussions with Chinese officials at the time made it clear that intelligence sharing was an integral, if not public, part of the deal. In an interview with The Times, Rodrigo characterised the Chinese line as, “We expect you to let us know who is coming and stopping here.”

In later years, Chinese officials and the China Harbour company went to great lengths to keep relations strong with Rajapaksa, who for years had faithfully acquiesced to such terms.

In the final months of Sri Lanka’s 2015 election, China’s ambassador broke with diplomatic norms and lobbied voters, even caddies at Colombo’s premier golf course, to support Rajapaksa over the opposition, which was threatening to tear up economic agreements with the Chinese Government.

As the January election inched closer, large payments started to flow toward the president’s circle.

At least $7.6 million was dispensed from China Harbour’s account at Standard Chartered Bank to affiliates of Rajapaksa’s campaign, according to a document, seen by The Times, from an active internal government investigation. The document details China Harbour’s bank account number — ownership of which was verified — and intelligence gleaned from questioning of the people to whom the checks were made out.

With 10 days to go before polls opened, around $3.7 million was distributed in checks: $678,000 to print campaign T-shirts and other promotional material and $297,000 to buy supporters gifts, including women’s saris. Another $38,000 was paid to a popular Buddhist monk who was supporting Rajapaksa’s electoral bid, while two checks totalling $1.7 million were delivered by volunteers to Temple Trees, his official residence.

Most of the payments were from a subaccount controlled by China Harbour, named “HPDP Phase 2,” shorthand for Hambantota Port Development Project.

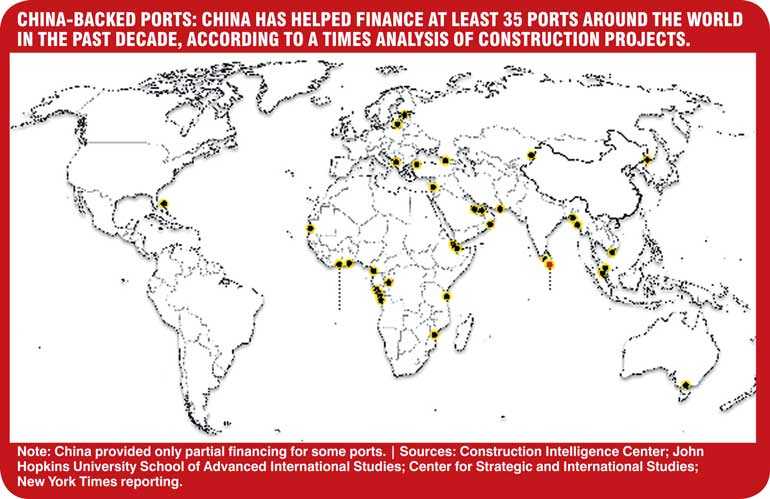

China’s network

After nearly five years of helter-skelter expansion for China’s Belt and Road Initiative across the globe, Chinese officials are quietly trying to take stock of how many deals have been done and what the country’s financial exposure might be. There is no comprehensive picture of that yet, said one Chinese economic policymaker, who like many other officials would speak about Chinese policy only on the condition of anonymity.

Some Chinese officials have become concerned that the nearly institutional graft surrounding such projects represents a liability for China, and raises the bar needed for profitability. President Xi acknowledged the worry in a speech last year, saying, “We will also strengthen international cooperation on anticorruption in order to build the Belt and Road Initiative with integrity.”

In Bangladesh, for example, officials said in January that China Harbour would be banned from future contracts over accusations that the company attempted to bribe an official at the Ministry of Roads, stuffing $100,000 into a box of tea, Government officials said in interviews. And China Harbour’s parent company, China Communications Construction Company, was banned for eight years in 2009 from bidding on World Bank projects because of corrupt practices in the Philippines.

Since the port seizure in Sri Lanka, Chinese officials have started suggesting that Belt and Road is not an open-ended government commitment to finance development across three continents.

“If we cannot manage the risk well, the Belt and Road projects cannot go far or well,” said Jin Qi, the Chairwoman of the Silk Road Fund, a large State-owned investment fund, during the China Development Forum in late March.

In Sri Lanka’s case, port officials and Chinese analysts have also not given up the view that the Hambantota Port could become profitable, or at least strengthen China’s trade capacity in the region.

Ray Ren, China Merchant Port’s representative in Sri Lanka and the head of the Hambantota Port’s operations, insisted that “the location of Sri Lanka is ideal for international trade”. And he dismissed the negative feasibility studies, saying they were done many years ago when Hambantota was “a small fishing hamlet”.

Hu Shisheng, the Director of South Asia studies at the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations, said that China clearly recognised the strategic value of the Hambantota Port. But he added: “Once China wants to exert its geostrategic value, the strategic value of the port will be gone. Big countries cannot fight in Sri Lanka — it would be wiped out.”

Although the Hambantota Port first opened in a limited way in 2010, before the Belt and Road Initiative was announced, the Chinese Government quickly folded the project into the global program.

Shortly after the handover ceremony in Hambantota, China’s State news agency released a boastful video on Twitter, proclaiming the deal “another milestone along the path of #BeltandRoad”.

A port to nowhere

The seaport is not the only grand project built with Chinese loans in Hambantota, a sparsely populated area on Sri Lanka’s south-eastern coast that is still largely overrun by jungle.

A cricket stadium with more seats than the population of Hambantota’s district capital marks the skyline, as does a large international airport — which in June lost the only daily commercial flight it had left when FlyDubai airline ended the route. A highway that cuts through the district is traversed by elephants and used by farmers to rake out and dry the rice plucked fresh from their paddies.

Rajapaksa’s advisers had laid out a methodical approach to how the port might expand after opening, ensuring that some revenue would be coming in before taking on much more debt.

But in 2009, the President had grown impatient. His 65th birthday was approaching the following year, and to mark the occasion he wanted a grand opening at the Hambantota port — including the beginning of an ambitious expansion 10 years ahead of the Port Authority’s original timeline.

Chinese labourers began working day and night to get the port ready, officials said. But when workers dredged the land and then flooded it to create the basin of the port, they had not taken into account a large boulder that partly blocked the entrance, preventing the entry of large ships, like oil tankers, that the port’s business model relied on.

Ports Authority officials, unwilling to cross the President, quickly moved ahead anyway. The Hambantota Port opened in an elaborate celebration on 18 November 2010, Rajapaksa’s birthday. Then it sat waiting for business while the rock blocked it.

China Harbour blasted the boulder a year later, at a cost of $40 million, an exorbitant price that raised concerns among diplomats and Government officials. Some openly speculated about whether the company was simply overcharging or the price tag included kickbacks to Rajapaksa.

By 2012, the port was struggling to attract ships — which preferred to berth nearby at the Colombo port — and construction costs were rising as the port began expanding ahead of schedule. The Government decreed later that year that ships carrying car imports bound for Colombo Port would instead offload their cargo at Hambantota to kick-start business there. Still, only 34 ships berthed at Hambantota in 2012, compared with 3,667 ships at the Colombo Port, according to a Finance Ministry Annual Report.

“When I came to the Government, I called the Minister of National Planning and asked for the justification of Hambantota Port,” Harsha de Silva, the State Minister for National Policies and Economic Affairs, said in an interview. “She said, ‘We were asked to do it, so we did it.’”

Determined to keep expanding the port, Rajapaksa went back to the Chinese Government in 2012, asking for $757 million.

The Chinese agreed again. But this time, the terms were much steeper.

The first loan, at $307 million, had originally come at a variable rate that usually settled above 1 or 2% after the global financial crash in 2008. (For comparison, rates on similar Japanese loans for infrastructure projects run below half a percent.)

But to secure fresh funding, that initial loan was renegotiated to a much higher 6.3% fixed rate. Rajapaksa acquiesced.

The rising debt and project costs, even as the port was struggling, handed Sri Lanka’s political opposition a powerful issue, and it campaigned heavily on suspicions about China. Rajapaksa lost the election.

The incoming Government, led by President Maithripala Sirisena, came to office with a mandate to scrutinise Sri Lanka’s financial deals. It also faced a daunting amount of debt: Under Rajapaksa, the country’s debt had increased threefold, to $44.8 billion when he left office. And for 2015 alone, a $4.68 billion payment was due at year’s end.

Signing it away

The new Government was eager to reorient Sri Lanka toward India, Japan and the West. But officials soon realised that no other country could fill the financial or economic space that China held in Sri Lanka.

“We inherited a purposefully run-down economy — the revenues were insufficient to pay the interest charges, let alone capital repayment,” said Ravi Karunanayake, who was Finance Minister during the new Government’s first year in office.

“We did keep taking loans,” he added. “A new government can’t just stop loans. It’s a relay; you need to take them until economic discipline is introduced.” The Central Bank estimated that Sri Lanka owed China about $3 billion last year. But Nishan de Mel, an economist at Verité Research, said some of the debts were off Government books and instead registered as part of individual projects. He estimated that debt owed to China could be as much as $5 billion and was growing every year. In May, Sri Lanka took a new $1 billion loan from China Development Bank to help make its coming debt payment.

Government officials began meeting in 2016 with their Chinese counterparts to strike a deal, hoping to get the port off Sri Lanka’s balance sheet and avoid outright default. But the Chinese demanded that a Chinese company take a dominant equity share in the port in return, Sri Lankan officials say — writing down the debt was not an option China would accept.

When Sri Lanka was given a choice, it was over which State-owned company would take control: either China Harbour or China Merchants Port, according to the final agreement, a copy of which was obtained by The Times, although it was never released publicly in full.

China Merchants got the contract, and it immediately pressed for more: Company officials demanded 15,000 acres of land around the port to build an industrial zone, according to two officials with knowledge of the negotiations. The Chinese company argued that the port itself was not worth the $1.1 billion it would pay for its equity — money that would close out Sri Lanka’s debt on the port.

Some Government officials bitterly opposed the terms, but there was no leeway, according to officials involved in the negotiations. The new agreement was signed in July 2017, and took effect in December.

The deal left some appearance of Sri Lankan ownership: Among other things, it created a joint company to manage the port’s operations and collect revenue, with 85% owned by China Merchants Port and the remaining 15% controlled by Sri Lanka’s Government.

But lawyers specialising in port acquisitions said Sri Lanka’s small stake meant little, given the leverage that China Merchants Port retained over board personnel and operating decisions. And the Government holds no sovereignty over the port’s land.

When the agreement was initially negotiated, it left open whether the port and surrounding land could be used by the Chinese military, which Indian officials asked the Sri Lankan Government to explicitly forbid. The final agreement bars foreign countries from using the port for military purposes unless granted permission by the government in Colombo.

That clause is there because Chinese Navy submarines had already come calling to Sri Lanka.

Strategic concerns

China had a stake in Sri Lanka’s main port as well: China Harbour was building a new terminal there, known at the time as Colombo Port City. Along with that deal came roughly 50 acres of land, solely held by the Chinese company, that Sri Lanka had no sovereignty on.

That was dramatically demonstrated toward the end of Rajapaksa’s term, in 2014. Chinese submarines docked at the harbour the same day that Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan was visiting Colombo, in what was seen across the region as a menacing signal from Beijing.

When the new Sri Lankan Government came to office, it sought assurances that the port would never again welcome Chinese submarines — of particular concern because they are difficult to detect and often used for intelligence gathering. But Sri Lankan officials had little real control.

Now, the handover of Hambantota to the Chinese has kept alive concerns about possible military use — particularly as China has continued to militarise island holdings around the South China Sea despite earlier pledges not to.

Sri Lankan officials are quick to point out that the agreement explicitly rules out China’s military use of the site. But others also note that Sri Lanka’s Government, still heavily indebted to China, could be pressured to allow it.

And, as de Silva, the State Minister for National Policies and Economic Affairs, put it, “Governments can change.”

Now, he and others are watching carefully as Rajapaksa, China’s preferred partner in Sri Lanka, has been trying to stage a political comeback. The former President’s new Opposition party swept municipal elections in February. Presidential elections are coming up next year, and general elections in 2020.

Although Rajapaksa is barred from running again because of term limits, his brother, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the former Defence Secretary, appears to be readying to take the mantle.

“It will be Mahinda Rajapaksa’s call. If he says it’s one of the brothers, that person will have a very strong claim,” said Ajith Nivard Cabraal, the Central Bank Governor under Rajapaksa’s Government, who still advises the family. “Even if he’s no longer the president, as the Constitution is structured, Mahinda will be the main power base.”

Pix credit: Adam Dean for The New York Times

(Reporting was contributed by Keith Bradsher and Sui-Lee Wee from Beijing, and Mujib Mashal and Dharisha Bastians from Sri Lanka.)