Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Friday, 5 March 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Sarah Repucci and Amy Slipowitz

https://freedomhouse.org: As a lethal pandemic, economic and physical insecurity, and violent conflict ravaged the world in 2020, democracy’s defenders sustained heavy new losses in their struggle against authoritarian foes, shifting the international balance in favour of tyranny. Incumbent leaders increasingly used force to crush opponents and settle scores, sometimes in the name of public health, while beleaguered activists—lacking effective international support—faced heavy jail sentences, torture, or murder in many settings.

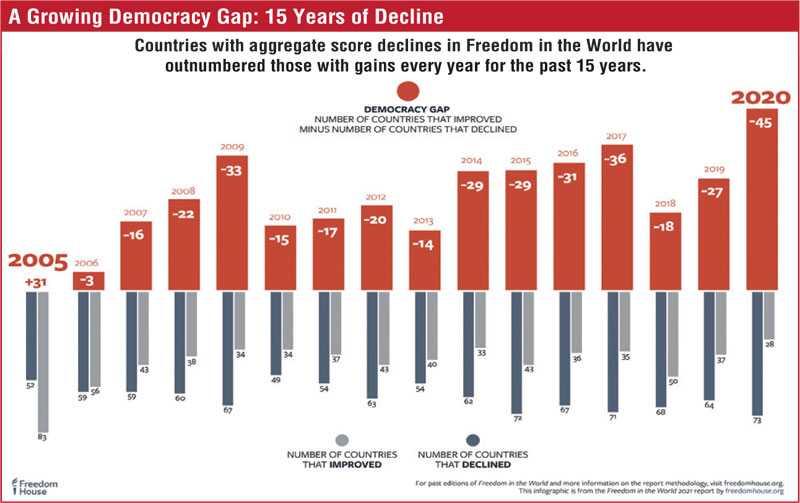

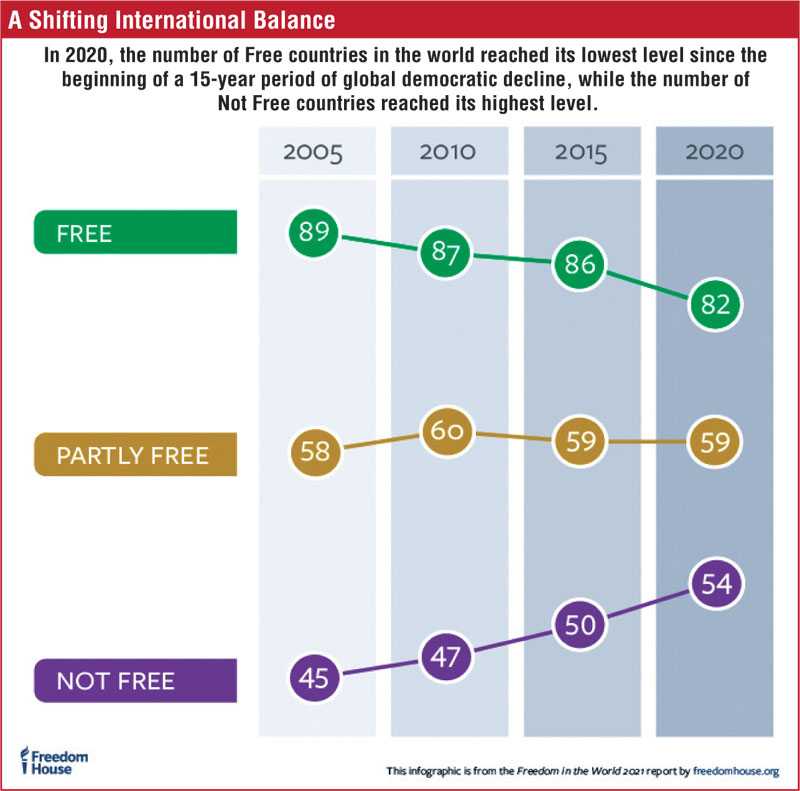

These withering blows marked the 15th consecutive year of decline in global freedom. The countries experiencing deterioration outnumbered those with improvements by the largest margin recorded since the negative trend began in 2006. The long democratic recession is deepening.

The impact of the long-term democratic decline has become increasingly global in nature, broad enough to be felt by those living under the cruellest dictatorships, as well as by citizens of long-standing democracies. Nearly 75% of the world’s population lived in a country that faced deterioration last year. The ongoing decline has given rise to claims of democracy’s inherent inferiority. Proponents of this idea include official Chinese and Russian commentators seeking to strengthen their international influence while escaping accountability for abuses, as well as antidemocratic actors within democratic states who see an opportunity to consolidate power. They are both cheering the breakdown of democracy and exacerbating it, pitting themselves against the brave groups and individuals who have set out to reverse the damage.

The malign influence of the regime in China, the world’s most populous dictatorship, was especially profound in 2020. Beijing ramped up its global disinformation and censorship campaign to counter the fallout from its cover-up of the initial coronavirus outbreak, which severely hampered a rapid global response in the pandemic’s early days. Its efforts also featured increased meddling in the domestic political discourse of foreign democracies, transnational extensions of rights abuses common in mainland China, and the demolition of Hong Kong’s liberties and legal autonomy. Meanwhile, the Chinese regime has gained clout in multilateral institutions such as the UN Human Rights Council, which the United States abandoned in 2018, as Beijing pushed a vision of so-called non-interference that allows abuses of democratic principles and human rights standards to go unpunished while the formation of autocratic alliances is promoted.

As COVID-19 spread during the year, governments across the democratic spectrum repeatedly resorted to excessive surveillance, discriminatory restrictions on freedoms like movement and assembly, and arbitrary or violent enforcement of such restrictions by police and non-state actors. Waves of false and misleading information, generated deliberately by political leaders in some cases, flooded many countries’ communication systems, obscuring reliable data and jeopardising lives. While most countries with stronger democratic institutions ensured that any restrictions on liberty were necessary and proportionate to the threat posed by the virus, a number of their peers pursued clumsy or ill-informed strategies, and dictators from Venezuela to Cambodia exploited the crisis to quash opposition and fortify their power.

The expansion of authoritarian rule, combined with the fading and inconsistent presence of major democracies on the international stage, has had tangible effects on human life and security, including the frequent resort to military force to resolve political disputes. As long-standing conflicts churned on in places like Libya and Yemen, the leaders of Ethiopia and Azerbaijan launched wars last year in the regions of Tigray and Nagorno-Karabakh, respectively, drawing on support from authoritarian neighbours Eritrea and Turkey and destabilising surrounding areas. Repercussions from the fighting shattered hopes for tentative reform movements in both Armenia, which clashed with the Azerbaijani regime over Nagorno-Karabakh, and Ethiopia.

India, the world’s most populous democracy, dropped from Free to Partly Free status in Freedom in the World 2021. The government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and its state-level allies continued to crack down on critics during the year, and their response to COVID-19 included a ham-fisted lockdown that resulted in the dangerous and unplanned displacement of millions of internal migrant workers. The ruling Hindu nationalist movement also encouraged the scapegoating of Muslims, who were disproportionately blamed for the spread of the virus and faced attacks by vigilante mobs. Rather than serving as a champion of democratic practice and a counterweight to authoritarian influence from countries such as China, Modi and his party are tragically driving India itself toward authoritarianism.

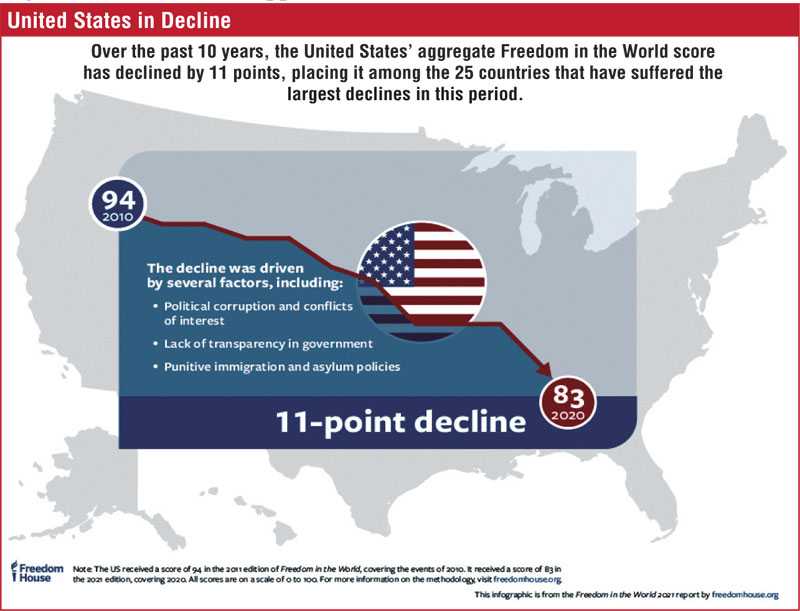

The parlous state of US democracy was conspicuous in the early days of 2021 as an insurrectionist mob, egged on by the words of outgoing president Donald Trump and his refusal to admit defeat in the November election, stormed the Capitol building and temporarily disrupted Congress’s final certification of the vote. This capped a year in which the administration attempted to undermine accountability for malfeasance, including by dismissing inspectors general responsible for rooting out financial and other misconduct in government; amplified false allegations of electoral fraud that fed mistrust among much of the US population; and condoned disproportionate violence by police in response to massive protests calling for an end to systemic racial injustice. But the outburst of political violence at the symbolic heart of US democracy, incited by the president himself, threw the country into even greater crisis. Notwithstanding the inauguration of a new president in keeping with the law and the constitution, the United States will need to work vigorously to strengthen its institutional safeguards, restore its civic norms, and uphold the promise of its core principles for all segments of society if it is to protect its venerable democracy and regain global credibility.

The widespread protest movements of 2019, which had signalled the popular desire for good governance the world over, often collided with increased repression in 2020. While successful protests in countries such as Chile and Sudan led to democratic improvements, there were many more examples in which demonstrators succumbed to crackdowns, with oppressive regimes benefiting from a distracted and divided international community. Nearly two dozen countries and territories that experienced major protests in 2019 suffered a net decline in freedom the following year.

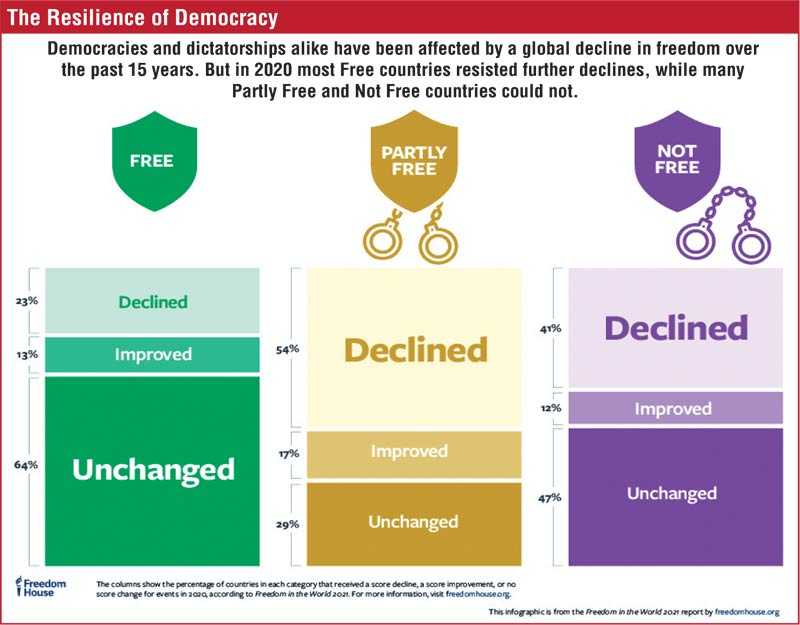

Although Freedom in the World’s better-performing countries had been in retreat for several years, in 2020 it was struggling democracies and authoritarian states that accounted for more of the global decline. The proportion of Not Free countries is now the highest it has been in the past 15 years. On average, the scores of these countries have declined by about 15% during the same period. At the same time, the number of countries worldwide earning a net score improvement for 2020 was the lowest since 2005, suggesting that the prospects for a change in the global downward trend are more challenging than ever. With India’s decline to Partly Free, less than 20% of the world’s population now lives in a Free country, the smallest proportion since 1995. As repression intensifies in already unfree environments, greater damage is done to their institutions and societies, making it increasingly difficult to fulfil public demands for freedom and prosperity under any future government.

The enemies of freedom have pushed the false narrative that democracy is in decline because it is incapable of addressing people’s needs. In fact, democracy is in decline because its most prominent exemplars are not doing enough to protect it. Global leadership and solidarity from democratic states are urgently needed. Governments that understand the value of democracy, including the new administration in Washington, have a responsibility to band together to deliver on its benefits, counter its adversaries, and support its defenders. They must also put their own houses in order to shore up their credibility and fortify their institutions against politicians and other actors who are willing to trample democratic principles in the pursuit of power. If free societies fail to take these basic steps, the world will become ever more hostile to the values they hold dear, and no country will be safe from the destructive effects of dictatorship.

The shifting international balance

Over the past year, oppressive and often violent authoritarian forces tipped the international order in their favour time and again, exploiting both the advantages of nondemocratic systems and the weaknesses in ailing democracies. In a variety of environments, flickers of hope were extinguished, contributing to a new global status quo in which acts of repression went unpunished and democracy’s advocates were increasingly isolated.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), faced with the danger that its authoritarian system would be blamed for covering up and thus exacerbating the COVID-19 pandemic, worked hard to convert the risk into an opportunity to exert influence. It provided medical supplies to countries that were hit hard by the virus, but it often portrayed sales as donations and orchestrated propaganda events with economically dependent recipient governments. Beijing sometimes sought to shift blame to the very countries it claimed to be helping, as when Chinese state media suggested that the coronavirus had actually originated in Italy. Throughout the year, the CCP touted its own authoritarian methods for controlling the contagion, comparing them favourably with democracies like the United States while studiously ignoring the countries that succeeded without resorting to major abuses, most notably Taiwan. This type of spin has the potential to convince many people that China’s censorship and repression are a recipe for effective governance rather than blunt tools for entrenching political power.

Beyond the pandemic, Beijing’s export of antidemocratic tactics, financial coercion, and physical intimidation have led to an erosion of democratic institutions and human rights protections in numerous countries. The campaign has been supplemented by the regime’s moves to promote its agenda at the United Nations, in diplomatic channels, and through worldwide propaganda that aims to systematically alter global norms. Other authoritarian states have joined China in these efforts, even as key democracies abandoned allies and their own values in foreign policy matters. As a result, the mechanisms that democracies have long used to hold governments accountable for violations of human rights standards and international law are being weakened and subverted, and even the world’s most egregious violations, such as the large-scale forced sterilisation of Uighur women, are not met with a well-coordinated response or punishment.

In this climate of impunity, the CCP has run roughshod over Hong Kong’s democratic institutions and international legal agreements. The territory has suffered a massive decline in freedom since 2013, with an especially steep drop since mass prodemocracy demonstrations were suppressed in 2019 and Beijing tightened its grip in 2020. The central government’s imposition of the National Security Law in June erased almost overnight many of Hong Kong’s remaining liberties, bringing it into closer alignment with the system on the mainland. The Hong Kong government itself escalated its use of the law early in 2021 when more than 50 prodemocracy activists and politicians were arrested, essentially for holding a primary and attempting to win legislative elections that were ultimately postponed by a year; they face penalties of up to life in prison. In November the Beijing and Hong Kong governments had colluded to expel four prodemocracy members from the existing Legislative Council, prompting the remaining 15 to resign in protest. These developments reflect a dramatic increase in the cost of opposing the CCP in Hong Kong, and the narrowing of possibilities for turning back the authoritarian tide.

The use of military force by authoritarian states, another symptom of the global decay of democratic norms, was on display in Nagorno-Karabakh last year. New fighting erupted in September when the Azerbaijani regime, with decisive support from Turkey, launched an offensive to settle a territorial dispute that years of diplomacy with Armenia had failed to resolve. At least 6,500 combatants and hundreds of civilians were killed, and tens of thousands of people were newly displaced. Meaningful international engagement was absent, and the war only stopped when Moscow imposed a peacekeeping plan on the two sides, fixing in place the Azerbaijani military’s territorial gains but leaving many other questions unanswered.

The fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh has had spillover effects for democracy. In addition to strengthening the rule of Azerbaijan’s authoritarian president, Ilham Aliyev, the conflict threatens to destabilise the government in Armenia. A rare bright spot in a region replete with deeply entrenched authoritarian leaders, Armenia has experienced tentative gains in freedom since mass antigovernment protests erupted in 2018 and citizens voted in a more reform-minded government. But Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s capitulation in the war sparked a violent reaction among some opponents, who stormed the parliament in November and physically attacked the speaker. Such disorder threatens the country’s hard-won progress, and could set off a chain of events that draws Armenia closer to the autocratic tendencies of its neighbours.

Ethiopia had also made democratic progress in recent years, as new Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed lifted restrictions on opposition media and political groups and released imprisoned journalists and political figures. However, persistent ethnic and political tensions remained. In July 2020, a popular ethnic Oromo singer was killed, leading to large protests in the Oromia Region that were marred by attacks on non-Oromo populations, a violent response by security forces, and the arrest of thousands of people, including many opposition figures. The country’s fragile gains were further imperilled after the ruling party in the Tigray Region held elections in September against the will of the federal authorities and labeled Abiy’s government illegitimate. Tigrayan forces later attacked a military base, leading to an overwhelming response from federal forces and allied ethnic militias that displaced tens of thousands of people and led to untold civilian casualties. In a dark sign for the country’s democratic prospects, the government enlisted military support from the autocratic regime of neighbouring Eritrea, and national elections that were postponed due to the pandemic will now either take place in the shadow of civil conflict or be pushed back even further.

In Venezuela, which has experienced a dizzying 40-point score decline over the last 15 years, some hope arose in 2019 when opposition National Assembly leader Juan Guaidó appeared to present a serious challenge to the rule of dictator Nicolás Maduro. The opposition named Guaidó as interim president under the constitution, citing the illegitimacy of the presidential election that kept Maduro in power, and many democratic governments recognised his status. In 2020, however, as opponents of the regime continued to face extrajudicial execution, enforced disappearances, and arbitrary detention, Maduro regained the upper hand. Tightly controlled National Assembly elections went forward despite an opposition boycott, creating a new body with a ruling party majority. The old opposition-led legislature hung on in a weakened state, extending its own term as its electoral legitimacy ebbed away.

Belarus emerged as another fleeting bright spot in August, when citizens unexpectedly rose up to dispute the fraudulent results of a deeply flawed election. Alyaksandr Lukashenka’s repressive rule had previously been taken for granted, but for a few weeks the protests appeared to put him on the defensive as citizens awakened to their democratic potential despite brutal crackdowns, mass arrests, and torture. By the start of 2021, however, despite ongoing resistance, Lukashenka remained in power, and protests, more limited in scale, continued to be met with detentions. Political rights and civil liberties have become even more restricted than before, and democracy remains a distant aspiration.

In fact, Belarus was far from the only place where the promise of increased freedom raised by mass protests eventually curdled into heightened repression. Of the 39 countries and territories where Freedom House noted major protests in 2019, 23 experienced a score decline for 2020—a significantly higher share than countries with declines represented in the world at large. In settings as varied as Algeria, Guinea, and India, regimes that protests had taken by surprise in 2019 regained their footing, arresting and prosecuting demonstrators, passing newly restrictive laws, and in some cases resorting to brutal crackdowns, for which they faced few international repercussions.

The fall of India from the upper ranks of free nations could have a particularly damaging impact on global democratic standards. Political rights and civil liberties in the country have deteriorated since Narendra Modi became prime minister in 2014, with increased pressure on human rights organisations, rising intimidation of academics and journalists, and a spate of bigoted attacks, including lynchings, aimed at Muslims. The decline only accelerated after Modi’s reelection in 2019. Last year, the government intensified its crackdown on protesters opposed to a discriminatory citizenship law and arrested dozens of journalists who aired criticism of the official pandemic response.

Judicial independence has also come under strain; in one case, a judge was transferred immediately after reprimanding the police for taking no action during riots in New Delhi that left over 50 people, mostly Muslims, dead. In December, Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, approved a law that prohibits forced religious conversion through interfaith marriage, which critics fear will effectively restrict interfaith marriage in general; authorities have already arrested a number of Muslim men for allegedly forcing Hindu women to convert to Islam. Amid the pandemic the government imposed an abrupt COVID-19 lockdown in the spring, which left millions of migrant workers in cities without work or basic resources. Many were forced to walk across the country to their home villages, facing various forms of mistreatment along the way. Under Modi, India appears to have abandoned its potential to serve as a global democratic leader, elevating narrow Hindu nationalist interests at the expense of its founding values of inclusion and equal rights for all.

To reverse the global shift toward authoritarian norms, democracy advocates working for freedom in their home countries will need robust solidarity from like-minded allies abroad.

The eclipse of US leadership

The final weeks of the Trump presidency featured unprecedented attacks on one of the world’s most visible and influential democracies. After four years of condoning and indeed pardoning official malfeasance, ducking accountability for his own transgressions, and encouraging racist and right-wing extremists, the outgoing president openly strove to illegally overturn his loss at the polls, culminating in his incitement of an armed mob to disrupt Congress’s certification of the results. Trump’s actions went unchecked by most lawmakers from his own party, with a stunning silence that undermined basic democratic tenets. Only a serious and sustained reform effort can repair the damage done during the Trump era to the perception and reality of basic rights and freedoms in the United States.

The year leading up to the assault on the Capitol was fraught with other episodes that threw the country into the global spotlight in a new way. The politically distorted health recommendations, partisan infighting, shockingly high and racially disparate coronavirus death rates, and police violence against protesters advocating for racial justice over the summer all underscored the United States’ systemic dysfunctions and made American democracy appear fundamentally unstable. Even before 2020, Trump had presided over an accelerating decline in US freedom scores, driven in part by corruption and conflicts of interest in the administration, resistance to transparency efforts, and harsh and haphazard policies on immigration and asylum that made the country an outlier among its Group of Seven peers. But President Trump’s attempt to overturn the will of the American voters was arguably the most destructive act of his time in office. His drumbeat of claims—without evidence—that the electoral system was ridden by fraud sowed doubt among a significant portion of the population, despite what election security officials eventually praised as the most secure vote in US history. Nationally elected officials from his party backed these claims, striking at the foundations of democracy and threatening the orderly transfer of power.

Though battered, many US institutions held strong during and after the election process. Lawsuits challenging the result in pivotal states were each thrown out in turn by independent courts. Judges appointed by presidents from both parties ruled impartially, including the three Supreme Court justices Trump himself had nominated, upholding the rule of law and confirming that there were no serious irregularities in the voting or counting processes. A diverse set of media outlets broadly confirmed the outcome of the election, and civil society groups investigated the fraud claims and provided evidence of a credible vote. Some Republicans spoke eloquently and forcefully in support of democratic principles, before and after the storming of the Capitol. Yet it may take years to appreciate and address the effects of the experience on Americans’ ability to come together and collectively uphold a common set of civic values.

The exposure of US democracy’s vulnerabilities has grave implications for the cause of global freedom. Rulers and propagandists in authoritarian states have always pointed to America’s domestic flaws to deflect attention from their own abuses, but the events of the past year will give them ample new fodder for this tactic, and the evidence they cite will remain in the world’s collective memory for a long time to come. After the Capitol riot, a spokesperson from the Russian foreign ministry stated, “The events in Washington show that the US electoral process is archaic, does not meet modern standards, and is prone to violations.” Zimbabwe’s president said the incident “showed that the US has no moral right to punish another nation under the guise of upholding democracy.” For most of the past 75 years, despite many mistakes, the United States has aspired to a foreign policy based on democratic principles and support for human rights. When adhered to, these guiding lights have enabled the United States to act as a leader on the global stage, pressuring offenders to reform, encouraging activists to continue their fight, and rallying partners to act in concert. After four years of neglect, contradiction, or outright abandonment under Trump, President Biden has indicated that his administration will return to that tradition. But to rebuild credibility in such an endeavor and garner the domestic support necessary to sustain it, the United States needs to improve its own democracy. It must strengthen institutions enough to survive another assault, protect the electoral system from foreign and domestic interference, address the structural roots of extremism and polarisation, and uphold the rights and freedoms of all people, not just a privileged few.

Everyone benefits when the United States serves as a positive model, and the country itself reaps ample returns from a more democratic world. Such a world generates more trade and fairer markets for US goods and services, as well as more reliable allies for collective defense. A global environment where freedom flourishes is more friendly, stable, and secure, with fewer military conflicts and less displacement of refugees and asylum seekers. It also serves as an effective check against authoritarian actors who are only too happy to fill the void.

The long arm of COVID-19

Since it spread around the world in early 2020, COVID-19 has exacerbated the global decline in freedom. The outbreak exposed weaknesses across all the pillars of democracy, from elections and the rule of law to egregiously disproportionate restrictions on freedoms of assembly and movement. Both democracies and dictatorships experienced successes and failures in their battle with the virus itself, though citizens in authoritarian states had fewer tools to resist and correct harmful policies. Ultimately, the changes precipitated by the pandemic left many societies—with varied regime types, income levels, and demographics—in worse political condition; with more pronounced racial, ethnic, and gender inequalities; and vulnerable to long-term effects.

Transparency was one of the hardest-hit aspects of democratic governance. National and local officials in China assiduously obstructed information about the outbreak, including by carrying out mass arrests of internet users who shared related information. In December, citizen journalist Zhang Zhan was sentenced to four years in prison for her reporting from Wuhan, the initial epicentre. The Belarusian government actively downplayed the seriousness of the pandemic to the public, refusing to take action, while the Iranian regime concealed the true toll of the virus on its people. Some highly repressive governments, including those of Turkmenistan and Nicaragua, simply ignored reality and denied the presence of the pathogen in their territory. More open political systems also experienced significant transparency problems. At the presidential level and in a number of states and localities, officials in the United States obscured data and actively sowed misinformation about the transmission and treatment of the coronavirus, leading to widespread confusion and the politicisation of what should have been a public health matter. Similarly, Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro repeatedly downplayed the harms of COVID-19, promoted unproven treatments, criticised subnational governments’ health measures, and sowed doubt about the utility of masks and vaccines.

Freedom of personal expression, which has experienced the largest declines of any democracy indicator since 2012, was further restrained during the health crisis. In the midst of a heavy-handed lockdown in the Philippines under President Rodrigo Duterte, the authorities stepped up harassment and arrests of social media users, including those who criticised the government’s pandemic response. Cambodia’s authoritarian Prime Minister, Hun Sen, presided over the arrests of numerous people for allegedly spreading false information linked to the virus and criticising the state’s performance. Governments around the world also deployed intrusive surveillance tools that were often of dubious value to public health and featured few safeguards against abuse.

But beyond their impact in 2020, official responses to COVID-19 have laid the groundwork for government excesses that could affect democracy for years to come. As with the response to the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, when the United States and many other countries dramatically expanded their surveillance activities and restricted due process rights in the name of national security, the COVID-19 pandemic has triggered a shift in norms and the adoption of problematic legislation that will be challenging to reverse after the virus has been contained.

In Hungary, for example, a series of emergency measures allowed the government to rule by decree despite the fact that coronavirus cases were negligible in the country until the fall. Among other misuses of these new powers, the government withdrew financial assistance from municipalities led by opposition parties. The push for greater executive authority was in keeping with the gradual concentration of power that Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has been orchestrating over the past decade. An indicative move came in December, when the pliant parliament approved constitutional amendments that transferred public assets into the hands of institutions headed by ruling-party loyalists, reduced independent oversight of government spending, and pandered to the ruling party’s base by effectively barring same-sex couples from adopting children.

In Algeria, President Abdelmadjid Tebboune, who had recently taken office through a tightly controlled election after longtime authoritarian leader Abdelaziz Bouteflika resigned under public pressure, banned all forms of mass gatherings in March. Even as other restrictions were eased in June, the prohibition on assembly remained in place, and authorities stepped up arrests of activists associated with the prodemocracy protest movement. Many of the arrests were based on April amendments to the penal code, which had been adopted under the cover of the COVID-19 response. The amended code increased prison sentences for defamation and criminalised the spread of false information, with higher penalties during a health or other type of emergency—provisions that could continue to suppress critical speech in the future.

Indonesia turned to the military and other security forces as key players in its pandemic response. Multiple military figures were appointed to leading positions on the country’s COVID-19 task force, and the armed services provided essential support in developing emergency hospitals and securing medical supplies. In recent years, observers have raised concerns about the military’s growing influence over civilian governance, and its heavy involvement in the health crisis threatened to accelerate this trend. Meanwhile, restrictions on freedoms of expression and association have worsened over time, pushing the country’s scores deeper into the Partly Free range.

In Sri Lanka, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa dissolved the parliament in early March, intending to hold elections the following month. The pandemic delayed the vote, however, giving Rajapaksa the opportunity to rule virtually unchecked and consolidate power through various ministerial appointments. After his party swept the August elections, the new parliament approved constitutional amendments that expanded presidential authority, including by allowing Rajapaksa to appoint electoral, police, human rights, and anticorruption commissions. The changes also permitted the chief executive to hold ministerial positions and dissolve the legislature after it has served just half of its term.

The public health crisis is causing a major economic crisis, as countries around the world fall into recession and millions of people are left unemployed. Marginalised populations are bearing the brunt of both the virus and its economic impact, which has exacerbated income inequality, among other disparities. In general, countries with wider income gaps have weaker protections for basic rights, suggesting that the economic fallout from the pandemic could have harmful implications for democracy. The global financial crisis of 2008–09 was notably followed by political instability and a deepening of the democratic decline.

The COVID-19 pandemic is not the only current global emergency that has the potential to hasten the erosion of democracy. The effects of climate change could have a similar long-term impact, with mass displacement fuelling conflict and more nationalist, xenophobic, and racist policies. Numerous other, less predictable crises could also surface, including new health emergencies. Democracy’s advocates need to learn from the experience of 2020 and prepare for emergency responses that respect the political rights and civil liberties of all people, including the most marginalised.

The resilience of democracy

A litany of setbacks and catastrophes for freedom dominated the news in 2020. But democracy is remarkably resilient, and has proven its ability to rebound from repeated blows.

A prime example can be found in Malawi, which made important gains during the year. The Malawian people have endured a low-performing democratic system that struggled to contain a succession of corrupt and heavy-handed leaders. Although mid-2019 national elections that handed victory to the incumbent president were initially deemed credible by local and international observers, the count was marred by evidence that Tipp-Ex correction fluid was used to alter vote tabulation sheets. The election commission declined to call for a new vote, but opposition candidates took the case to the constitutional court. The court resisted bribery attempts and issued a landmark ruling in February 2020, ordering fresh elections. Opposition presidential candidate Lazarus Chakwera won the June rerun vote by a comfortable margin, proving that independent institutions can hold abuse of power in check. While Malawi is a country of 19 million people, the story of its election rerun has wider implications, as courts in other African states have asserted their independence in recent years, and the nullification of a flawed election—for only the second time in the continent’s history—will not go unnoticed.

Taiwan overcame another set of challenges in 2020, suppressing the coronavirus with remarkable effectiveness and without resorting to abusive methods, even as it continued to shrug off threats from an increasingly aggressive regime in China. Taiwan, like its neighbours, benefited from prior experience with SARS, but its handling of COVID-19 largely respected civil liberties. Early implementation of expert recommendations, the deployment of masks and other protective equipment, and efficient contact-tracing and testing efforts that prioritised transparency—combined with the country’s island geography—all helped to control the disease. Meanwhile, Beijing escalated its campaign to sway global opinion against Taiwan’s government and deny the success of its democracy, in part by successfully pressuring the World Health Organisation to ignore early warnings of human-to-human transmission from Taiwan and to exclude Taiwan from its World Health Assembly. Even before the virus struck, Taiwanese voters defied a multipronged, politicised disinformation campaign from China and overwhelmingly reelected incumbent president Tsai Ing-wen, who opposes moves toward unification with the mainland.

More broadly, democracy has demonstrated its adaptability under the unique constraints of a world afflicted by COVID-19. A number of successful elections were held across all regions and in countries at all income levels, including in Montenegro, and in Bolivia, yielding improvements. Judicial bodies in many settings, such as The Gambia, have held leaders to account for abuses of power, providing meaningful checks on the executive branch and contributing to slight global gains for judicial independence over the past four years. At the same time, journalists in even the most repressive environments like China sought to shed light on government transgressions, and ordinary people from Bulgaria to India to Brazil continued to express discontent on topics ranging from corruption and systemic inequality to the mishandling of the health crisis, letting their leaders know that the desire for democratic governance will not be easily quelled.

The Biden administration has pledged to make support for democracy a key part of US foreign policy, raising hopes for a more proactive American role in reversing the global democratic decline. To fulfil this promise, the president will need to provide clear leadership, articulating his goals to the American public and to allies overseas. He must also make the United States credible in its efforts by implementing the reforms necessary to address considerable democratic deficits at home. Given many competing priorities, including the pandemic and its socioeconomic aftermath, President Biden will have to remain steadfast, keeping in mind that democracy is a continuous project of renewal that ultimately ensures security and prosperity while upholding the fundamental rights of all people.

Democracy today is beleaguered but not defeated. Its enduring popularity in a more hostile world and its perseverance after a devastating year are signals of resilience that bode well for the future of freedom.

(Source: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2021/democracy-under-siege)