Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Tuesday, 10 July 2018 00:37 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

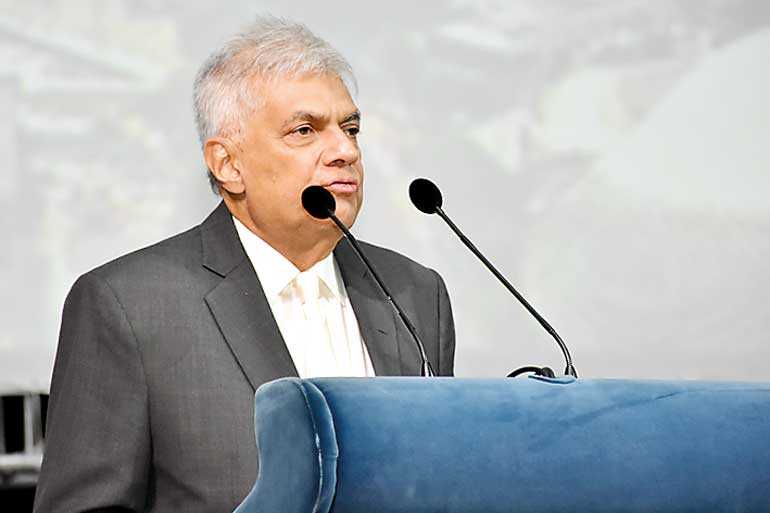

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe delivering the keynote address at the summit in Singapore

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe with his Singaporean counterpart Lee Hsien Loong. Ministers Malik Samarawickrama, Sajith Premadasa, Mrs. Wickremesinghe, other members of the Lankan delegation and Singapore Minister for Communications and Information S. Iswaran and other officials are also present

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe with his Singaporean counterpart Lee Hsien Loong. Ministers Malik Samarawickrama, Sajith Premadasa, Mrs. Wickremesinghe, other members of the Lankan delegation and Singapore Minister for Communications and Information S. Iswaran and other officials are also present

Building liveable and sustainable cities calls for greater integration with global chains, strengthening local governments and ensuring social inclusivity, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe said yesterday.

Delivering the keynote address at the World Cities Summit, International Water Week and Clean Environment Summit in Singapore, Wickremesinghe noted that large-scale migration to cities has provided new challenges to Governments and policy makers to grow liveable cities that use resources, especially water, sustainably.

“I use the term “Anthropocene” to describe the times we live in, because it is an era indelibly shaped by human activity. One such incredibly influential activity has been our large-scale migration from the countryside to the city; thus the “Anthropocene” is fundamentally marked by urbanisation. Data from the World Bank shows that in 2017, 54.7% of the world’s population – that is 4.1 billion people – lived in urban areas,” he said.

The Prime Minister noted that this change has taken place because around the world, urbanisation has been a transformative trend that has propelled economic growth. By bringing people and enterprises together, large cities have become centres of industrialisation and modernisation. They have reaped the benefits of economies of agglomeration. When firms and workers cluster together there is improved productivity and job creation. Mega-cities have gone one step further: they have become highly productive centres which connect workers and businesses with global markets. Cities, therefore, have become hubs of wealth creation, attracting waves of people with opportunities for advancement not available in their villages, he pointed out.

“The Beijing- Tianjin- Qinhuangdao corridor has a population of over 100 million. I can see a future where a sprawl of mega urban centres stretches from Beijing to Bangkok to Jakarta to Mumbai. Although cities across Asia are growing apace, only three (Singapore, Tokyo, and Kobe) are in the top 50 of the Mercer Quality of Life index. Colombo was the highest ranked South Asian city, but still only stood at 137 out of 231 cities. At least 15 Asian cities are in the bottom 50 of this ranking. Our challenge, as leaders, is to make these Asian cities liveable for the present and the future. The sustainable development of our globe depends on whether we succeed or fail.”

Given its importance, the task of building liveable and sustainable cities require integrating with global supply chains, social inclusivity, and access to new and old ecosystem services. The Prime Minister also outlined plans by the Government to develop Colombo into a Megapolis to improve living standards of nine million people, and would include a light railway system with elevated railways, elevated highways, a multi-modal transport hub, the development of old waterways, and three LNG plants.

“It will encompass a Logistics City, a Forest City, and an Aero City. We will aim for maximum liveability by implementing sewerage and solid waste projects, an Eco Zone, and Riverine Buffer Zone Development,” he said. “For Sri Lanka or any other country to deal with these challenges, we need to politically and financially revitalise and empower local governments. The biggest issue in the management of mega-cities is that they involve many levels of Government and Local Authorities. Political power in many of our countries were distributed between the Central Government, the Provinces and the Local Authorities in the last century when concepts such as mega-cities and global connectivity had not even been thought of. Given that we will now have to exercise these powers for completely different objectives in a completely different environment, it is inevitable then that we must reconsider the structure of our local governments.

“As we continue to face these traditional challenges, we must also be aware of the new developments in urbanisation, which will characterise the Anthropocene in the 21st Century. One characteristic of high-density living is the opportunity for a wide variety of people-to-people interactions.”

However in recent times, Wickremesinghe stated, that human communication has been completely overshadowed by a new phenomenon. Driven by sophistication in electronic sensors for information capture, new generation high-speed internet for rapid information transmission or receipt, and artificial intelligence for making judgments based on the analysis of massive volumes of data, “things” are now communicating, both with each other and with humans. Around 35 billion “things” are connected to the Internet today. Cisco Systems estimates that this will rise to 50 billion by 2020, far exceeding the number of humans connected to the internet, estimated at around 4 billion persons using 25 billion apps.

“This can have an immense impact on the way we live in and govern cities. Consider something seemingly simple, like ‘smart’ streetlights. A 2015 study by the Northeast Group estimated that cities around the world would invest $64 billion in LED and ‘smart’ streetlights by 2025, along with sensors, communications, and analytics software that would make their street lighting infrastructure ‘smarter.’

“We must recognise that our cities cannot stand in isolation: they depend on their hinterland for the provision of the ecosystem services. In Sri Lanka water has become the most critical of these eco-system services. The challenge for the ancient Kingdoms was to manage the vast volumes of water made available by the Monsoons. The rainwater was conserved in artificial ponds and man-made reservoirs for drinking and irrigation, which remain serviceable to this day. In recent years, possibly due to global climate change, while Sri Lanka’s annual precipitation is falling, the frequency of extreme events is increasing. This is further aggravated by the rising population and industrialisation of the southwest. The result has been disastrous. Lives, livelihoods, and property have been lost with disturbing regularity through floods and landslides. Water today is a foe. In fact, the 2004 tsunami made the sea our enemy as well.”