Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Wednesday, 26 February 2020 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Shailendree Wickrama Adittiya

From Greta Thunberg to Australian forest fires to cold snaps in North America and the systematic destruction of the Amazon rainforest, the climate and impact of climate change has never been as hot button a topic as it is now.

One of the largest contributors towards this impending climate crisis is the textiles industry, which has traditionally scored heavily in terms of carbon dioxide emissions and water wastage. It is unsurprising therefore that sustainable fashion has gained popularity over the years, with Sri Lanka in particular keen to make headway in the field – from clothing products made out of upcycled waste to using bio-degradable and ethically sourced dyes, Sri Lankan brands have embraced sustainable fashion in many ways.

And in BananaTex, Sri Lanka’s textiles sector may be on to its next winning idea. An initiative by the Sri Lanka Institute of Textile and Apparel (SLITA) in collaboration with the Industry and Commerce Ministry and the Moratuwa University, BananaTex uses eco-friendly technology to turn banana stems – a waste product – into fibre and then yarn.

With over 29 varieties in the country, banana is one of the most widely cultivated and consumed fruits in Sri Lanka. And be it Ambul, Kolikuttu, Seeni Kesel or Nethra Palam, banana cultivation is carried out throughout the year. But while there remains several uses for the various parts of the plant, banana stems are often discarded as waste. It is this agri-waste product that BananaTex uses to create yarn, which can then be used for clothing, thus boosting the country’s textile industry.

"Everything is imported. And yet, Sri Lankan garments are world-recognised and world-famous – SLITA Director General Robert V. Peries"

One of the largest exports in the country, textiles and garments amounted to over $ 5.317 billion from January to November last year, a 5.2% change from 2018, according to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) External Sector Performance Report December 2019.

That said, according to SLITA Director General Robert V. Peries, Sri Lanka does not have any raw material, whether it is cotton or synthetic yarn.

“Everything is imported,” revealed Peries. “And yet, Sri Lankan garments are world-recognised and world-famous.”

It is for this reason that initiatives like BananaTex are vital for industry growth. As SLITA Technologist and member of the project’s steering committee A.C.S.I. Mumthas said, the lack of a fibre base in Sri Lanka is a major concern. However, the boost in the sustainable product market is pushing the industry to look for natural fibres.

“Even with a small marginal cost, they are accepting these natural fibres because they are bio-degradable and have zero carbon footprint,” said Mumthas, noting that investing in the project and necessary machinery could be a huge value addition to local products.

"Even with a small marginal cost, they are accepting these natural fibres because they are bio-degradable and have zero carbon footprint – SLITA Technologist A.C.S.I. Mumthas"

According to Mumthas, BananaTex is a group effort and the steering committee should be credited equally. This includes individuals from the Industry and Commerce Ministry, SLITA, as well as Moratuwa University.

The project is a result of the National Research and Development Framework (NRDF), which has 10 focus areas. Under textiles, the subcategory textile material innovation (fibre, yarn, accessories) states that developing “new methods of production: Sustainable natural fibres and regenerated fibres based on agricultural waste such as banana, pineapple, plant materials” is a relevant intervention.

“The Government has introduced initiatives to encourage research culture but the problem is that our people have some barriers to conducting research,” added Mumthas.

Nevertheless, one of the objectives of SLITA is to conduct research in relevant areas, which was one of the main reasons as to why Mumthas and SLITA Assistant Technologist Subashini Balakrishnan began looking into the feasibility of turning agricultural waste products into sustainable natural fibres – in the end choosing banana, as it is the most feasible and accessible.

“Farmers pay to get rid of stems so we thought of utilising it so the farmers get an extra income, while it also generates job opportunities and contributes to the country’s revenue,” Mumthas explained. She added that 10 of the 29 varieties of banana in the country were chosen for use following successful feasibility studies.

This though is not a new area of research. “There are a few small scale industries that make fibre out of banana and make handicrafts, particularly in Jaffna and Embilipitiya,” noted Peries.

However, none of the research on creating banana yarn, as opposed to fibre, has progressed to the level as BananaTex. The process used to create this involves a number of machines which SLITA has, with the process of banana stems being weaved into fabric on a handloom machine observable at the SLITA laboratory itself.

"Farmers pay to get rid of stems so we thought of utilising it so the farmers get an extra income, while it also generates job opportunities and contributes to the country’s revenue – Mumthas"

SLITA has 80 different courses, ranging from certificates to higher national diplomas, and their ISO certified testing laboratory conducts 115 different tests, including performance tests, water resistance tests, and safety tests. SLITA also provides technical and project consultancy, for both the State and private sectors.

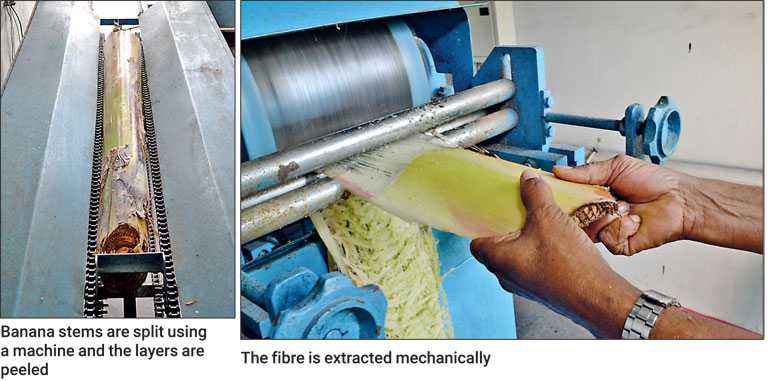

While fabric made of banana yarn is not produced on a commercial scale at the SLITA laboratory, they were able to modify their machinery to produce banana yarn. The process has multiple steps and starts with the obtaining of stems, which the team said cultivators are more than happy to part with. The stems are then split using a machine and the layers are peeled.

“These layers are subjected to the fibre decorticating machine, from which you can get fibre out. You have to then dry it,” Mumthas said, adding that a simple treatment using bio-enzymes is done to see if the yarn can be spun.

“Those spinnable fibres are blended with cotton and then we manufacture the yarn. That is the process.”

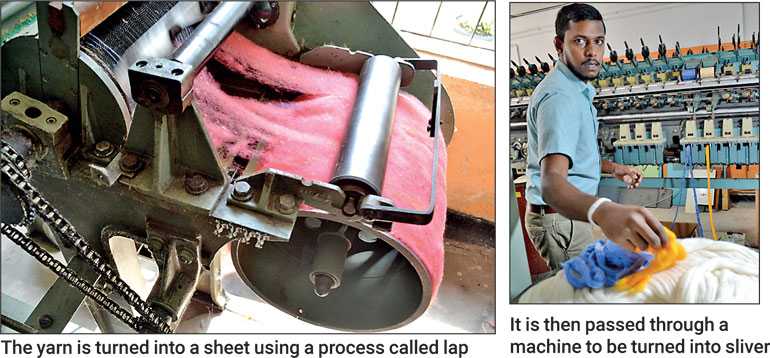

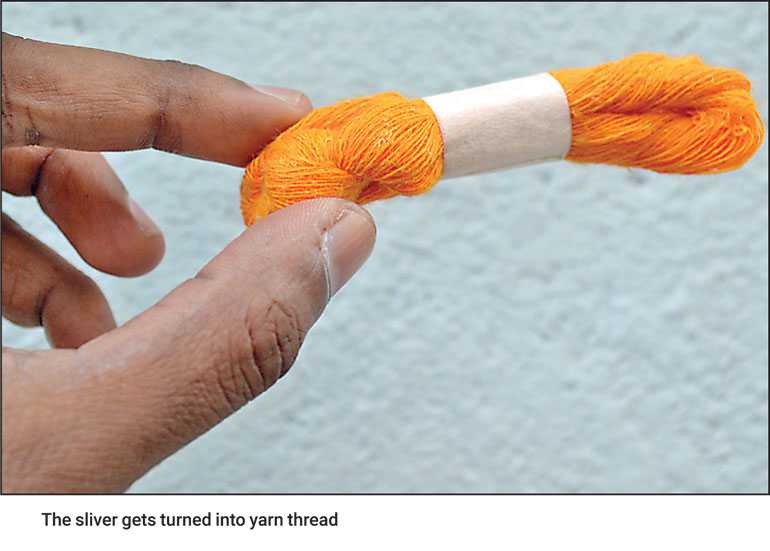

Using a process called lap, the yarn is turned into a sheet, which is then passed through a machine to be turned into sliver. The sliver is what gets turned into yarn thread, which is then used with cotton thread to weave fabric on a handloom machine. According to Sitha, who operates the machine, weaving a yard of fabric takes around half an hour.

“The cotton yarn is placed lengthways and the banana yarn is placed across. It’s with this mix that fabric is spun,” she said.

A collection made out of banana fabric, designed by SLITA Visiting Lecturer in processing Gayani Dulanga, was displayed at the Intex South Asia 2018 exhibition. The inspiration for the collection, from designs to colours, came from various stages of the banana plant.

"If farmers can extract fibres out from the stem, they can generate more than 500 per annum – Mumthas"

While banana yarn and cotton mixed fabric may seem like the final product of the research conducted, the committee is not ready to put a stop to their efforts just yet. According to Mumthas, the research is still progressing and the committee aims to manufacture a 100% banana yarn fabric.

But this doesn’t mean that this step in their research is not of interest to the textile industry. According to Peries, an Invitation for Expression of Interest has been called by the Industry and Commerce Ministry.

“As this project was done by the Government and we undertook the research, we have the responsibility to transfer the technology,” explained Peries.

Mumthas added that interest in banana fibre and yarn has grown following various awareness sessions conducted by the team, and they are currently developing a means by which to transfer the technology in their possession. Indeed, it is this inability to transfer the technology that has seen the technology on banana fibre extraction available in the Philippines remain inaccessible to Sri Lanka.

In a positive development, Mumthas shared that the process of distributing banana fibre extraction machines has now begun.

“If farmers can extract fibres out from the stem, they can generate more than $ 500 per annum,” she added.

As it stands, there is a demand for banana fibre, especially when it comes to making crafts to be sold to foreign markets, but there is a lack of supply. In order to make banana yarn or fabric commercially viable, investment in spinning machines is essential.

With the right amount of investment and development, banana yarn can hopefully go from simply being a research project conducted by SLITA in collaboration with the Industry and Commerce Ministry and Moratuwa University, to an eco-friendly sustainable product that boosts Sri Lanka’s textile industry.

Pix by Shehan Gunasekara