Sunday Mar 08, 2026

Sunday Mar 08, 2026

Tuesday, 1 January 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By P. Samarasiri

The monetary policy press release on 28 December informed of policy rates unchanged at 8% and 9% at levels decided on 13 November. No public briefing on new policy decision was held although announced.

Information reveals highly-subsidised policy interest rates maintained although monetary conditions further deteriorated since the last policy decision requiring more hikes in policy rates.

Therefore, the rising demand for liquidity for outflow of foreign investments and import credit continued due to low interest rates subsidised by the CB’s money printing. The only solution now available with the MB to stabilise the currency turmoil and high demand for liquidity is the further hikes in policy rates in a short time. This is simple economics.

For example, currency turmoil in 2000 was resolved by raising policy interest rates to 20%-23% (by 10%-11%) by March 2001 from January 2000. Several direct controls also were imposed. However, already delayed hikes in policy rates and extended injection of the liquidity cause headwinds, given financial tightening in global markets, pending another two rates hikes by the US Fed and policy tightening by the European Central Bank in 2019.

Recent policy actions

The present economic instability is a result of irrational phase of tightening of the monetary policy since January 2016 as follows.

MB’s policy failure

In July 2017, the MB reintroduced direct bond placements to control interest rates within the monetary policy, despite it being a bond issuance window, where no information is released to the public as in the past. The CB continued to heavily subscribe to weekly issuances of Treasury bills outside primary auctions as in the past practice to control yield rates/money market rates without any regard to developing currency turmoil. The MB thought that interest rates with earlier hikes (without any valid reasons) were already high and kept them unchanged until November in view of depressing economic growth and low inflation (measured by weather and subsidy-driven cost of living index).

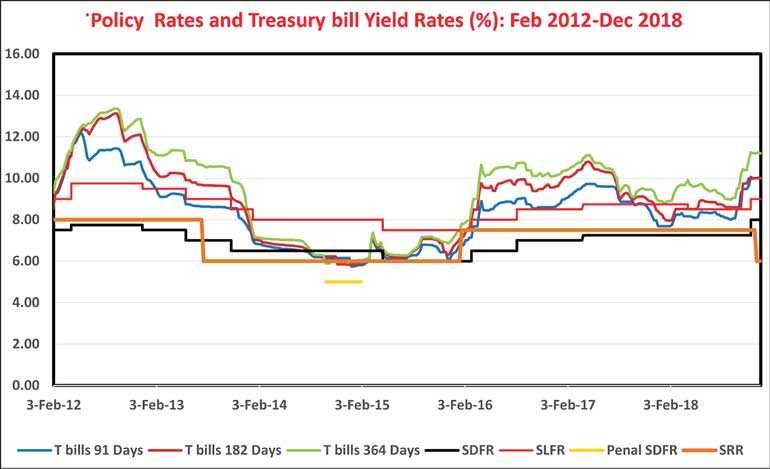

Therefore, the present currency turmoil has got its way and the MB could not control both exchange rates and market interest rates (see Chart), despite wide duties stipulated in the Monetary Law Act.

The MB continues with the current model of monetary policy based on targeting overnight inter-bank interest rates and liquidity to satisfy bank/money dealers without any research on its connection/transmission to liquidity and credit needs of sectors of the wider economy such as exports, agriculture and SMEs.

It appears that the MB has now given up the exchange rate stability (depreciation more than 18%) but follows subsidised interest rates to satisfy liquidity needs of the inter-bank market and government securities market. However, the economic growth continues to depress while actual inflationary pressures are built up from excessive currency depreciation, money printing and concessions-based budget deficits (expected in next two years on account of pending elections).

Therefore, risks of stagflation (low growth with high inflation) in next one to two years are seen high. If the MB had not unnecessarily tightened the monetary policy in 2016 and 2017, it would have the policy space to handle the present turmoil at the early stage in 2018.

The Monetary Board is responsible for the economic and price stability of the country. It can’t wash its hands by passing the blame to the Government for the instability. Evading statements like “growth enhancing structural reforms are carried out within a coherent and transparent framework, rather than relying on unsustainable short-term monetary and fiscal stimulus, which leads to overheating of the economy” as stated in the November press release and “the need for implementing broad based structural reforms without further delay” as stated in December press release are meaningless as the MB itself has failed in its public duties.

The Government must be finally accountable for the economic loss to the public due to the duty failure of the MB. How the Government of India handled its ideological Central Bank since September 2018 is a good lesson.

(The writer is a former public servant as a Deputy Governor of the CB and a chairman and a member of six public boards who authored five economics and financial/banking books published by the CB and more than 50 published articles.)