Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Wednesday, 27 March 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Alexis Calla

Early this year, our investment committee members went on the road to present our 2019 Outlook to our clients across Asia, Africa, the Middle-East and Europe, as we do every year. One of the key messages that we have constantly communicated over the years is the importance of diversification. While we get the sense that some of our investors have been heeding this message, it is also clear that some have yet to be convinced.

But this year, in conversations with some clients we introduced the idea of ‘emotional’ investment returns, highlighting that the way you implement diversification can have an impact on how your investment returns affect you. This can, in turn, impact your future investment decisions which could be detrimental to your long term financial returns. This idea clearly resonated with them and we decided to share it more broadly.

One of my favourite books is Daniel Kahneman’s ‘Thinking Fast and Slow’. Kahneman is a Nobel Prize winner for his research (with Amos Tversky) into behavioural biases. One of their theories is ‘prospect theory’, which states that ‘the pain of losing is 2 times greater than the pleasure of winning’. Let’s examine the recent performance of a couple of different asset classes in recent times to demonstrate the importance of this finding.

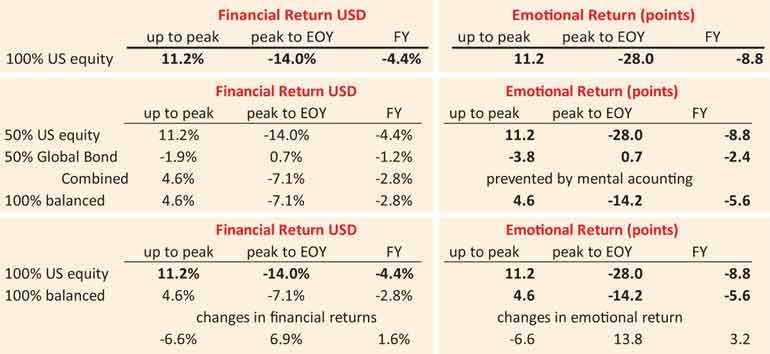

One of the most popular asset classes in 2018 was US equities, which rose 11.2% from its start of the year level of 5212 to its 5794 peak-level in September, before falling 14.0% from the peak to its year-end level of 4984. From a ‘classic financial’ point of view, if this was the person’s only investment (let us say $ 10,000), the loss would have been 4.4%. Not ideal, but hardly the end of the world. However, from an ‘emotional’ point of view it was probably a lot worse. Taking Kahneman’s 2:1 emotional cost/benefit ratio into account, the investor would have experienced 11.2 gain in ‘emotional points’ followed by a 28 points loss (2 multiply by 14), before arriving at a net loss of 8.8 ‘emotional points’. What an emotional roller coaster!

But what about an investor who got intrigued by our call for diversification?

There are two potential ways to achieve this. One way is to invest equally in two different funds. The second is to invest in a fund that has a 50:50 split between the two asset classes. While they are financially equivalent (assuming the fund manager invests in the same underlying assets), emotionally they can be very different.

To work fully, financially as well as emotionally, diversification requires investors to look at their investments as a pool and not as a set of separate items. Another Nobel Prize winner, Richard Thaler, established that many of us have a tendency called ‘mental accounting’ that often prevent us from looking at things in totality. What this means is we all have the tendency to look at each individual line of an investment portfolio. This can influence us to make sub-optimal decisions.

Developing the above analysis further, let’s take the example of an investor who decided to split her US equity investment, allocating $ 5,000 to global bonds. On this second investment, she would have made a loss of 1.9% (loss of 3.8 ‘emotional points’) through to the peak in the US stock market and then a gain of 0.7% (gain of 0.7 ‘emotional points’) in the remainder of the year for a net loss of 2.4 ‘emotional points’ over the year. The combination of the two investments would have been a 4.6% gain through to the peak in the US stock market and then a loss of 7.1% in the remainder of the year for a net loss of 2.8% over the year. But ‘mental accounting’ would have prevented our investor from aggregating ‘emotional’ returns, the equity allocation remaining a painful 8.8 ‘emotional points’ loss. [Note: A loss is 2 times more emotionally impactful than an equivalent gain]

However, for the investor who decided to invest $ 10,000 in one fund that diversified across both US equities and global bonds, her return would have been 4.6% (4.6 ‘emotional points’) through September and then a loss of 7.1% (-14.2 ‘emotional points’) in the remainder of the year for a net -5.6 ‘emotional points’ loss.

As you can see, the financial return is clearly the same at each point, but the ‘emotional’ returns can be very different if the investor mentally accounts for each individual investment.

When using a balanced product, the reduction in the ‘emotional’ pain during the equity market fall (-14.2 points vs -28 points) far outweighs the loss of ‘emotional’ gain up to the peak period (4.6 points vs 11.2 points).

The risk of ignoring the investor’s ‘emotional’ pain would be so great that they would sell what is hurting them. Not only could this distract them from their long-term objectives, but in this instance, it would also have meant selling equities just before the strong rally we subsequently saw since the turn of the year (+11.8%).

Helping our clients make less biased investment decisions is one of our key objectives at Standard Chartered Bank. The above academic research, together with our day-to-day experience with clients, suggests investors should allocate a significant portion of their investments to core diversified holdings as we believe this will help them manage their emotions and stay on track when it comes to their long-term financial goals.

(The writer is Chief Investment Officer at Standard Chartered Bank.)