Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Saturday, 9 January 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A trekker in the Knuckles Mountain Range, which is named after its fist-shaped peaks – Courtesy Moonstone Expeditions

Women pick tea in the mountainous region of central Sri Lanka– Photo by Rob McKenzie

The Knuckles Mountain Range – Photo by Rob McKenzie

By Rob McKenzie

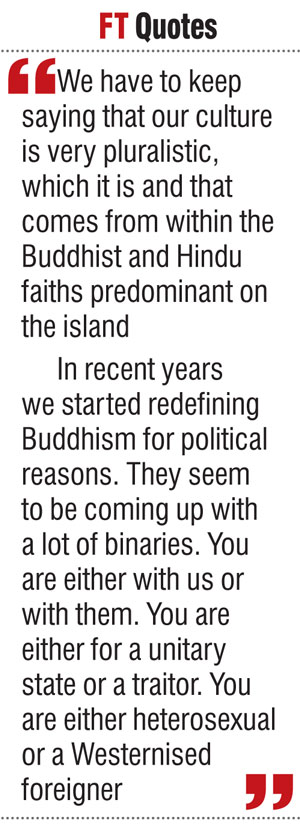

At the end of the first day, we stop at a house for tea. This house in the hills is solid but humble. Simple wooden furniture. A South Indian movie on the television set. A picture of heroes or gods. Peeling paint – no surprise, given how much rain falls here.

The Tamil owner goes down the steps to the pantry. His adult daughter walks gingerly as she crosses the main room, also towards the pantry. It was she who would be making our dinner that night.

Ravi leans in. “She is totally blind,” he says. “She has never seen the world.”

But you can ask her about anything, he marvels, and she can tell you all about it.

We’re in the Knuckles Mountain Range of central Sri Lanka. The range is so named because of its oddly shaped mountains, the result of millions of years of faulting and folding, which do in some cases resemble a fist’s knuckles. Ravi is the man arranging my three-day hike for Moonstone Expeditions, a tour company founded in 2013 by Iain Mackay, formerly an officer in the British army.

This land is effortlessly green. After eight years in Abu Dhabi, I’m caught off guard by the Sri Lankan lushness. Lightning flares on my first night, in the taxi on the airport road into Colombo, and I ponder how it looks like the whole sky is being electrocuted. Which, in plain fact, is pretty much what lightning does. I had taken the literal and rendered it metaphorical. Clearly, I have lost my bearings for green, wet places.

My guide for the trek is Asela. His family lives on a farm in this area. Asela is 19. His father was a policeman before becoming a farmer. Asela’s favourite subject in school was dance. He laughs a lot – for example, when he tells me how short his girlfriend is – and he has an impressive knowledge of the flora and fauna, something I see a lot of during my trip.

Flora: jackfruit, breadfruit, grapefruit, guava, papaya, mango (the trees have surprisingly thick trunks), cloud trees, pine trees, bamboo, tea, coffee, cacao, cardamom plants, dwarf morning glory, African tulip, a hanging white flower that Asela says is known as angel’s frock, orchids, water lilies, wild sunflower, wild orange, long pepper and tamarind.

Fauna: a red-vented bulbul, a hanging parrot, an Oriental magpie-robin (boldly dressed in glossy black and white), a black eagle, a purple-faced leaf monkey (racing along the treetops), a macaque, a mongoose, crabs, skinks, a rhino-horned lizard, a green lizard, porcupines (or at least a spot where two fought; the dust of the pathway is messed up, and I grab a stray quill as a keepsake), beehives and leeches.

The leeches are interesting. They find a spot on a grassy or gravelly path, and when they smell something blood-filled approaching, they lift their heads in the air and sway – like little cobras, like question marks, like they’re saying hello, like they’re fans at a football game trying to get a wave started. When I stop to look at some sight – a macaque atop a high rock, say, his scratchy trill a message to the troop that intruders are afoot – a bunch of the leeches start racing towards me, wiggling their abdomens up and down like caterpillars, all these question marks converging on the answer to: “What’s for lunch?”

On the first afternoon, a leech sneaks under my trouser leg, and spends the afternoon fattening himself on the blood beneath my left calf. Asela removes the leech by spraying it with a mix of Dettol and water that he keeps handy in a big plastic water bottle with a hole poked into the lid.

The blood keeps flowing for quite a while, as leech saliva contains anticoagulants. What fascinates me is the clot that forms afterwards. It isn’t like a normal stoppage. It’s thick like tar or sealant, as if it’s made of marrow.

We cover about 30 kilometres in three days, which is about 15 hours walking in total. We walk on village footpaths, forest trails, half-paved roads and rough stone staircases that bisect the many switchbacks.

It’s not the distance that’s challenging, but rather the afternoon downpours that soak us and make the paths slippery, and the ups and downs as we cross the hills. I completed a comparable hike in Kyrgyzstan two years ago, and that one, though a day briefer, was much more arduous, because of the higher altitude. My Sri Lankan hike caps out at about 1,750 metres; in Kyrgyzstan, we were at 2,600 metres.

The Knuckles hike is mostly in forest, but we pass through villages, and run into people now and then. We see barefoot women picking tea leaves, some by hand, and one with a scythe. We see a mother combing her daughter’s hair on their veranda; and soon after, two schoolgirls, maybe 6 years old, with yellow ribbons streaming from their pigtails. We pass by a silver-haired woman using her scythe to cut stray branches of wild sunflower that had broken off in high winds the night before; this will be firewood.

Where are the men? If it’s the women who are occupying the foreground, the men are in the background, labouring – building a bridge, filling a lorry with gravel to improve the roads, or out in the rice paddies. And at the end of the hike, suddenly behind us is a broadly smiling boy of 9 or 10 in a saffron robe – a Buddhist monk.

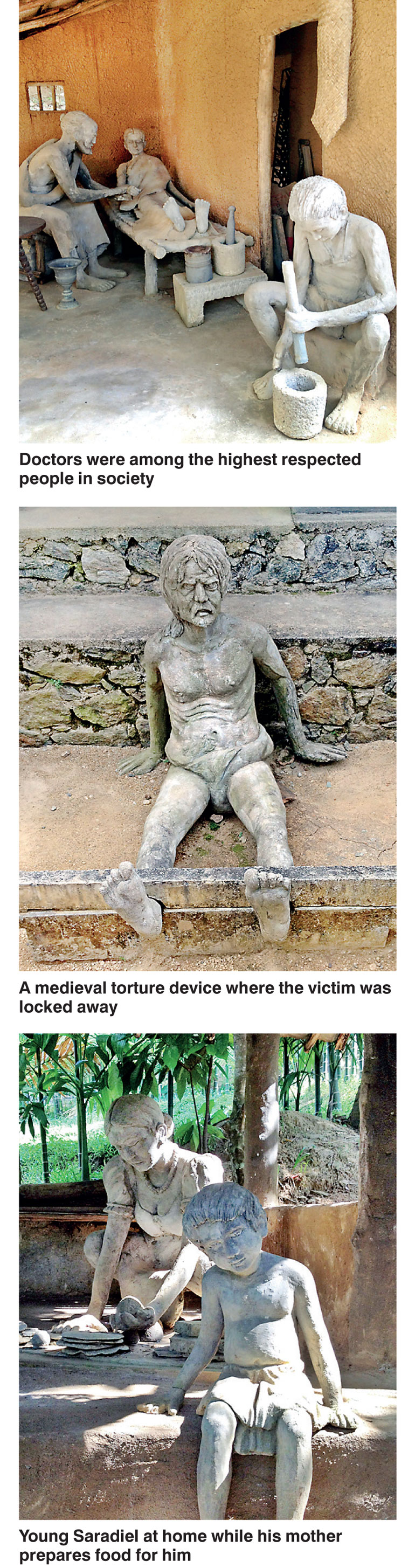

I’m a little unwell for most of the trek – probably airplane flu. Ravi notices this on the first day as we drive through Kandy, not far from the trailhead. After I seem less than enthused when he points out the prison fort where the British hanged Sura Saradiel, the Robin Hood of Ceylon, Ravi asks me if everything is all right. I tell him I’m not feeling so hot and could probably use some medicine if possible.

In lieu of a pharmacy, we stop at a roadside shop. Ravi buys sachets of Ayurvedic tea, which I drink in hot water with a dollop of honey. The medicine’s ingredients start with coriander and pass through cumin and vishnukranthi (derived from the above-mentioned dwarf morning glory), finishing at cane sugar.

The drink helps, and quickly. But by the end of the second night of the hike, with all the rain, I’m pretty stuffy again. The campsite master, Dixon, makes a simple tea with fresh-cut ginger that clears me up and also warms me, which is useful given that all my clothes are in varying states of dampness from the rain. I finish my tea, sit on a wooden bench, nuzzle a shy little dog who had followed us all day, and read a book on logic.

For dinner, Dixon makes chicken with noodles, fresh pineapple, and potatoes in a milky coconut sauce. I dig into the potatoes, and he brings more. I say I like the potatoes, and out comes a third serving.

Breakfast is also restorative: bananas, pineapple, roti, a fried egg, coconut sambal (with dried fish and chillies), and one store-bought ingredient: a jar of wood-apple jam.

The last day’s walk is the easiest, being mostly downhill. I had slept fitfully, but I don’t feel tired: perhaps it’s the effects of the novelty of mountain air in my lungs.

A day earlier, while the rain falls all through that first afternoon, and I huff and puff as one uphill switchback gives way to another uphill switchback, I ask myself: “Why am I doing this? It leaves me drained – what’s the point?”

That evening, after our tea in the Tamil family’s house, I lay in front of my tent, rest my head on my backpack and look out over the misty hills of the cloud forest as daylight fades away. I fall into a nap to the sounds of crickets and frogs, and realise that’s why I do this: to fall asleep surrounded by nature to the sounds of crickets and frogs. (The National)