Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Saturday, 9 April 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

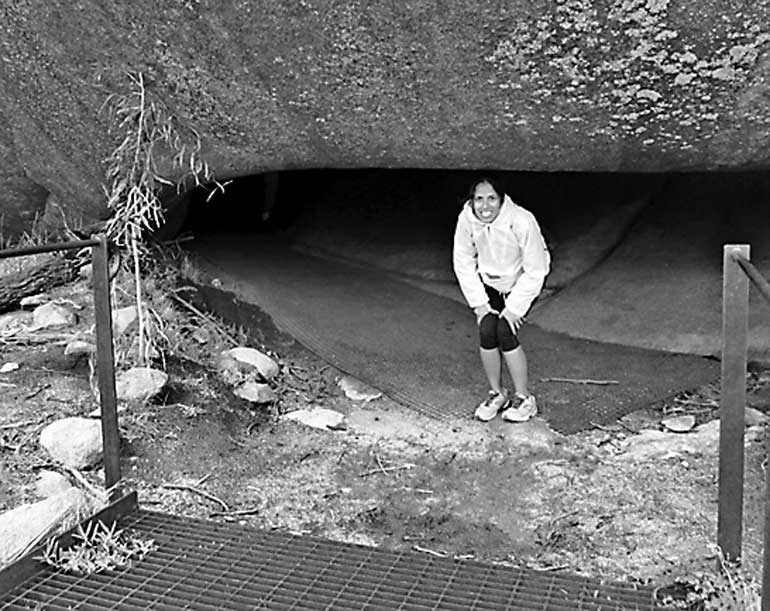

Steel-way leading to the cave

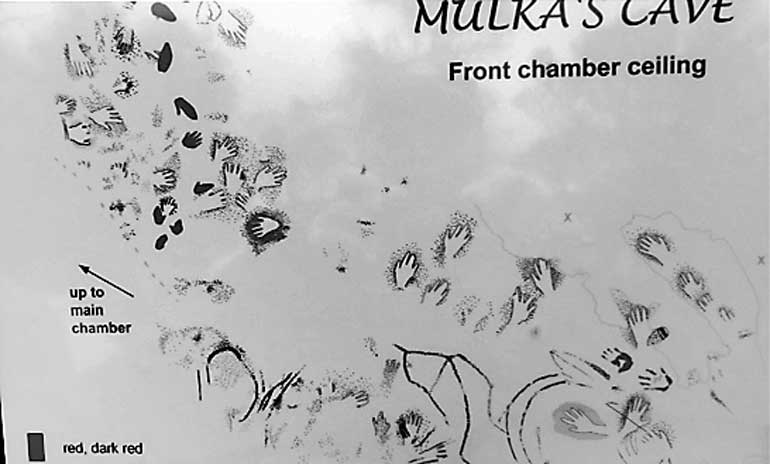

Hand stencils in the cave

The Aboriginal people in Australia are believed to have the oldest continuous living cultures in the world. Among them are the Noongar people who lived in caves and made a living by hunting and trapping animals like kangaroos and wallabies, by fishing using spears and fishing traps, and by gathering edible wild plants.

The Aboriginal people in Australia are believed to have the oldest continuous living cultures in the world. Among them are the Noongar people who lived in caves and made a living by hunting and trapping animals like kangaroos and wallabies, by fishing using spears and fishing traps, and by gathering edible wild plants.

As most other indigenous cultures, the Noongar people also had own beliefs and they saw the arrival of Europeans as the returning of deceased people. Thy called them ‘djanga’ meaning ‘white spirits’. This was because their white complexion reminded the Noongar of corpses and the unclean odour of early 19th century Europeans was said to resemble the dead. Another fact was that the ships arrived from the west, the setting sun location of the soul in traditional beliefs.

In Heyden area (described in last week’s column) are caves where these people have lived several centuries ago. Among them is one particular cave which is a major tourist attraction. Called the ‘Mulka’, it comes from an Aboriginal legend associated with the cave.

A highlight of the cave are the many hand stencils believed to be those of adults and children.

The stencils are made by placing the hand on the rock, then blowing over it with pigment. When the hand is removed, a negative impression remains. Hand stencils were made for many reasons, but most commonly, they were used as a form of signature left by those who had rights to the area.

There are also some line paintings which are often outlined with the finger or with a fibrous twig dipped in crushed ochre mixed with water.

A display panel relates the legend connected with the Mulka cave: Mulka was the illegitimate son of a woman who fell in love with a man to whom marriage was forbidden. As a result, Mulka was born with crossed eyes. Even though he grew up to be an extraordinarily strong man of colossal height, his crossed eyes prevented him from aiming a spear accurately and becoming a successful hunter.

Out of frustration he turned to catching and eating human children and he became the terror of the district. He lived in Mulka’s cave where the impressions of his hands can still be seen much higher than those of an ordinary man.

His mother became increasingly concerned for Mulka and when she scolded him for his anti-social behaviour, he turned on his mother and killed her. This disgraced him even more and he fled the cave. Aboriginal people were outraged by Mulka and set out to track down the man who had flouted all the rules. They finally caught him 156km south of Hyden. Because he did not deserve a proper ritual burial, they left his body for the ants – a grim warning to those who break the law.

Anthropologists say that for countless millennia Aboriginal culture has been governed by complex laws and customs that have passed down through generations. It has been an ‘oral tradition’ where nothing had been written down. They have a highly-developed pattern of telling stories and verbal transmission of accumulated wisdom. The Mulka legend forms part of this pattern.

‘Wrong-way marriage’ was deeply frowned upon and for a variety of cultural and physical (genetic) reasons it has long been clearly set out through relationship of various ‘skin groups’ as to whom one could marry. Anthropologists conclude that marrying outside of this accepted pattern threatened the core of stability that helped Aboriginal communities survive and indeed thrive.

Thus one interpretation of the Mulka legend could be that it is a story of the dangers of ‘wrong-way marriage’ intended as a warning that such unions produce ‘evil’ outcomes and must be avoided at all cost. It also cautions the children not to move away from the campfire at night since they can be caught by evil giants like Mulka.