Tuesday Jan 20, 2026

Tuesday Jan 20, 2026

Saturday, 27 June 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

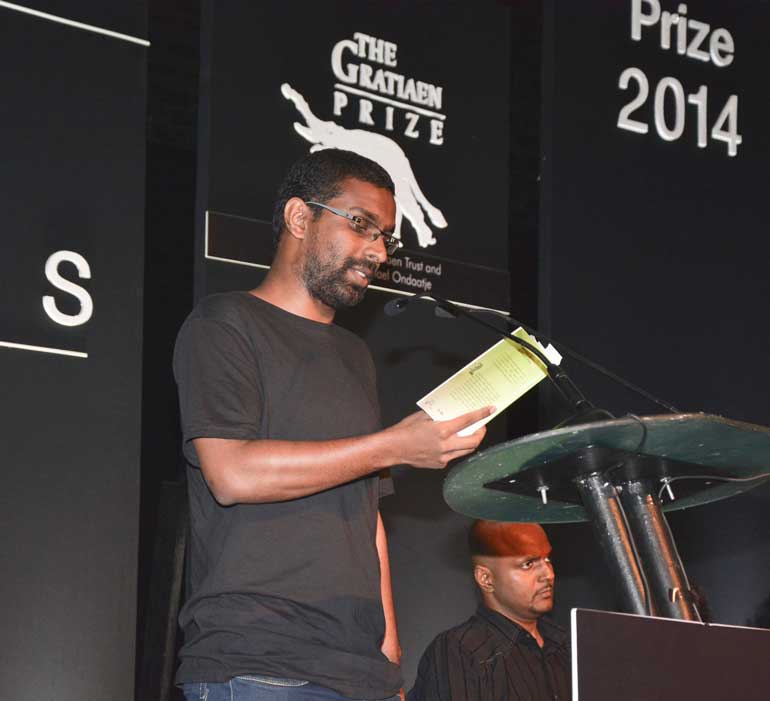

2014 Gratiaen Prize winner Vihanga Perera

By David Stephens

In much the same way that he expertly guides his words through intricate passageways of coruscating poetry and prose in his writing, Vihanga Perera does not soften them when delivering his views. His opinions, whether literary, political or social, are entirely unadulterated and frequently at odds with mainstream thought.

This unorthodox spotlight which he throws upon all the issues he examines has lent his body of work unique perspective and profound meaning. It also played a central role in acquiring him the 2014 Gratiaen Prize recently.

Portrait of composure

When I meet him to discuss his recent victory, Perera is a veritable portrait of composure, despite being framed within the midday chaos of unrelenting traffic, bustling commuters and oppressive heat.

“The feeling is good but nothing out of the ordinary,” he says about his Gratiaen Prize win. “Maybe that’s because I’m still digesting the news. It certainly puts a lot of pressure on me because the Gratiaen judges have raised the bar for the standards that I will have to meet with my future work.”

This added weight of expectation has not stymied his prolific work rate though. Presently, Perera has two projects lined up for publication, one a fictionalised memoir and the other a collection of poetry.

“My Gratiaen Prize win will give me further mileage. Moving forward, I see things being very positive for me as this victory gives me recognition and a push of sorts,” Perera asserts.

He also says that his newly-earned accolade will force him to expend more thought, time and energy over his craft. Not that he has been previously frugal with these intangible commodities, for his easygoing demeanour belies an intense passion for the written word and a greater commitment towards its creative expression.

Unconventional poetic style

Nevertheless, he admits to earning the ire of several critics over the past 10 years which the 31-year-old has been a notable presence in the local literary arena. Perera says that much of this vitriol has targeted his unconventional poetic style, something he has refused to compromise.

“From the day I started my work I have been attacked for different reasons. One of the main things they (critics) say is it is very difficult to access or completely comprehend my work, which I don’t necessarily agree with,” he states.

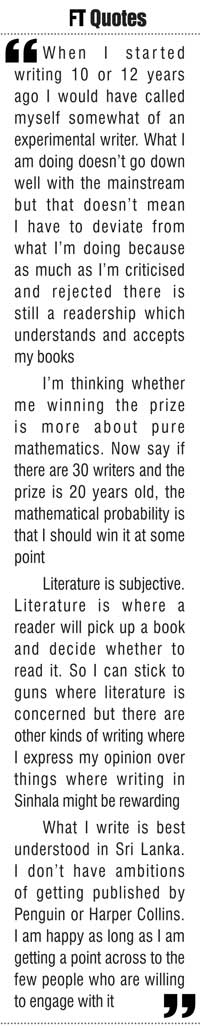

“When I started writing 10 or 12 years ago I would have called myself somewhat of an experimental writer. What I am doing doesn’t go down well with the mainstream but that doesn’t mean I have to deviate from what I’m doing because as much as I’m criticised and rejected there is still a readership which understands and accepts my books.”

He urges readers to revisit his previous work as he believes that a fair quantity of his best work has not been supplied with any kind of critical platform.

Changes in creations

When quizzed about whether his previous two unsuccessful stints on the Gratiaen shortlist in 2006 and 2008 helped alter the quality and direction of his writing, Perera replies that perhaps subconsciously he has. However, he attributes his most noticeable changes to the natural progression and maturity any writer is given to over such an extended period.

These changes in his creations have not manifested themselves as drastic recalibrations of his approach but rather infinitesimal and subtle alterations of his themes. “You find a way of balancing things, adjusting your delivery to reach the reader,” he expounds.

Matter of mathematics?

He added that the lens through which he viewed the prize had also shifted its focus and no longer perceived it as an event for a small, select crowd. He now appreciates it as a forum given to literature.

This statement acts as a fulcrum upon which the discussion pivots from Perera to the Gratiaen Prize and the country’s English literary community.

“I’m thinking whether me winning the prize is more about pure mathematics. Now say if there are 30 writers and the prize is 20 years old, the mathematical probability is that I should win it at some point,” he speculates, before his erudite expression breaks into a ripple of laughter.

“For social and historical reasons, English is very exclusive. Most people here don’t use English habitually. Sri Lanka also does not have a proper English publishing industry. So without an English publishing industry, the feeding of literature into the literary discourse as a whole is very infantile. There is no industry that brings into an amalgam the writer, reader and critic and I don’t see that changing,” Perera states.

“We are like small fish in a small pond and we have our egos. Everyone thinks they are a writer, I think that way and others do too. So for us the Gratiaen Prize satisfies our ego because in a small and narrow industry it gives us the platform that we seek. I’m sure that for 99.95% of the population the Gratiaen Prize doesn’t matter. There are other things happening; people don’t have enough to eat.”

Sinhala writing scene

Perera reveals that in contrast the Sinhala writing scene bears a more vibrant vista. He identifies the skill of these Sinhala writers to entwine their work with society’s deeper social fabric as the principal source of this rich landscape.

With English writers, he expresses that the alternate is true and their cultural experience is extremely narrow because writing books in English is an activity here most often relegated to a bourgeois indulgence.

“Writers’ access to alternative ground realities is limited. This is not true of all of them but the majority. Occasionally there might be writers who come and challenge this but I think this is how things will be by and large,” he says.

Owing to this fact, Perera is considering tapping into the wide reach of the Sinhala written word, more as a means of conveying political and social commentary than as a medium of literary expression. “Literature is subjective. Literature is where a reader will pick up a book and decide whether to read it. So I can stick to guns where literature is concerned but there are other kinds of writing where I express my opinion over things where writing in Sinhala might be rewarding.”

‘Love and Protest’

Reverting back to his work, Perera reveals that, ironically, the publication which won him the Gratiaen Prize, a poetry collection entitled ‘Love and Protest’, was compiled not by him but Paw Print Publishing.

“They approached me and told me that they wanted to publish a collection of my poetry and asked me to give them an opportunity to do so on their own. I had published three volumes of poetry before, predominantly on political themes but Paw Print said they would do a collection of love poetry. I said love poetry is very personal, I write it for my own purposes and they said you keep out of it and until the first draft came about I had no idea what they would publish,” Perera explains.

“So when they gave me the first draft I gave them the okay. They put in a few poems which dealt with politics as well and I think they should really be praised for the selection and also the editorial process.”

When asked whether he nurtures ambitions of building on his local success and making it big abroad, Perera turns circumspect. For him the appeal of writing never hinged on commercial success.

“What I write is best understood in Sri Lanka. I don’t have ambitions of getting published by Penguin or HarperCollins. I am happy as long as I am getting a point across to the few people who are willing to engage with it.”

Love and Protest is widely available at all major local bookshops.

Pix by Upul Abayasekara