Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Saturday, 24 September 2016 00:03 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By D.C. Ranatunga

It was heartening to hear that Sri Lanka’s traditional folk dances are to get a boost thanks to support from the US Embassy. A grant given to the University of Peradeniya will help in documenting and preserving four major traditional ritual dance forms and related  crafts.

crafts.

It is significant that the selections have been made from four main parts of the island.

Taking pride of place in the program is the Kohomba Kankariya – the most spectacular and complex form of Kandyan folk dance comprising an elaborate series of ceremonial dances and rituals. The origin of this dance form is traced back to the time of King Panduvasadeva (466-414 BC) who suffered from an incurable illness.

According to legend, the only person who could cure the king was King Male of Malabar. He was brought down and an extravagant ceremony was held at the Mahamevuna Uyana in Anuradhapura, the capital of the kingdom. It is said that 65 sheds were built, ornate archways and other decorations were erected and the lengthy ritual was conducted. At the end of it the king was completely cured. Thereafter it became a regular feature performed to cure illnesses and other problems and to bless the people.

“In a land of ceremonials and rituals, ‘Kohomba Kankariya’ is manifestly the most exacting of the four cults of the island,” says the Indian researcher M.D. Raghavan, who describes the process vividly in his book, ‘Sinala Natum’.

The ceremony starts with the planting of ‘kap’, the ceremonial post, three months ahead. The preparation of costumes of the dancers and other necessary paraphernalia takes quite some time.

Researcher Raghavan, who had closely watched and studied the rituals, describes the initial preparations: “The master of ceremonies, the ‘Gambara Yakdessa’, invites the ‘Mul Yakdessa’ and a band of 12 ‘Yakdessas’. The latter are detailed, six to work outside and six within the ‘Maduwa’ (shed). Those within prepare the altars (Yahana) both big and small (the Aila), collect and store the coconut oil, make torches of cloth rags (Pandam) and pound the paddy. Those who work outside go and fetch the articles needed. The supply party proceed in their collection mission (Pol Bulathyama), dressed in white and wearing Muskhavadama (the mouth gag, bringing the vegetables, yams and plantains – Keselkan Kapima).”

After the initial preparations, the stage is set for a long series of dances and ceremonials throughout the night. These begin with the invocatory dance, the ‘Yak-amuna’, by the full troupe of dancers. The Devas are invoked in dances of the most potent and vigorous character to the resounding drumming by the array of drummers. The numerous dances continue with the talented performers doing their best while being watched by the crowds who gather to participate in the elaborate presentation.

Raghavan devotes several pages in the book to describe the different dances using their correct terminology and the type of acts performed. The information will prove invaluable for the intended programs of preservation of material.

From North and East

A once popular folk dance from the North and East called the ‘Koothu’ is one of the four forms selected for the program. Also known as ‘Naatu Koothu’, this dance form exists in numerous forms depending on the regional practices which differ from one area to the next.

The word Koothu in Tamil generally means folk dance.

Of numerous forms of Koothu, at least two are the principal types. One is called ‘Vadamodi’ and the other ‘Thenmodi’. The differences in the two are in the rhythms, dances, songs and dialogue. Gradually some of these forms are being adapted to suit modern tastes and audiences. Traditionally the different ‘Koothu’ forms were created by ‘annaviyars’ – males who scripted and practised the dance forms. At least 10-12 forms of ‘Koothu’ have been created by them at the time it was a very popular form.

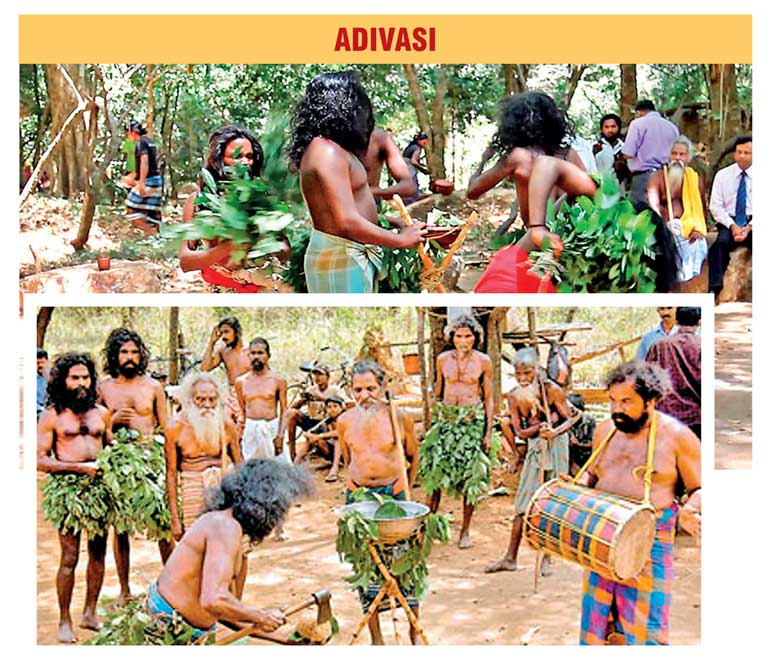

Adivasi dance forms

The traditional dances performed by the Veddas are limited. These revolve round the cult of the deceased in keeping with their beliefs and their way of primitive tribal life.

These dances are vividly described by Dr. R.L. Spittel, the authority on Vedda life. He writes in Vanished Trails: “The morning of the seventh day found all the Veddas, men, women and children, gathered at their dancing place by the foot of the hill – merely a flat clearing of the jungle that also served as their bartering ground. ‘Wadipola’ they called it. This was their sylvan temple amidst the towering trees. It contained no emblem of God, no altar. Here they were to enact a ritual as old as the rocks around them – the dance to the ‘Nae Yakku’.

“Neela, chieftain, priest and dancer all in one, stepped into the middle of the space, stabbed an arrow into the ground and set beside it a gourd of water and some boiled yams on a tripod of sticks. Holding an arrow in both hands he moved round the offering and began the ancient incantation: ‘My departed one, my departed one, my God – Where art thou wandering?’

“The monotonous chant, inviting the spirits to the feast went on and on. Almost imperceptibly the Kapurala’s walk became a shuffle, his paces lengthened. With each step he patted the ground twice with the ball of the advanced foot and his body swayed rhythmically from the waist in a half turn. His movements gained momentum as his excitement increased. Each half turn of the body was accompanied by a lowering of the head, the dishevelled hair falling over the face; and at each half turn backward, the head was tossed up.

“Some of the men joined in with snatches of song and dance, marking the rhythm by tapping their chest or abdomens, while the onlookers clapped their hands in union.”

The dance continued till Neela got into a trance believing that the Yakka had entered him. He moaned and screamed and collapsed into the hands of a person who closely followed him. He recovered after a while.”

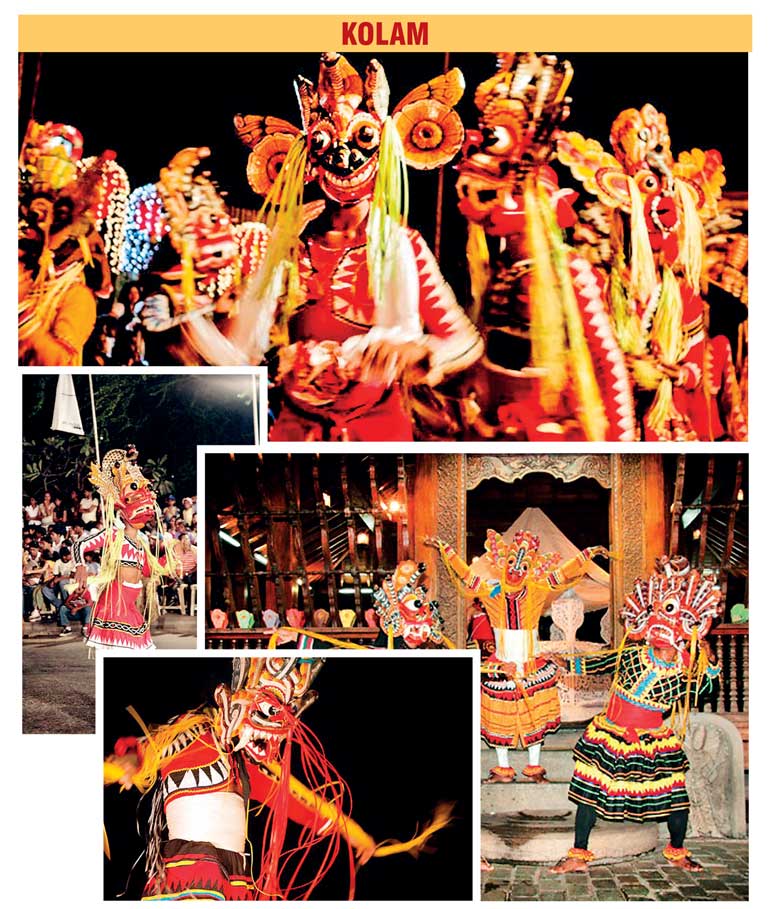

Kolam tradition in the South

The fourth item selected for preservation is ‘Kolam’, the popular folk dance prevalent in Ambalangoda. The use of masks to distinguish different characters is the distinct feature of Kolam. Raghavan explains: “There is perhaps nothing more hilarious and joyous in the whole range of Sinhala folk arts than the Kolam.”

It is generally accepted that Kolam as a masked dance-play was traditionally performed as part of the pregnancy rites. The origin has been ascribed to ‘Doladuka’ – craving of a pregnant queen who longed to see a masked dance. The king named Mahasammata is a mythical entity, who commands his countrymen to provide masks or masked dancers which they find impossible to supply. When the king was desperate, a miracle happens when masks of different forms suddenly appeared as a gift of God Sakra. Masked dances followed and the queen was pleased.

Kolam is performed as an open-air show with the audience sitting round leaving a large arena for the players. It starts with the Pothe Gurunnanse, who narrates what’s to follow. The Anabera Kolama then appears representing the king’s crier, who beats a drum and gets the attention of the people to whom he delivers messages from the king. Thereafter different characters appear. Each plays his individual part and exits. The audience is treated to an evening of light entertainment.

Drums play a key role in the range of musical instruments used in the local dances. In addition, costumes, head gear and other forms of decorative material form part of the dress. All these will also be preserved under the US aid program.