Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Saturday, 30 January 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Shiran Illanperuma

By Shiran Illanperuma

Rohini is tired of telling this story, she feels too close to it now.

The story is that of post-war Sri Lanka as told through the lives of three people. A young man abducted and tortured by the TID, his mother who campaigns for his release and a woman who joined the LTTE as a child and deserted towards the end of the war to look after her family.

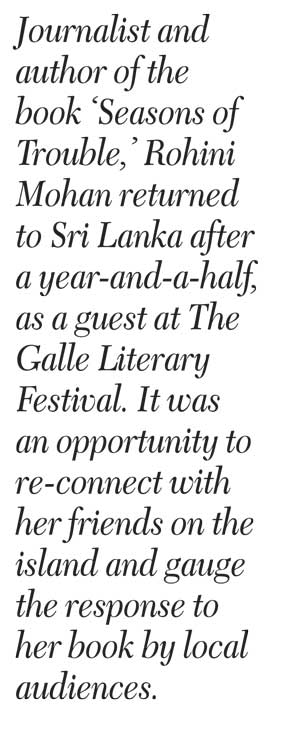

Rohini Mohan’s book ‘Seasons of Trouble’ is one of a growing cannon of literature on the ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka. Yet her approach is decidedly different. She says she deliberately chose to forego the political theory and defence jargon that often plague these stories, embracing instead a quiet humanism.

Perhaps more noteworthy is the fact that Rohini does not at any point set out to provide the definitive take on Sri Lanka’s long running ethnic conflict. Neither does she set out to write an old school journal-esque book with a subjective gaze in the vein of William McGowan’s ‘Only Man is Vile’ or more recently, Samanth Subramaniam’s ‘Divided Island’.

“The thing I thought about quite a lot was to exclude myself. A lot of publishers who rejected my manuscript said that they would accept it if I put myself in there. But somehow I had a visceral reaction to that. I didn’t want that. There was so much to say without including myself,” she recalls.

While ‘Seasons of Trouble’ in no way offers a broad overview of the conflict, it cannot be critiqued on that front. After all it is very clear that that is not its mandate. Instead it digs deep into the psyche of its subjects, whose agency and subjectivity Rohini has managed to replicate with the finesse of a fiction writer.

“It’s only through specific stories of a few people that I felt I could get to the depth of the issue. Therefore I wanted to understand greater truths through very specific details of experiences,” says the Bangalore-based journalist.

Over the five years where she reported from Sri Lanka, Rohini’s network here grew considerably. Her Acknowledgements boasts a list of contacts that would be the envy of even seasoned local journalists. Yet these relationships seem to have developed beyond their original purpose, and now anchor her to the island. Her contacts have become confidants. Too close to write about.

“I speak to them quite often. They are the reason I know this place and the reason I’m attached to this place,” she muses.

Judging by her quiet confidence when winding through Jaffna’s bustling markets and the joviality with which she hails the thambi at the local saivar kade, it’s easy to see that she’s made herself at home.

She was never this conspicuous when reporting though. Back then, during the previous regime and at the height of media repression she had to watch her back.

To blend in with the locals, she’d be sure to dress simply and leave her sunglasses at home. To avoid detection by the authorities she’d make sure to come to Sri Lanka on a visit visa, trying as hard as possible not to reveal her profession.

To blend in with the locals, she’d be sure to dress simply and leave her sunglasses at home. To avoid detection by the authorities she’d make sure to come to Sri Lanka on a visit visa, trying as hard as possible not to reveal her profession.

Every time she passed the Omanthai checkpoint, she held her breath, convinced she would be turned back.

During those days the people she interviewed, particularly in the north, would ask if she was RAW – an Indian spy. It’s a hilarious notion, but her face is deadpan serious. Trust was in short supply and it was her job to win it.

Being a Tamil-speaking Indian, she found herself uniquely positioned to report on these issues. Foreign enough to have an outsider’s curiosity and perspective but local enough to speak to local communities in their language.

However this too would have its quirks.

She says, “It was a constant negotiation about whether I was an insider or an outsider. Because I could speak some amount of Tamil I was constantly expected to also subscribe to views on Tamil nationalism that I didn’t have.”

If the question of whether she is an insider or outsider is at doubt, the signals from Sri Lanka are perfectly clear as to how they choose to position her and her writing.

Rohini’s one session at the Galle Literary Festival, a talk with fellow journalist Samanth Subramaniam, was titled ‘Sri Lanka’s War and Peace through Indian Eyes’ – emphasising her Indian-ness and her subjectivity.

Later, during the Jaffna leg of the festival, her session ended on an accusatory note when a student from Ruhunu University demanded to know why her book did not include the perspective of the south and the troubles experienced there.

Rohini says she is accustomed to these conundrums, and has grappled with them internally herself. “Why did she – a foreigner, and an Indian at that – choose to write about us – a beleaguered island nation?” is a common refrain.

It’s not an easy question. In fact, it’s quite unfair. After all why does any writer choose to write on what they do?

But to her credit, Rohini considers it carefully. Perhaps it’s a practiced consideration – one borne out of the necessity to pacify the manic questioner.

She says, “I came to Sri Lanka because the conflict here was actually resolved. Unlike the parallel situations back home, the civil war ended. So I was interested to know what it would be like to live in a place that says the war is over, but a lot of the conflict and differences remain.”

The ‘parallel situations’ referred to by Rohini include a plethora of political conflicts that have riddled the fabric of the Indian union. Though perhaps not as internationally notorious as the Sri Lankan civil war, issues like the Maoist insurgency in Central India, the separatist movements in the East and the festering issue of Jammu and Kashmir all bear similarities to Sri Lanka’s national question.

“I felt like I would learn something about the conflicts back home and the violence and what it does to people if I came to Sri Lanka. And a lot of the things I heard were very specific to Sri Lanka but they could also apply anywhere,” she remarks.

Indeed, the minute the Sri Lankan State claimed victory over the LTTE, her neighbour paid heed. Indian leaders began touting the so-called “Sri Lankan solution”, for all of the nation’s conflicts. A solution, which Rohini jokes, is to “bomb everything”.

As a writer and a journalist, Rohini seems quite done with Sri Lanka. She’ll still report on it to be sure, but she’s eager to move on. Her eyes glaze over when questioned about the possibility of writing a sequel to her book, but they light up when she speaks of pursuing other stories in other lands.

One wonders how she will write on conflicts elsewhere in the world, now that she’s had a glimpse of how they might end.