Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Saturday, 23 January 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Shiran Illanperuma

VisakesaChandrasekaram used to walk down the trendy streets of his Sydney suburb, fingers intertwined with his partner’s. Once, he came across a flower that reminded him of home. But upon closer inspection he found that it was, like him, different.

VisakesaChandrasekaram used to walk down the trendy streets of his Sydney suburb, fingers intertwined with his partner’s. Once, he came across a flower that reminded him of home. But upon closer inspection he found that it was, like him, different.

Visakesa says, “I was thinking how best to explain this to a general audience and thought that a frangipani would be a good metaphor. This flower very rarely comes with six petals, instead of five. You might see it if you look for it but otherwise you might not see it at all. It’s natural.”

Visakesa’s debut film ‘Frangipani’ has screened at a number of LGBT film festivals throughout the world, from the Bangalore Queer Film Festival to the Hong Kong Lesbian and Gay Film Festival to the Mardi Gras Film Festival in Sydney. Yet throughout the 90 minutes of the Sinhala drama, the words ‘lesbian’, ‘gay’, ‘bisexual’, ‘transgender’ or ‘queer’ are never uttered.

This is deliberate, says Visakesa. “Issues of sexuality and labelling are not very common in the Sinhalese language. The whole acronym of ‘LGBT’ comes from the Western community. When you try to translate these things and take the message to ordinary people, it becomes very complex,” explains the lawyer-turned-author-and-playwright.

This is deliberate, says Visakesa. “Issues of sexuality and labelling are not very common in the Sinhalese language. The whole acronym of ‘LGBT’ comes from the Western community. When you try to translate these things and take the message to ordinary people, it becomes very complex,” explains the lawyer-turned-author-and-playwright.

Indeed it is precisely for these reasons that the LGBT community in Sri Lanka has intermittently come under fire from conservative gatekeepers who charge that sexual practices and identities that deviate from heterosexuality are against Sri Lankan culture.

While organisations like Equal Ground, Sri Lanka’s only high profile advocacy and support group for the LGBT community, wage their activism on a legal basis through a human rights framework, artists like Visakesa choose to hit back on the cultural front.

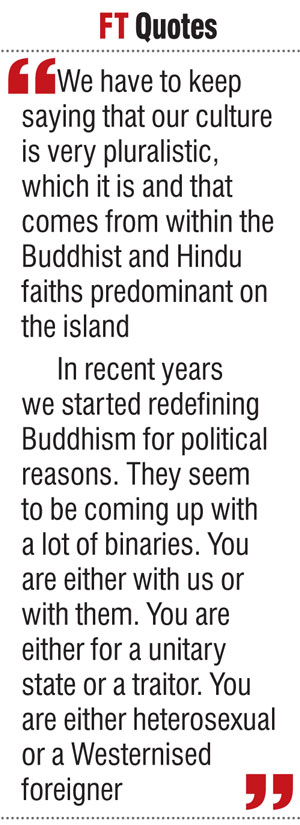

For Visakesa, the fight for LGBT rights is also a fight to reclaim culture from the stubborn hands of nationalists. “We have to keep saying that our culture is very pluralistic, which it is and that comes from within the Buddhist and Hindu faiths predominant on the island.”

As a lawyer himself, Visakesa is no stranger to human rights discourse, having represented political prisoners and researched controversial issues such as Sri Lanka’s counter-terrorism laws. However, despite his legal qualifications he is convinced of the need to wage political struggle as an artist.

“Artists have a strong voice and some sort of power. We need to have a deconstruction of culture and reclaim space for minorities,” he appeals. “I use art to encroach into these spaces.”

Visakesa who has previously created art as a playwright and author, chose to tell the story of Frangipani through cinema for the mass appeal of the medium. Indeed, the trappings of the film itself are quite familiar. A rural setting, a young male protagonist with ambitions of economic success and a budding romance with an eligible village girl. This could be any number of Sinhala tele-dramas or the Bollywood hits that inspire them.

“I was conscious that we were going to talk about a somewhat unfamiliar topic to the Sri Lankan audience. I purposely adopted the film narrative styles familiar to local peoples with music, dance and the emotional presentation of close-ups. I wanted to do that rather than going for a very highly technical or art house structure, which may not be user friendly,” he explains.

As accessible as the generic conventions in Frangipani are, Visakesa doesn’t shy away from tackling the film’s themes head on as the narrative unspools. Subtle as it is, Visakesa offers a biting critique of masculinity and Sinhala Buddhist nationalism, particular in the way these ideologies affect gay men.

Visakesa’s main protagonist in Frangipani is Chamath, a young man coming to terms with his sexuality.

The younger of three brothers, he occupies a nebulous space of potential and expectation. One of his brothers is a sagely Buddhist monk, the other, a square-jawed soldier or police officer.

A boy caught between a monk and a soldier, the two ideals of Sinhala masculinity.

“The reason I positioned this character between those two was to symbolically assert his existence. He has a right to be there between them,” charges Visakesa. ‘He’ of course, is an avatar for any gay man in Sri Lanka, including Visakesa himself.

The monk and the soldier are figures who have dominated Sri Lanka’s post-independence cultural milieu, sometime even overlapping in strange and surprising ways. While these transformations have often been identified in the context of the ethnic conflict and the national question, Visakesa hones in on their effects on sexual minorities.

“In recent years we started redefining Buddhism for political reasons. They seem to be coming up with a lot of binaries. You are either with us or with them. You are either for a unitary state or a traitor. You are either heterosexual or a Westernised foreigner.”

But queerness, Visakesa is adamant, is not a Western import. In fact as he points outs it is Section 365 and 365A – the ominous sword over the head of the LGBT community that outlaws their identity and lifestyle – that is the Western import as an artefact of British colonial rule.

Speaking on the character of Chamath, Visakesa says: “If people say he is Westernised because he is gay, I say no he is not. He grew up in a village, he had his first attraction to another man in a village temple. How can you think that is Western?”

Back home in Colombo, Visakesa still likes to take walks. His fingers seek that of his partner’s almost instinctively as they stroll along. He draws them back for a moment, considering the risk, then realises: In Sri Lanka, unlike the West, it’s completely normal for two men to hold hands.