Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Saturday, 11 March 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

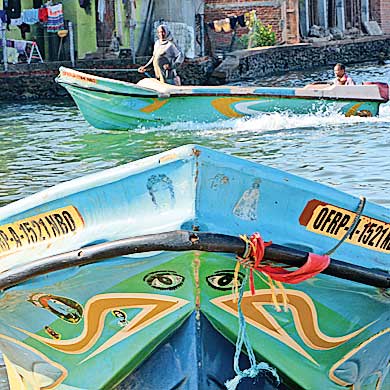

Daily FT Photojournalist Shehan Gunasekara visits the Negombo ‘Lellama’ and tells the story of a resilient people who work very hard to make just enough to live

At 3:30 a.m., when not just the neighbourhood but most of the country is shrouded in sleep, the Negombo Pitipana ‘Maha Lellama’ (fish market) is already a hive of activity. From the Mankuliya Bridge onwards right up to the Lellama, one sees wave after wave of people in vehicles and on foot making their way to purchase fresh fish straight from the sea.

Amidst the hustle and bustle at this early hour, I joined the crowd and made my way to the Lellama among the throngs of people.

What unfolds here each day is an auction of the catch by boats, especially multi-day fishing boats, and a day’s trade is in the range of Rs. 1.5 million.

It’s a vibrant and noisy place, full of action, and it’s so crowded here that people are constantly pushed about by fishermen and vendors carrying around massive hauls of fish.

I saw the boats that had gone out to sea parked at the jetty. Some had been at sea for two weeks, some for even longer. Weather permitting, 10 to 15 boats come here each day with their catch.

I then watched in awe as a huge heap of tuna was piled up in one corner, and in another saw a big catch of shark being unloaded.

The Manager of the lellama, Anton Lakmal, had this to say about the shark haul: “It is not brought by the boats, the sharks are from freezers in the south. They can’t get a good price there so they come here and sell the fish for karavala, which isn’t usually made in the south. That’s why they sell it here for karavala. Sometimes there are sharks in the boat hauls as well but not in wholesale quantities like from the south. It does not happen every day, perhaps once a week.”

After watching the ongoing activity at the lellama for a while more, once the sun was up I headed towards the Kuttiduwa Fish Market.

“Sir, are you Sinhalese?” a girl drying karavala in the burning hot sun asked me, as I tried to take some pictures. When I replied in the affirmative, she said, “Then please don’t take pictures!”

I complied with her request silently, realising she may have said this because she did not want anyone she knew to see the pictures in a local paper, which she probably felt would result in shame or disrespect from society.

I didn’t tell her that there was no difference or division in jobs in terms of being high or low and that every person was doing some form of service.

Everyone at this fish market is involved in the fishing industry in some way. About 4,000 boats go to sea from here every single day. Some leave at 2 a.m. and return by 8:30 a.m., others go out all night and return early in the morning. They sell as much of the catch as they can to vendors and turn the remainder into karavala.

A fisherman who was cutting up fish for karavala explained the process: “We cut up the fish and add salt, then pack it in barrels for two days. Then it is washed in water and dried in the hot sun.”

Even though he makes it seem so easy, the actual process is extremely arduous. They work in the burning hot sun with towels covering their heads, with no rest and few returns. The little money they make goes towards feeding and educating their children. “It is enough to live,” they tell me, “but not enough to do anything more.”