Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Saturday, 25 July 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By D.C. Ranatunga

The festival season is on. As it happens every year, the Kataragama festival gives the lead.

Today Kataragama can be reached within a matter of a few hours from any part of the country. The road network is so streamlined. From a sleepy village, Kataragama has woken up to be a modern town. But not many may know that it was a difficult and hazardous journey in the years gone by.

‘Denagiya giyoth Kataragama – Nodena giyoth Ataramaga’ (if you know the way you will get to Kataragama – Otherwise you will find yourself stranded) was a common saying. It was a warning that anyone going to Kataragama should be well-versed on how to get there.

It was such a risky trip since most of the way was jungle land. The pilgrims were warned to be extremely careful in what they uttered and how they behaved themselves. Because they were going into the ‘deiyange rata’ – the god’s territory.

Journey to Kataragama

The journey to Kataragama in the early part of the 20th century is best described by Sir Leonard Woolf, the young Englishman who came here as a cadet of the Ceylon Civil Service, the small group of white administrators who ruled the island.

The 28-year-old lad was soon made the Assistant Government Agent – the chief administrator and judicial officer – at Hambantota at the far end of the Southern Province. Most of the sparsely-populated area was malarian jungle in the dry zone of South Ceylon, as the country was then known. Woolf traversed the length and breadth of the district either by walking, or riding his pony and the bicycle.

The Kataragama festival has a long history. Administrator turned writer Leonard Woolf, best known for his book, ‘The Village in the Jungle’, describes the festival during his time around 1910.

“I rode to Kataragama from Tissa (Tissamaharama) on 8 July and I stayed there for 14 days, when the pilgrimage ended. There were between 3,000 and 4,000 pilgrims. Many of them were town dwellers who had never seen a jungle. They had travelled by sea and train to and through a strange land; men, women and children who had trudged 180-200 miles along the roads and on the jungle track to find themselves dumped for a fortnight with three or four thousand other people in a clearing in a dense jungle. For Kataragama in 1910 was a little more than a large clearing in the unending jungle. It had two temples, one at one end of what might euphemistically be called the village street – it was only a very broad path between boutiques and sheds – and the other at the other end.

“Every evening the image of the god was carried in procession to the other temple – a kind of juggernaut procession with the pilgrims following or rolling over and over the dust before the god’s car. In the other temple was his wife and after visiting her he returned to his own temple. On the last day of the festival priest and all the pilgrims went to the river with the image of the god and there, standing in the middle of the river, the priest ‘cut the water’ with a knife – and the festival was over.”

Fifty years later, in 1960 when Woolf was here on a short visit. He was keen to go and see the area he served. He describes what he saw thus: “The jungle track from Tissa had been converted into a food road over which I was comfortably driven in a car. My recommendation has certainly been carried out, but the Kataragama of 1910 that I knew had disappeared.”

Today roads in and around Kataragama are excellent.

Common to Buddhists and Hindus

From the early days Kataragama has been a place of worship for Buddhists and Hindus alike. Historian, Dr. Kingsley de Silva states that along with the veneration of Mahayanist deities the worship of vedic and post-vedic Hindu deities was firmly established as part of religious practice of Sri Lanka Buddhism. That is how shrines have been built in the name of gods in the predominantly Buddhist areas.

The ‘devale’ at Devinuvara dating back to the 7th century CE and another at Alutnuvara in the Four Korales – both in the name of Upulvan – are two examples. The shrine at Kataragama is dedicated to Skanda. Upulavan, Saman, Vibhishana and Skhanda are accepted as the guardian deities of Sri Lanka. Devales are a common feature in most Buddhist temples.

Kataragama is also one of the 16 places visited by the Buddha and the erection of Kiri Vehera commemorates the event. Most Buddhist, as a rule, first worship Kiri Vehera before proceeding to the Kataragama devale. Many observe ‘sil’ at Kiri Vehera. While there are Buddhists who make vows mainly for illnesses, praying for God Kataragama’s help to get cured, there are others who make a routine trip to Kataragama once a year with the belief that they will have a trouble-free year . Most businessmen do the trip without fail to pray for a better year for their business.

Devotion, the key word

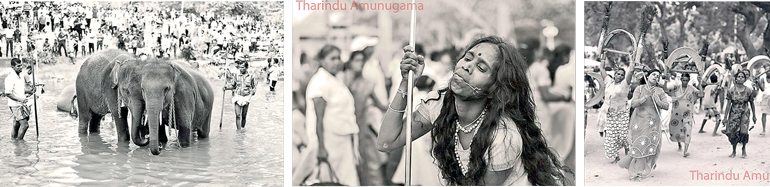

Devotion is the key word at Kataragama. The festival season see a lot of Hindu devotees doing penance in the compound in front of the main devale. Some drag themselves from one end to the other. There are others with skewered cheeks or dragging something heavy with hooks tied to pierced skins.

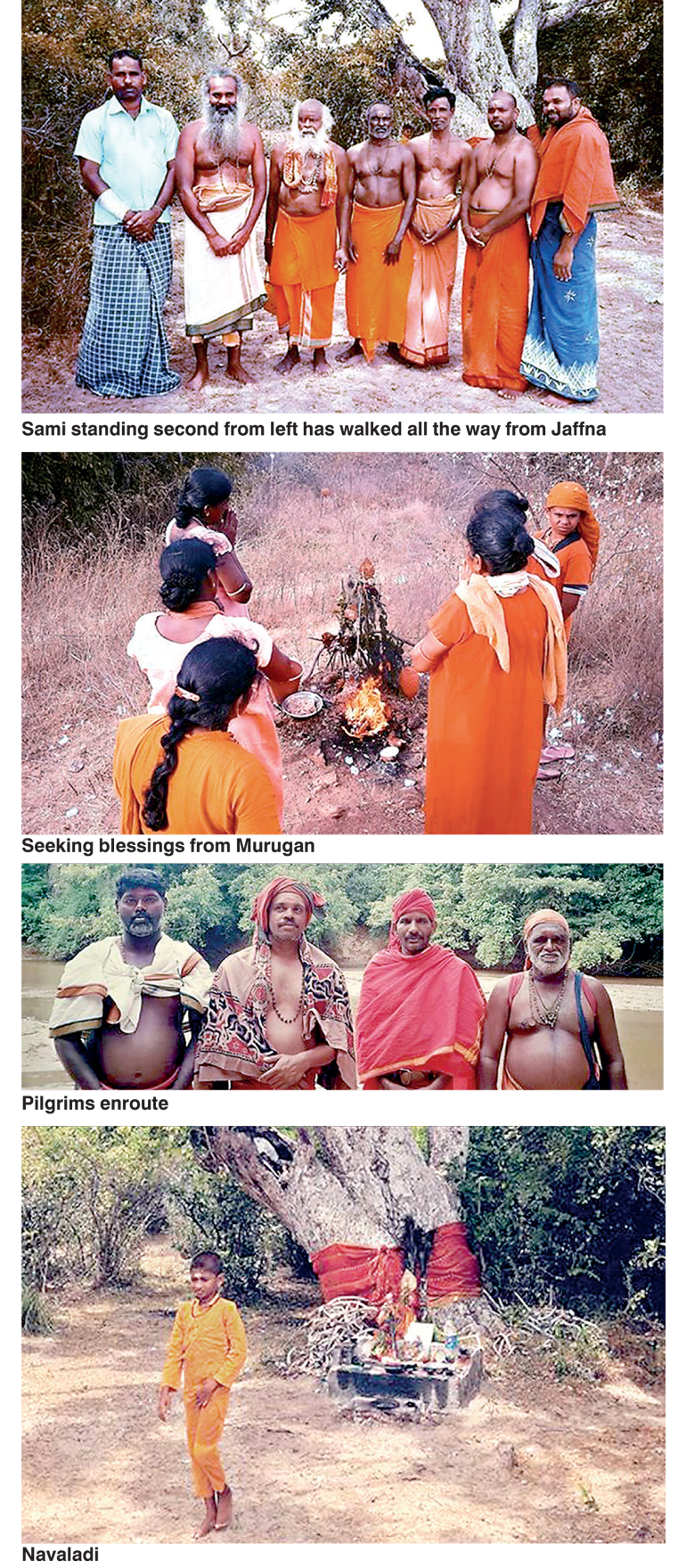

‘Kavadi’ is yet another popular feature where pilgrims carry peacock-plumed frames on their shoulders. Drummers accompany ‘kavadi’ dancers who are seen in groups coming from long distances walking all the way. Then there is ‘pada yatra’ where hundreds of pilgrims walk from up-north and from the east coast starting the trudge months ahead of the festival.

Fire-walking on the final night of the festival still draws large crowds. They watch devotees walk over a mass of embers raised by burning logs. Those who walk across claim that their faith prevents them from any harm caused by stepping on the hot embers.

Pix by Tharindu Amunugama