Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Saturday, 25 June 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

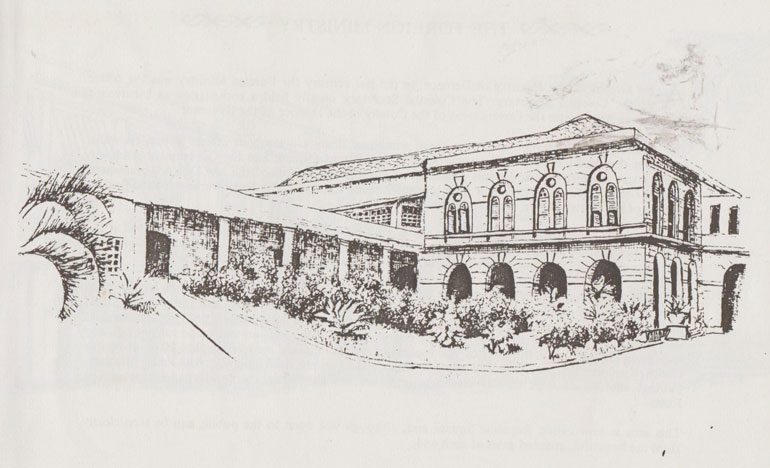

Pic courtesy: 'Colombo Heritage'

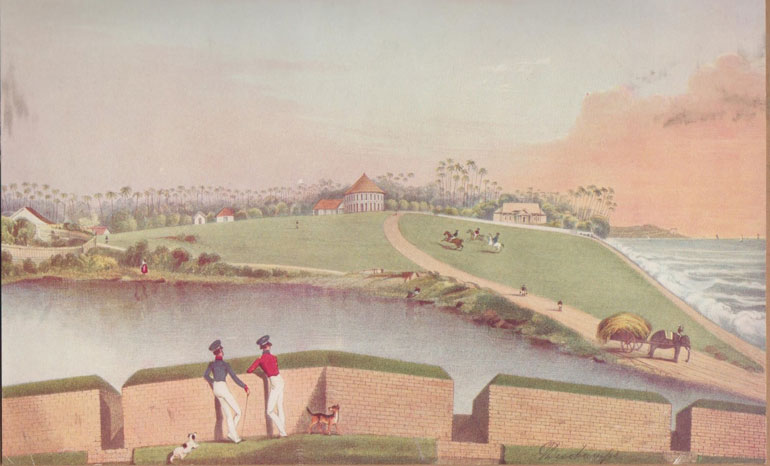

Galle Face then – Painting by Capt. Deschamps

An estimated 300,000 men, women and school children had gone to see the ‘Raja Gedera’ earlier this month when President’s House was opened for public viewing for six days. Being the official residence of the Head of State, it was never open to the public since the days of the British Governors dating back to early 1800s.

Originally built in the 18th century by the last Dutch Governor J.G. van Angelbeek, the House became the property of the British Government in 1804. In ‘Colombo – A Centenary Volume’ (1965), H.A.J. Hulugalle discusses the “somewhat strange circumstances” under which it passed over.

“Angelbeek’s niece, Jacomina Gertrude Van der Graaf married an English Civil Servant, the Hon. George Melville Leslie. When a shortage of over £10,000 was discovered during his 16 months’ tenure as Paymaster-General, his wife’s family rallied round and generously offered to hand over the house to the Government at its own valuation of 35,000 rix dollars, and this was accordingly confirmed by a deed dated 17 January 1804.”

The house was described as “the largest and best dwelling house in the Fort of Colombo… situated in the principal street and composed two regular storeys. From the upper balcony on one side is an extensive view of the sea, the road and shipping. On the other is a rich prospect, comprehending the lake, Pettah, cinnamon plantations, and a wide range of the inland territories bounded by  Adam’s Peak, and many lesser mountains.”

Adam’s Peak, and many lesser mountains.”

It was considered a fitting place for a Governor to reside. The land area was nearly six acres and was valued at Rs. 4 million.

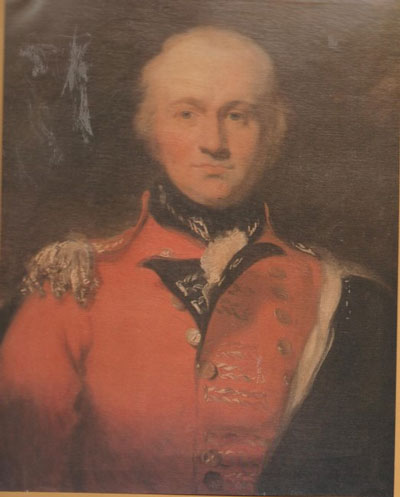

The first Governor to reside here was Sir Thomas Maitland who came in 1805 after Fredrick North (1798-1805). The first instance when the Governor’s House became a hive of activity was during the tenure of Maitland’s successor, Sir Robert Brownrigg (1812-20) in planning the invasion of the Kandyan kingdom. While earlier attempts had failed, the stage was set after King Sri Vickrama Rajasingha fell out with the Kandyan chieftains who started manoeuvring with the British.

Following the beheading of the first adigar Pilima Talavve when a plot to assassinate the King failed, Ehelepola, Pilima Talavve’s nephew, succeeded him but the King was suspicious of him too. He ultimately fled to Colombo seeking protection from the Governor. The British found a valid excuse to declare war when 10 Moor traders from Mahara who were trading in Kandy were accused of being British spies and were mutilated, the nose, the right ear and the right arm of each being cut off were sent back.

Brownrigg regarded this “wanton, arbitrary and barbarous peace of cruelty” inflicted on British subjects as sufficient justification for war. Taking personal responsibility, he declared war on 10 January 1815. Kandy was occupied on 14 February and the King was taken into custody four days later at Gallehewatta in Dumbara. That marked the end of Sri Lanka’s independence.

Festive mood

The Governor’s House got a reputation for great festivities during the time of Edward Barnes (1824-31) who got married to a wealthy female from a Yorkshire family. Considered as one of the ablest administrators the country had, Barnes is best known for his efforts at building roads and bridges. Following his first tour of the island he had concluded that what Ceylon needed was “first roads, second roads and third roads”.

He promoted the growing of coffee which became the first plantation crop, built Governor’s residences in Nuwara Eliya and Kandy, opened rest-houses at Ambepussa and Ragama, introduced a license system for the sale of arrack, promoted local industries and increased exports. A bronze statue stands as a symbol of gratitude at the ‘out gate’ of President’s House at the beginning of the  road from Colombo to Kandy which was built during his administration. Mileage to places from Colombo is measured from this point.

road from Colombo to Kandy which was built during his administration. Mileage to places from Colombo is measured from this point.

The governor’s residence was named ‘Queen’s House’ with the accession of Queen Victoria to the throne in June 1837. It was the final year of the administration of Governor Sir Wilmot Horton (1831-37). Extensive repairs had been done during the last two years of his regime when “the greatest part of King’s House was taken down and rebuilt”. Again in 1852, it had been “practically rebuilt by Durand Kershaw, Assistant Civil Engineer, at a cost of £ 7,000”, according to the ‘History of the Public Works Department (1921-3)’.

Interesting occupants

In the well-illustrated publication ‘From Governor’s Residence to President’s House’, Brendon Gunaratne states that the more interesting occupants of Queen’s House were the literary-minded Sir Henry Ward (1855-60) and Lady Ward. The Galle Face promenade – Colombo’s ‘Park’ or ‘Prater’ – was his contribution to the pleasures of life in Colombo. He established the railway line from Colombo to Kandy and a statue to commemorate him was erected in Kandy by public subscription.

A passage from one of his speeches was inscribed on its pedestal which read: “My conscience tells me that to the best of my judgement and my abilities I have tried to do my duty by you, and it is my hope that you will think of me hereafter as a man whose heart was in his work”.

Hulugalle in ‘British Governors of Ceylon’ records an interesting conversation with the Editor of ‘The Examiner’: When John Bailey, the husband of one of his daughters, became Principal Assistant to the Colonial Secretary, accusations of favouritism were aired in ‘The Examiner’. Sir Henry summoned the Editor, Charles Ambrose Lorensz, a Ceylonese lawyer of distinction, to Queen’s House and said to him: ‘Lorenz, what’s all this fuss about Bailey? What’s the use of my being Governor if I cannot have my daughter to stay with me in Colombo?’ No more was heard of the charge of favouritism. The second daughter’s husband, Alexander Young Adams, who began life as a planter, became Director of Education and acted as Auditor-General.

Royal visit

The first visit by a member of the Royal family had been in 1870 by Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, second son of Queen Victoria. Governor Sir Hercules Robinson (1865-72) put on a dazzling show for the Prince and his party. The reception held at Queen’s House “proved the most brilliant and numerously attended of any that had ever been held in Ceylon. The Royal presence brought together chiefs and head men who had not left their jungle homes for half a lifetime,” it was reported.

The first visit by a member of the Royal family had been in 1870 by Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, second son of Queen Victoria. Governor Sir Hercules Robinson (1865-72) put on a dazzling show for the Prince and his party. The reception held at Queen’s House “proved the most brilliant and numerously attended of any that had ever been held in Ceylon. The Royal presence brought together chiefs and head men who had not left their jungle homes for half a lifetime,” it was reported.

Another royal visitor was Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) who came in 1875 and was the guest of Governor Sir William Gregory (1872-77.

Not many governors had left their impressions on Queen’s House. Governor Gregory writes in his autobiography that he was “surprised and elated” by its size and grandeur. “The bedrooms large and airy, each with its own bath, large enough to swim in; the drawing room seventy-five feet long, looking out on the sea and on a garden, in which were growing trees all decked out with flowers, some of them most gorgeous, such as I had never seen before – Barringtonia, with its grand leaves and showers of white flowers; the pandanus, a towering banian and innumerable others…..The house was lighted up and furnished at Government expense. Glass and crockery were also provided, on which I had to pay five per cent for the use. Besides the private servants paid by myself, there were 12 other servants in uniform, kept up by the Government, as was also the garden. The same arrangements prevailed at Kandy, and subsequently, at Queen’s College, Nuwara Eliya.”