Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Saturday, 8 September 2018 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Skandha Gunasekara

Pinocchio, the Italian folktale from our childhoods, is usually the first thing that pops to mind when puppets are spoken of; however the tradition of string puppeteering is very much a part of our culture with its very own Lankan twist.

Puppetry and string puppeteering has been part of Sri Lankan culture for centuries, with its roots in the south of the island.

String puppeteering was started in the 1850s by Puppet Master Ganwari Podisirina of Amabalangoda, who held the first public string puppet show.

As the story goes, a British knight, Sir Wales, who was visiting the island in 1922, was the first State official for whom Ganwari held a performance. Wales, who had been greatly entertained, had given Podisirina Rs. 500 and a gold biscuit soon after the show.

Generations later, Ganwari’s great grandson, Supun Chathuranga Gamini, is continuing this traditional art form and has now taken a step further by setting up Sri Lanka’s first, and only, Puppet Museum.

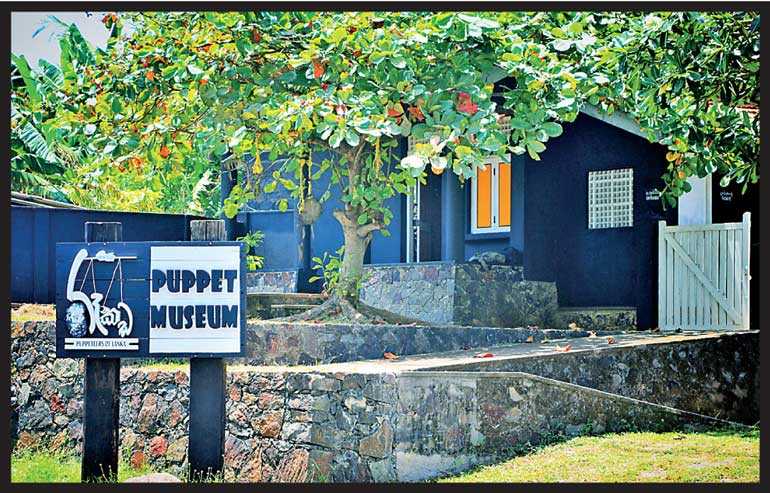

When travelling south from Colombo along the Galle road, while passing through the hamlet of Balapitiya, just before the town of Ambalangoda, lies Sri Lanka’s only traditional Puppet Museum.

The museum was established in 2017, on 21 March – World Puppet Day, by the Puppeteers of Lanka organisation. Traditional Sri Lankan puppeteering originated in the south of the island, particularly in Ambalangoda and Balapitiya.

During a visit to the museum, Gamini, elaborating on his family’s contribution to string puppeteering in Sri Lanka, recalled how his great grandfather had begun the tradition of string puppet performances.

“My great grandfather, Ganwari Podisirina, gathered together all the puppet masters from the region to form a group. These individuals had various strengths in puppeteering. Some were good at carving puppets; others were proficient in painting the intricate designs and features on the puppets, while some others were good at manipulating the strings for performances. My great grandfather wanted to take this art form to the people,”

He describes how string puppeteering helped bring back Nadagam-style dramas, which, at the time, were being overshadowed by Nurti dramas.

“My grandfather Ganwari Jemis, continuing his father’s trade, held a performance at Viharamahadevi Park to celebrate Sri Lanka’s independence. This performance was witnessed by the then Prime Minister D.S. Senanayake, who thereafter awarded a gold medallion to Ganwari Jemis in appreciation. The puppet shows were Nadagam style with music and singing; this resulted in a resurgence of this form of drama.”

Gamini, who is the founder and present curator of the Puppet Museum in Balapitiya, explains how and why he decided to set up the establishment.

“Back in 2004, my uncle, Ganwari Premin, began a puppet museum in Amabalangoda but that was destroyed that very same year by the Boxing Day tsunami. String puppeteers has become a fast-diminishing traditional art and when I was studying arts at the Peradeniya Campus I realised it was greatly underutilised; therefore I decided to set up a museum to honour and safeguard its history and ensure its future.”

Gamini reveals that there are only 10 groups in the entire country which practice and perform this traditional art form. He is the leader of one of the most prominent of such groups, the Puppeteers of Lanka.

The Museum was set up with the help of a generous benefactor who donated Rs. 1.5 million and has three main areas. The first contains some of the very first puppets made by Gamini and his family and depicts the history of puppeteering in Sri Lanka, from what type of wood and how the puppets are made to what stories and dramas were most popular during its inception.

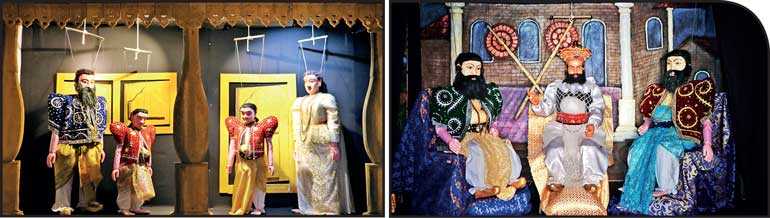

“The best wood to make puppets is from the Kaduru tree. The wood from this tree is easy to cut and mould. Pests such as weevils and termites don’t infest this wood and it doesn’t rot easily when exposed to sunlight or dampness. It takes about eight hours to cut and mould the wood into a puppet. Thereafter we have to paint it. Back in the day it was all naturally sourced inks that were used to paint the puppets but now it is much easier to use artificial colours. After its features have been painted and dried, we have to adorn it with clothing and accessories that fit its character in the play. A puppet takes about a month to complete.” The Puppeteers of Lanka performs roughly 15 different puppet dramas including historical and religious legends and sagas.

Apart from preserving the tradition of string puppeteering, Gamini also plans to modernise string puppet theatre.

“We are currently experimenting with different audiences. Foreigners particularly like our religious and historical tales while kids and students prefer more comical performances.”

Concerned about the lack of new pupils entering puppetry, Gamini hopes to draw more public attention by carrying out mobile performances across the country.

“During the Vesak and Poson season, we travel around the country, performing in schools and temples. One of the main reasons this art form is shrinking is because no new artists want to join. We hope to attract more students to string puppeteering by playing in schools and temples. We have already received great feedback from some schools.”Apart from entertainment, Gamini also wants to make puppet performances educative.

“We have started a few new storylines, on more contemporary subjects and issues. We have partnered with a television channel to create a series for children. This could be a better alternative for young kids to watch instead of cartoons.”

From the time Ganwari Podisirina began conducting string puppet shows, families in the south, like that of Supun Gamini, have diligently continued this dying tradition despite its minimal financial returns. One can only hope that Gamini and his fellow puppeteers are able to revitalise string puppeteering; and that these traditions that have such historical and cultural significance do not vanish in the face of incessant Westernisation of Sri Lankan culture.