Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Saturday, 4 August 2018 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Madushka Balasuriya

Sri Lanka’s wildlife tourism potential is not news to anyone. With large mammals, both land-based and in the oceans, observable from coast to coast, not to mention the off-coast shipwreck diving excursions – with their own selection of underwater creatures – which are slowly but surely gaining in popularity, Sri Lanka is truly a wildlife goldmine.

That this is the case for an island of its size makes it even more extraordinary, but the true extent to which Sri Lanka struck geographic gold is no more exemplified than when taking into consideration the country’s vast array of birdlife.

“We take it for granted, but people who travel here are amazed that in this small island we have this scale of things which are on a continental scale,” notes one of Sri Lanka’s most prominent wildlife personalities, Gehan de Silva Wijeyeratne.

Wijeyeratne – an author, photographer and publisher – is a minor celebrity of sorts in Sri Lankan wildlife circles, and he recently gave a presentation on the ‘Endemic Birds of Sri Lanka’ at the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society’s monthly lecture series.

“A lot of foreigners who have travelled here just can’t believe we have so much activity in such a tiny island. The geology is awesome, the landscapes are incredible, and the sheer diversity of habitats is really, really broad,” he adds.

“Very few people realise how lucky we are that Sri Lanka is as rich as it is”

When it comes to birds, Sri Lanka is home to 464 of some 10,000 documented species worldwide. While that may on the surface look like small change, in that it accounts for merely 4% of global figures, a closer look at the numbers paints a rather more impressive picture.

First it should be clarified that when documenting such a vast array of species, wildlife scientists have looked to make things easier by segregating each of them into one of 36 bird orders, of which Sri Lanka accounts for 22 – 61% of the global total. To top it off Sri Lanka is also home to 34 endemic species – birds you won’t spot anywhere else on the planet. And with most bird species in Europe having their origins in Asia, Sri Lanka’s density of bird orders makes it one of the best spots in the world to actually begin learning about birds, a fortunate turn of events that many in the country fail to realise.

“Very few people realise how lucky we are that Sri Lanka is as rich as it is, because it is an unbelievable accident of nature the way we’ve ended up so rich,” notes Wijeyeratne.

“As a tropical island you assume it’s going to be lush and beautiful. But if you look at the map and if you go West on the same latitude, you come to the hall of Africa and you see it’s very dry and barren. So just where you are – near the equator itself – doesn’t make you a lush tropical island. And there are islands off the northern coast of South America like Aruba, which are really dry and very species poor.”

Indeed, compared to other large tropical islands such as Madagascar, Borneo and New Guinea, Sri Lanka has a very high relative richness of species per unit area, explains Wijeyeratne.

“I’m not cheating. I’m not comparing Sri Lanka with Britain, or Iceland, or Greenland, or somewhere with a high latitude. Because we all know that when you’re closer to the tropics you have more species.

“Islands like Borneo at one point were entirely rainforests. So they’re very species rich. But if you look at the comparative scale, you can see how Sri Lanka is way above those other large tropical islands – which are like 10 times the size of Sri Lanka. So you would expect them to have more species per unit area. But surprisingly Sri Lanka beats them all.”

“Sri Lanka was actually made for wildlife tourism”

The reason for Sri Lanka’s “super-rich” nature when it comes to speciation, explains Wijeyeratne, is down to a combination of reasons. For one, the island’s location puts it in an ideal spot for a rain shadow cast by the Western Ghats mountain range in India. What the rain shadow does is it essentially creates a dry zone in areas like Puttalam and Chilaw, but wet zones in others.

“If Sri Lanka was another 150-200km further north, the whole country would have looked like Mannar. If it was maybe 200km further down, the whole country may have looked like Sinharaja,” he exclaims.

“We would have either had a huge amount of biodiversity and endemic birds, or we would’ve been entirely a dry zone – maybe like Yala, which supports large mammals. So you can see, Sri Lanka was actually made for wildlife tourism.”

Furthermore, Sri Lanka is also host to two diagonally blowing monsoons and a central mountain range, while there are also several river systems. Add to this geographic anomalies such as deep seas close to the shore along with shallow seas near the mainland, and a picture begins to form of a country that is really in a goldilocks zone that enables a series of wildlife spectacles; a high proportion of endemism; increased speciation; and all easily viewable.

“Although lots of other destinations may have bigger rainforests and more species, the combination, such as the big game, the endemicity, the infrastructure, when you take all of that into account very few destinations have what Sri Lanka has,” opines Wijeyeratne.

“Everything that scientists come up with continues to reinforce that Sri Lanka is actually very special”

Another aspect that might go unnoticed is the country’s geographic past, where an ancient land bridge between Sri Lanka and India might also have contributed to the country’s unique array of species.

The 50km bridge made of limestone shoals, known as Adam’s Bridge or Rama’s Bridge, is believed to have connected the south east coast of Tamil Nadu and Mannar. It was reportedly passable on foot up to the 15th century until storms deepened the channel.

“The land bridge is not really what contributed to the species diversity in terms of the endemics, but when the sea levels went down, we had this land bridge connection with India and that would’ve contributed to the dry zone wildlife we see. Things like the elephants and the leopards would certainly have been helped by the land bridge, but the endemics in Western Ghats and Sri Lanka would have been separate.

“So no one exactly knows what the physical conditions were during those last 150 million years that have influenced what we have in the country. But everything that scientists come up with continues to reinforce that Sri Lanka is actually very special. And this has obviously been translated to foreign exchange from wildlife tourism.”

“There are also few endemics you can pick up in Colombo… if you know what to look for you might even see it in the BMICH grounds”

According to Wijeyeratne, while the best place to spot endemic birds in the country is at the Sinharaja Forest, there are also sightings to be had in Colombo. This is along with several species that can also be found in the mountains as well as the dry zone.

“The best places are actually in the wet zone, because our wet zone forests both in the lowlands and the highlands have been separated from India - it’s almost as if there’s an ocean between them. Even when there was a land bridge connecting them, that dry zone land worked as a barrier.

“If it’s an endemic you’re after then you need to go to an island that has been isolated for millions and millions of years. That’s places like wet zones, where you have forest patches like Bodhinagala, which is actually not too far from Colombo and Sinharaja. Then there’s Kithulgala which is a mid-elevation forest, and it connects up with Horton Plains. So it’s got altitude in a rainforest, and a sort of elevational bridge.

“There are also few endemics you can pick up in Colombo. The Ceylon Small Barbet, a sparrow sized bird, if you know what to look for you might even see it in the BMICH grounds.”

Spotting all 34 endemic birds in Sri Lanka is a hobby for many, and Wijeyeratne reveals that several tourists sometimes hope to see all of them in as a little as 10 days. For the Wijeyeratne, who is also the Chairman of the London Bird Club, this leads into one area in which he feels Sri Lanka could do better – namely the documentation of sightings in the country.

“In Europe people have phone apps, and they record their bird sightings through that, which goes into a database. This allows them the create bird maps, which are incredibly detailed,” he explains.

“A book in London used over a million bird records and it tells you in which one kilometre quadrant the bird has been recorded in.”

He adds that in India too, via the eBird India website, bird tracking is at a much higher level. Something he hopes Sri Lanka can aspire to going forward.

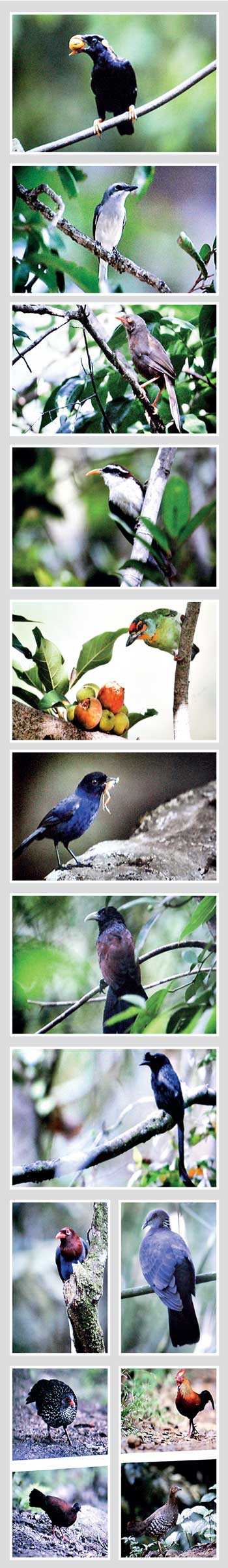

Pix by Ruwan Walpola