Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Saturday, 14 July 2018 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Dr. Kalana Senaratne

By Dr. Kalana Senaratne

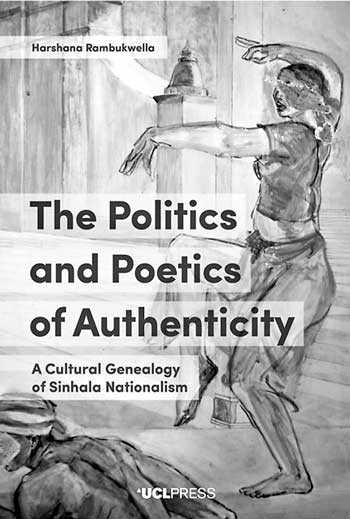

To a long list of works that engage with Sinhala nationalism, Dr. Harshana Rambukwella’s ‘The Politics and Poetics of Authenticity: A Cultural Genealogy of Sinhala Nationalism’ (UCL Press, 2018) is an important addition.

Freely accessible on the web, this relatively slim volume deals with the interesting notion of authenticity and its role in nationalist discourse. Ideas about authenticity or that which is considered authentic (a notion that gets translated as ‘ourness’ or ‘apekama’) have had very serious political implications. And as Rambukwella highlights in this book, authenticity lies at the very heart of the Sinhala nationalist discourse, especially in Sri Lanka’s post-independence history; and this could be said of the Tamil nationalist discourse too.

Rambukwella begins the book by arguing that it has been the enduring belief within Sinhala nationalist discourse that “something called apekama exists and that it is a national virtue with overarching unity”, though the precise contours of this may have changed over time. It is a notion which signifies the timeless character of the nation and the national/ethnic/religious identity and practices that get promoted in nationalist discourse. Thus the first two chapters explain the notion of authenticity, its relationship to primordial and modernist explanations of nationhood and the role authenticity plays in shaping the nationalist understandings of Sri Lanka’s past.

Authenticity is not an innocent notion, for “authenticity demarcates the boundaries of what is allowed in and what is left out.” This, in turn, easily translates into a “punitive discourse”, which “banishes and marginalises those who are ‘inauthentic.’” The book, without asking the question ‘what is a nation?’, proceeds to raise and address a far more interesting set of fundamental questions, such as: “Why is authenticity so central to nationalism? What kinds of conditions demand, sustain and reproduce it? Can we think of multiple and contending authenticities instead of one homogenous discourse?”

Rambukwella’s is a political intervention which “engages critically with the self-understanding and self-projection of Sinhala nationalism as a discourse that has ancient origins.” But in probing the why and how of authenticity, his key purpose is to see “how nationalist thinkers inhabit the nation and how they reproduce it.” This involves asking questions about the nationalists’ sources of authenticity, why they turn to authenticity and how “nationalist figures are reconstituted as icons of authenticity in post-independence Sinhala nationalism.”

In this regard, Rambukwella examines the life and work of three important protagonists: Anagarika Dharmapala, S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike and Gunadasa Amarasekara. Discussing each of them in three separate chapters (which form the core of the book), Rambukwella’s purpose here is to point to us how they conceived an authentic Sinhala nation, whether they really believed in what they said, and how later generations have understood and interpreted their role as promoters of an authentic Sinhala (Buddhist) nation, identity and socio-political system.

Dharmapala

One of the most interesting chapters of the book is dedicated to a discussion about Dharmapala. Rambukwella’s attempt is to untangle the ‘historical’ Dharmapala from the ‘ideological’ Dharmapala.

Was Dharmapala really interested and invested in a sense of authenticity? Rambukwella argues that the authenticity ascribed to Dharmapala is a shifting, malleable idea that arises from contemporary concerns about nationalism. Rather than seeing Dharmapala as a diehard nationalist, Rambukwella invites the reader to see him as “a man who strategically shifts position to operate in a translocal world.”

There are numerous ambiguities in Dharmapala’s writings, and Rambukwella points out that the vision of a pure and authentic Sinhala nation is visible when Dharmapala writes about the past, not about the present he lived in. Like many elites of his day, he saw himself as a “loyal subject of the British empire” (as more recent works about Dharmapala, such as by Steven Kemper, have shown).

Thus presenting Dharmapala as a nationalist hero who talked about an authentic Sinhala nation simplifies the thinking of a complex character. After all, Dharmapala was a man who distanced himself from Sri Lanka during his later life, wishing in the end to be born again in India to a noble Brahman family, which would enable him to become a Bhikkhu and preach the Dhamma to India’s millions.

S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike

The chapter on S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike is also a careful study of a number of writings through which Bandaranaike sought to discuss issues of authenticity. Again, like Dharmapala, Bandaranaike is known and remembered in Sinhala nationalist discourse as a great Sinhala patriot and a hero of decolonisation. But Rambukwella points out that his “relationship to a sense of authenticity was fraught with tensions and contradictions”, made more visible due to his public role as a politician.

The chapter on S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike is also a careful study of a number of writings through which Bandaranaike sought to discuss issues of authenticity. Again, like Dharmapala, Bandaranaike is known and remembered in Sinhala nationalist discourse as a great Sinhala patriot and a hero of decolonisation. But Rambukwella points out that his “relationship to a sense of authenticity was fraught with tensions and contradictions”, made more visible due to his public role as a politician.

For instance, in his Oxford-memoirs, Bandaranaike seeks to portray himself as being anti-colonial; though being thoroughly anglophile, privately. Next, Bandaranaike’s discourse on authenticity comes through his writings about the village, whereby he moulds himself as a politician who yearns for the return of the organic life, critiquing Western models of development.

The essence of Sinhala identity in his thinking lies in the village; with this village-based authenticity becoming central to the post-independence development discourse in the 1940s and 1950s. (In the final chapter of the book, Rambukwella discusses the ‘death’ or the end of the village as a site of authenticity, as a result of the Gal-Oya Irrigation Scheme, the Accelerated Mahaweli Development Programme and the Gam Udawa scheme).

Also interestingly, this chapter discusses the tensions that appear in Bandaranaike’s speeches about the Sinhala Only policy. Rambukwella argues that the reasons adduced by Bandaranaike to make Sinhala the official language and the fears he expressed about the threats confronting the Sinhala language and culture, are fears and anxieties that Bandaranaike was hesitant to personally endorse.

Bandaranaike was a politician who implicitly acknowledged that these claims of the Sinhalese have an element of exaggeration, claims from which he maintains an interesting distance. Somewhat strangely, these are then the men who have come to be celebrated, in later years, as the champions of the authentic Sinhala nation.

Dr. Gunadasa Amarasekara

The final protagonist in Rambukwella’s book is Dr. Gunadasa Amarasekara, one of Sri Lanka’s most prominent novelists and Sinhala nationalist ideologues. Unlike Dharmapala and Bandaranaike, one finds in Amarasekara’s work the clearest articulation and promotion of the notion of authenticity of the Sinhala nation.

Authenticity, in a sense, plays a foundational role in Amarasekara’s work. Discussing many of his novels and non-fictional works (which are rarely discussed in works published in the English language), Rambukwella points out how Amarasekara develops a grand socio-political narrative of Sinhala nationhood and identity.

Amarasekara’s dogged claim has been that there is an essential idea of Sinhala-ness that still survives, that authenticity is located in Buddhism and that there is a Buddhist socio-political system that has existed in Sri Lanka in antiquity, which has even survived the colonial encounter. According to Amarasekara, the reality of this structure, which cannot be erased, needs to be acknowledged; it is a structure that can be reproduced today.

Critical reading

Rambukwella’s book is neither the first, nor the last, to engage with the notion of authenticity in Sinhala nationalist discourse; though it may be one of the most lucid, and the most succinct, accounts about it. The form of critical reading adopted by Rambukwella is a popular one, especially among those of the Sri Lankan academia who are critical of Sinhala (Buddhist) nationalism.

This form of critical reading boldly depict many narratives of authenticity as constructed (and therefore, political) narratives; narratives which should never be viewed as natural, timeless, or obvious. At times, that which is called authentic may be seen to be of recent origin. It is a critique which liberates one from an uncritical and dogmatic attachment to nationalist discourses about authenticity.

Rambukwella’s reading is to be particularly admired, since he seeks to engage in an empathetic reading of authenticity while also suggesting that such empathy must be “tempered by a critical spirit that rises above the deep structural allure of authenticity and the sense of filial obligation that nationalism can engender.”

Also importantly, Rambukwella’s reading is an invitation to appreciate the complexity of the many figures that often get celebrated either as black or white (thus hated or loved) individuals in political discourse; a task that is never easy for many nationalists as well as their critics.

There is sometimes too much importance attached to these figures who, during their own time and age, may have been somewhat more ordinary and far more conflicted as individuals than many would wish to think. Dharmapala was one such individual, as Rambukwella suggests.

Two challenges

However, critical scholarship about nationalist narratives concerning authenticity (in this case, related to Sinhala nationalism) confront a number of challenges, two of which will be highlighted here.

However, critical scholarship about nationalist narratives concerning authenticity (in this case, related to Sinhala nationalism) confront a number of challenges, two of which will be highlighted here.

The first is that in contrast to nationalist narratives which promote a solid view of history and a sense of authenticity which has continued into the present, critical and deconstructive readings of history and personalities suggest that we simply cannot know for certain about the accuracy and solidity of such nationalist narratives. In other words, we simply do not know.

Instead of a single narrative then, critical scholarship ends up promoting multiple narratives and multiple ways of imagining the past as well as the present. (Though one certainly detects in critical scholars the tendency to consider their story to be the gospel truth).

But this raises the question of how to construct an alternative political vision that is inspired by critical scholarship. The problem here is that critical or revisionist readings of authenticity-narratives are largely attractive at an individual level; they are still unable to attract the attention of the masses or a considerable segment of society.

Transforming this critical sensibility into a political project that could convince wider segments of society is a daunting challenge, especially because the critics would need to re-construct at least part of the nationalists’ path that was earlier critiqued or de-constructed. In the longer scheme of things, what then is the political value of critical scholarship?

Secondly, it has become a popular trend in Sri Lanka to promote a certain kind of cosmopolitanism, best encapsulated in the famous ‘citizen-of-the-world’ identity, as the possible panacea to the troubles generated by nationalism. This, I believe, is how many who are sympathetic to Rambuwella’s work may proceed to think after reading his work; it is now the logical next-step in Sri Lanka’s critical discourse.

The promotion of this broader identity tends to happen in the following manner. It begins by showing that instead of believing in somewhat solid or singular identities with an authenticity worth cherishing, we need to imagine ourselves as entities which are a collective of a multitude of identities: a brother/sister, a father/mother, a Lankan/Asian, all in one singular self. In other words, we are never just a Sinhalese or a Tamil; we are that, and much more. From this, one moves into promoting a broad identity (in contrast to a narrow ethnic identity). Today, in Sri Lanka’s political discourse, this broad identity is often the identity of a being called the ‘citizen-of-the-world’.

It is an idea and an identity which of course has many merits. But there are also a number of problems associated with it. It appears to come more conveniently to those who have travelled the world: i.e. to a certain segment in society that can afford overseas-travel and to those who have just returned to Sri Lanka after retirement from long years of work overseas. It is also the case that nationalists know very well that there are many identities or identity-roles that they need to play in society; so the reminder that we are much more than just a Sinhalese or a Tamil is stale news to them.

Furthermore, the different identities we carry and the roles we play in society necessarily entail different and often conflicting attitudes and approaches, which may not be reconcilable. And this ‘citizen-of-the-world’ is often meant to represent the ideal of an unbiased creature, tolerant, able to take rational and considered decisions (especially on of serious matters of politics). But very often, they too are as politically biased as their nationalist-opponents, unable to acknowledge the relative merits of political concepts and structures that they are not fond of. How then are we to re-think basic questions about the nature of being, citizenship, and identity in an ‘inauthentic’ world? These are some of the questions that continue to confront us as we read Rambukwella’s book.

Authenticity

Narratives of authenticity will never go away, especially in Sri Lanka. As Rambukwella correctly points out, “the death of one kind of authenticity does not imply the death of authenticity itself. Authenticity has always been contested and reshaped.” Contesting problematic authenticity-narratives is a necessary task. But the issue with the notion of authenticity is that for a vast majority, this ‘ourness’ or apekama is also based on belief and faith. For many people, something is authentic because it is said to be so and also because they like it to be so; and no amount of alternative narratives would be able to unsettle that understanding.

The yearning for authenticity might lead people to believe in many (incredible) things. For instance, one would not know whether in a hundred years from now the Tamil people would come to believe that Sri Lanka was originally a Tamil land which therefore needs to be wholly, and not partly, liberated from the Sinhalese. Or, in a hundred years from now, the main challenge before the critics would be to point out why the Buddha was not essentially Sri Lankan as the popular narrative of their time proclaims.

One is not sure whether critical scholarship would have a transformative impact if and when that happens, but one may just be able to ensure at least then that the Dharmapalas of the future do not wish to be born again in India.