Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Saturday, 22 September 2018 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By D.C. Ranatunga

“Late one night in September 1959, after a tiring day at the General Assembly of the United Nations, I was enjoying some well-earned sleep at my New York hotel. Suddenly the bedside telephone rang and rang, until finally I took it up. I heard the words, ‘Our Prime Minister has been shot…’ I took in nothing more, as the voice trailed away. The caller was Sir Claude Corea, our Permanent Representative at the UN and the head of our delegation.

“There was a sudden sense of emptiness and loneliness, and no further sleep. One felt that things have changed for ever. Previously, as Ceylonese, we had always held our heads high in international gatherings. Violence was something that erupted in other countries, never in ours. On that day our optimistic serenity was badly shaken, and I don’t think it had ever come back.”

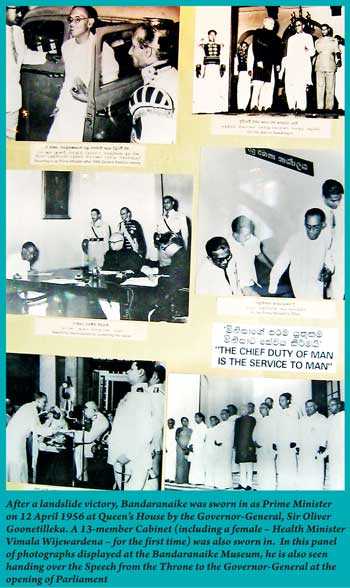

The narration is by Sam Wijesinghe, Secretary-General of Parliament in his book, ‘All Experience – Essays and Reflections’ (2001) writing about S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike (1899-1959), Sri Lanka’s fourth Prime Minister (1956-59), after D.S. Senanayake, Dudley Senanayake and Sir John Kotelawela.

In four days, the country will be commemorating his 59th death anniversary.

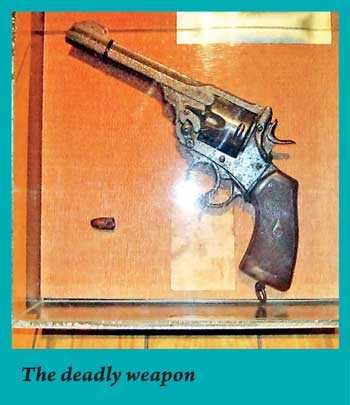

I vividly remember the fateful day, 25 September 1959. A little after I got to office – I was then a reporter on the ‘Dinamina’ – we got the news that the Prime Minister had been shot by a person in saffron robes, believed to be a Buddhist monk at his residence, ‘Tintagel,’ at Rosmead Place.

I was in the team of reporters assigned to run around and follow his condition, and details of the incident. The accent was on the General (now National) Hospital where he was undergoing surgery. In and around the PM’s residence was out of bounds and the alleged assassin had also been taken to hospital following a gun injury by the police constable who was on duty at the PM’s residence. (He was, however, at the gate and until someone alerted him, he didn’t know what had happened).

Being the ‘People’s Prime Minister’, he never expected anyone would harm him and freely met people who came in the morning and sat in the verandah pending his arrival before going to office.

Everyone was keen to know about the condition of the PM and the radio was the only medium available, apart from word of mouth. There were two afternoon English newspapers – ‘Times of Ceylon’ and ‘Ceylon Observer’ – being published at the time and the people anxiously waited for the papers that day.

The papers and the radio reported that the PM had appealed from his hospital bed that a man in yellow robes had shot him and called on the people to stay calm.

By the time the early editions of the following day’s morning newspapers went to print, the news was that the PM was fighting for his life. The ‘Daily News’ headline was: “Premier still not out of danger”. His operation had gone on for five hours and at one stage his heart had stopped beating, the news story said. After a tiring day, while we got back home, the night staff kept watch ready to print a special edition if there was the need.

The next day being Saturday, our off day, I heard the news over the radio in mid-morning that the Prime Minister had passed away.

On Sunday (working day for the staff of morning papers), while we had to follow up on funeral arrangements and visitors turning up at the PM’s residence, it was equally important to see how the Cabinet was reacting.

In the absence of C.P. de Silva, Leader of the House and senior minister who was ill and was undergoing treatment in London, next in line Education Minister Wijayananda Dahanayake had been appointed as interim head of the Government. There were no houses given to ministers then and being a bachelor he used to stay at ‘Sravasti,’ the MP’s hostel.

In the absence of C.P. de Silva, Leader of the House and senior minister who was ill and was undergoing treatment in London, next in line Education Minister Wijayananda Dahanayake had been appointed as interim head of the Government. There were no houses given to ministers then and being a bachelor he used to stay at ‘Sravasti,’ the MP’s hostel.

On Sunday morning he had moved to Temple Trees, the PM’s official residence which Bandaranaike used only for official functions, and he was ready to meet reporters. The ‘Daily News’ News Editor, Gerald Delilkhan and myself rushed to Temple Trees and we were cordially received by him. He had also given an appointment to a BBC team. Those were the 35mm news reel days and when they came, he wanted both of us to join him and walk on the lawn while the cameraman did the shooting.

The PM’s body was first brought to his residence and the next day to Parliament (at Galle Face) and people from all over the country thronged to pay their respects. Three years earlier, on the first day that Parliament met after the Mahajana Eksath Peramuna victory at the 1956 general election, people rushed to the same place and even occupied the Speaker’s chair claiming it was the ‘Ape Aanduwa’. Massive crowds turned up at the funeral at Horagolla and when we went to cover the proceedings, we had to walk several miles after parking the car, which itself was not easy because of the crowds. They walked silently as a mark of respect to a great leader and statesman.

Peaceful revolution

In his article, Sam Wijesinghe writes about the 1956 ‘peaceful revolution’: “His election victory ushered in a new era in the history of our land, registering a realisation by the voters of their own strength that had remained dormant for 25 years that had passed since adult franchise was introduced. Bandaranaike’s view was that what happened in 1956 was a peaceful revolution brought about by the votes of the people.

“Amongst the various factors that contributed to this result was the emerging confidence of the masses to overthrow a regime which, under the guise of freedom, was really continuing a system of ‘colonial’ thought and action primarily concerned with the preservation of vested interests. It paid scant attention to the needs of the people to whom independence had meant little  more than a mere change of rulers. So what happened in 1956 was seen as a victory for the people, a victory of progress against reaction.

more than a mere change of rulers. So what happened in 1956 was seen as a victory for the people, a victory of progress against reaction.

“However, Bandaranaike was quite candid in admitting that his Government was not perfect, and would not be able to do everything that the people expected. And the difficulties were compounded by the sudden release of various impulses and urges that had been suppressed by previous regimes and now burst out in undisciplined incoherence.”

Referring to a remark he had once made that “we will cross the bridge when we come to it,” Sam W comments: “Bandaranaike indeed might have managed to manoeuvre the country across that bridge. Unfortunately, indeed tragically, he was one of the first victims of the whirlwind, and his life was not spared for him to make the crossing.”