Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Saturday, 9 November 2019 00:17 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By D.C. Ranatunga

Sri Lanka’s foremost sculptor in recent times, Tissa Ranasinghe is no more. He departed at the ripe age of 94 having spent the better part of his life in England – both as a student and a professional. He visited Sri Lanka on and off particularly when his work was exhibited. His name, however, comes up whenever his students exhibit their creations.

Tissa R hit the headlines in mid-1957 when as a student just out of Chelsea School of Art he offered to do a statue of D S Senanayake, first prime minister free of charge if the required material was made available, in place of what the ‘Ceylon Observer’ called a “monstrosity” in an editorial referring to one done by a British sculptor. Tissa’s creation can be seen to-date in the premises of the Presidential Secretariat – then Parliament premises.

While the British sculptor who had never seen Senanayake had based his work on photographs, Tissa had known him personally during four years when he was an agricultural inspector  prior to his studying art. He recalled seeing the Prime Minister “in bush coat beaming with pleasure over a field of bronzing paddy in the dry zone at Mahiyangana and as an ‘upasaka’ at village functions and important ceremonial occasions”.

prior to his studying art. He recalled seeing the Prime Minister “in bush coat beaming with pleasure over a field of bronzing paddy in the dry zone at Mahiyangana and as an ‘upasaka’ at village functions and important ceremonial occasions”.

The ‘Observer’ collected the Rs. 14,000 required for the materials from the public and after many bureaucratic delays the job was done.

Ironically, on the day the statue was being unveiled, the sculptor was not even invited. “I was in the crowd until an Inspector of Police asked me what I was doing in the crowd and took me to the Governor General,” Tissa once recalled. In fact, when he had heard that Governor General, William Gopallawa was going to open it he had met the secretary of the UNP, the party founded by DSS, and suggested that they should get one of the oldest colonists from Gal Oya to unveil the state, Failing which get five children from the different communities to collectively to do it.

Thanks to one time journalist, painter, author, designer and graphic artist Neville Weeraratne, his story along with heaps of photographs of his work has been recorded in ‘The Sculpture of Tissa Ranasinghe’. Neville, himself a ’43 Group artist had known Tissa for over. He has delved into a lot of material to make the book a most worthy publication done by The National Trust, Sri Lanka.

Hailing from Yogiyana near Sandalankawa – the place made famous by the pioneer of the cooperative movement Vincent Subasinghe, Tissa belongs to a traditional Sinhala Buddhist rural family. Being from the coconut and paddy country, agriculture was naturally in his blood which possibly made him join the School of Agriculture in Peradeinya and obtain a diploma in 1946. He was then 21. He joined the Botany division in the Department of Agriculture and it was a comment made by his head about a hand drawn calendar Tissa sent him that encouraged him to think of studying art. He joined Heywood, the Government College of Fine Arts where renowned painter J D A Perera was the principal.

“Tissa was encouraged to paint with vigour and certain bravura inspired his work. He painted with great confidence. His ‘Rodiya Woman’, for instance is painted with all the panache of a salon portraitist. At all times he remained a draughtsman with a keen eye to proportion and balance,” Neville writes.

Although he got his diploma in painting after the three-year course (in 1952), J D A Perera encouraged him and another student George Bevan to move over to sculpture. They were required to use clay as one of their materials. While Beven didn’t like the idea and left, Tissa decided to try it out. He had for his instructor Rathi (Mrs D B) Dhanapala, herself a very accomplished sculptor.

“In accepting J D A Perera’s inspired suggestion Ranasinghe took upon himself a responsibility he probably did not realise at the time. He was to become the first important sculptor to work in Sri Lanka since the stone carvers of Polonnaruwa laid down their chisels and their mallets at the Gal Vihare in the 12th century. J D A Perera’s judgement of Tissa’s capacity to undertake this responsibility must quite well have come from his showing of a special gift for portraiture as seen in a number of heads done in clay in 1952 while studying at the College of Fine Arts. These were not mere amateur efforts but studied and highly successful works,” Neville sums up his early days.

After obtaining a diploma in sculpture Tissa applied for a government scholarship to study in Britain but failed to get one. He then went at his own expense in 1954 with the help of his brothers and joined the Chelsea School of Art where a year later he was awarded the first prize in sculpture at the annual exhibition. In 1958 he was awarded an UNESCO scholarship to complete his studies and travel in Europe for three months visiting galleries and museums.

He began participating in numerous exhibitions where he won the accolades of renowned art critics.

Recalling the days Tissa returned to Sri Lanka with wife Sally, Neviile wrote about “the stocky, bearded sculptor with closely-cropped hair in his habitual garb of bush shirt, short trousers and chappals”, staying in an annexe of a house in Bambalapitiya. “They were the most comfortable clothes for a warm, tropical and humid atmosphere. He seemed the perfect example of a young man going about his business without ostentation. That was, indeed, the nature of the man. It was the nature of his business that made the difference,” Neville wrote. In fact, when I used to meet Tissa much later he was always in that kit.

Tissa set up his studio there and it did not take long for it to get filled with heads of an array of the best known personalities in this country. They ranged from Professor Senerat Paranavitana and Martin Wickremasinghe to H W Rupaisnghe and Tower Hall actors Romulus Silva and Annie Boteju to theatre guru Arthur van Langenberg and many more. Neville thought that he selected his subjects based on their unique physical characteristics, their looks, their physiognomies, just as much as he was conscious of their contribution to the culture of our times.

Neville considered Tissa a well-rounded six-dimensional person, like his work: “Height, width and weight apart you had to consider his spiritual, moral and intellectual attributes. Tissa was fifty years ago, as he is now, a modest man. He is a good-humoured and simple human being who enjoys a bit of fun but never, as far as I can recall, at the expense of his vocation as an artist. He has applied himself to his chosen art with religious zeal.”

Among the much-talked about pieces of sculpture by Tissa are the Buddha statues on the themes ‘The Renunciation’, ‘Enlightenment’ and ‘Self-mortification’. With his Buddhist background, Tissa seemed to have taken a special liking in sculpting the Buddha. He sculpted Arahant Mahinda and Theri Sanghamitta as well The Buddha statues are seen all over including the Washington Buddhist Vihara and the Commonwealth Institute of London.

Whenever the government wanted to gift something special to an international institution, it was Tissa who was requested to oblige. Among such gifts ‘The Peaceful Resolution of Disputes’ – a 4’x2’ bronze relief gifted to the International Court of Justice at The Hague stands out. It is based on the Buddha’s visits to Nagadeepa and Kelaniya.

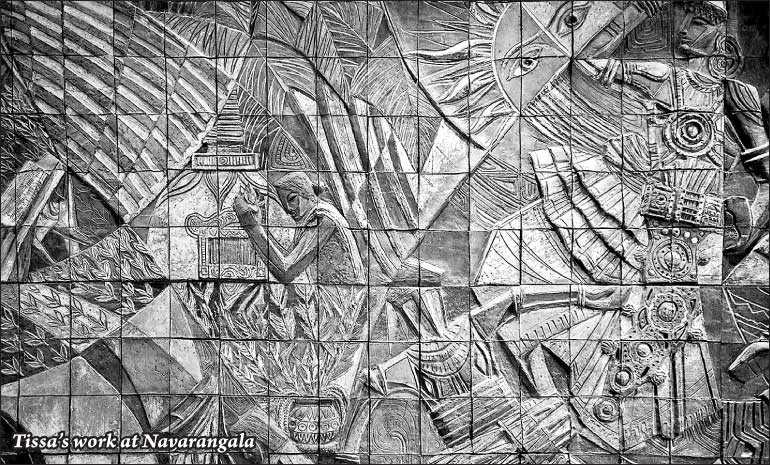

I was personally involved with the Observer-sponsored Navarangahala project when Royal Junior principal H D Sugathapala (he was then chairman of the Sinhala Drama Panel of the Arts Council during the golden era of Sinhala theatre) decided to build a spacious theatre where Sinhala dramatists could perform. He commissioned Tissa to do a bas-relief in terracotta tracing the history of theatre in Sri Lanka. It turned out to be a unique 40’x8’ creation which adorns the front wall of Navrangahala.

Tissa was principal of the College of Fine Arts for a brief period (1969-January 1971) when he resigned in disgust when he could not deliver what he wanted he wanted to do for the benefit of the students. He then decided to move out to London where he worked in the foundry of the Royal College of Art gaining the plaudits of colleagues, students, critics and an enthusiastic following. Yet he never forgot that he was the Sinhala ‘gamaya’ from Yogiyana.