Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday, 13 July 2019 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Chandani Kirinde

By Chandani Kirinde

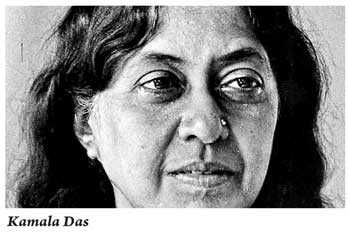

Kamala Das (1934-2009), the trailblazing Indian English poet, is known for her themes exploring women’s sexuality, martial and domestic strife, and human rights, among others. She wrote both in English and Malayalam and attracted her fair share of controversy in her lifetime, particularly with the release of her autobiography titled ‘My Story’ in 1976.

During the period 1982-’84, Das was a frequent visitor to Sri Lanka after her husband was offered a consultancy with a bank in Colombo. It was during this period that the ethnic riots took place in July 1983 and the poet, caught up in the ensuing tragedy, wrote about the troubling times in her poetry.

While it’s 36 years this year since this dark chapter in the country’s history unfolded, some of the poems Das wrote on her experiences capture the images of a city on fire, the fear among people and the denial by some of what had taken place.

As the riots engulfed Colombo for a week, Das, in her poem ‘Smoke in Colombo,’ brings to life the scenes through her poetry.

“On that last ride home, we had the smoke

Following us, along the silenced

Streets, lingering on, through the fire

Was dead then in the rubble and the ruins

Lingering on as milk ligers on

In udders after the claves are buried…”

After the riots were over, the city had changed forever and in ‘After July,’ Das gives a glimpse into how people’s lives changed.

“After July, in Colombo there were

No Tamils in sight, no arangetrams

Were held in the halls, no flower-sellers

Came again to the door with strings

Of jasmine to perfume the hair.

Like rodents they were all holed up in fear…”

Das herself struggled to fit in with the expatriate community after the riots, writing that “despite my nut brown skin,” her attempts to merge well with the expatriates had failed. She socialised with her Sinhalese friends and in the poem ‘The new Sinhala Film,’ she captures the attempts by her friends to deny the dark events that had taken place in their city and shield themselves by superficial means.

“…The close friends I have among the Sinhalese

Wait till dusk to visit me and they wisely

Talk only of the new cinema as though

Nothing has happened in the recent past but films…”

The poem concludes this way:

“When at last we return, if at all we do,

Dodging the speeding Army truck or perhaps

The accidental shot, we shall not ever

Discuss the disgusts of the past but shall only

Talk brilliantly of Dharmasiri Bandaranayake’s

‘Thunveni Yamaya’ and ‘Arukgoda’s Monaratenna…’”