Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday, 14 October 2017 00:52 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

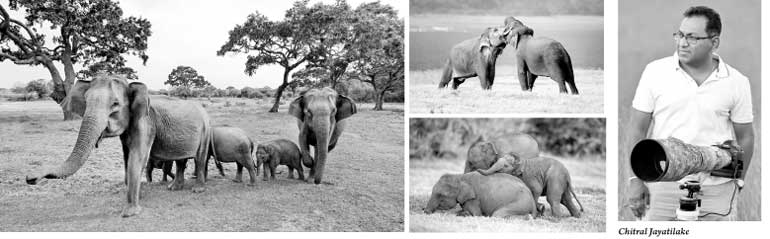

By Chitral Jayatilake

By Chitral Jayatilake

The island was known to be home to elephants in excess of 12,000 during the 19th century and during the British-governed Ceylon. At least until 1830, elephants were widespread in the island, covering the hill country in considerable numbers. The British administrators encouraged shooting elephants and rewards were given for killing them, removing the burden of having to deal with a large pachyderm in a land they needed to cultivate for coffee and thereafter tea plantations.

Sri Lankans almost venerate tuskers and for thousands of years, they have captured and domesticated them, taking them out of the wild gene pool. Then there was trophy hunting by the British which also accounted for many of the tuskers being removed from the wilds, thus, further causing the selective loss of the tusk gene, that has resulted in the vanishing of tuskers among male elephants in the island. It’s intriguing to compare most Indian males carrying ivory in comparison to just about 6% of our male elephants blessed with tusks.

Individuals such as Major Thomas William Rogers during his administrative period in the Uva Province was entrusted to build roads connecting Nuwara Eliya to Badulla. During his tenure as Assistant Government Agent between 1834 and 1845, it is on record that Major Rogers shot over 1,400 elephants. This number is indeed astounding, but it is also said that marauding herds would decimate cultivations of rural Sinhalese villagers and Rogers would be called upon to shoot elephants bringing relief to the villagers. Ironically, Major Rogers died after being struck by lightning on 7 June 1945 while at Haputhale Rest House welcoming his superior Government agent R.C. Buller.

As the wet zone was converted to cash crops, the populations there died out while the populations in the dry zones flourished until the irrigational diversions in the early eighties began to interfere with their traditional movements and pathways.

In recent history, the accelerated Mahaweli development project stands as the largest disruption to elephants. The rapid diversion of the great Mahaweli River that cuts across much of the elephant country and clearing immense areas for creating cultivable land that exploded with villagers since the early eighties, fuelled the human-elephant conflict better known as the (HEC) in Sri Lanka.

More ill-planned land distribution in the Southern, Uva and Eastern Provinces have escalated this conflict while the North Central and North Western provinces have shown an incredible spike, taking a heavy toll of life among both man and elephants. While elephant habitats across dry zones are still contiguous, they encounter pockets of villagers that are springing to life adding fuel to the fire spreading the HEC further.

Gathering – A classic animal spectacle

In this backdrop of events, and the numerous failed elephant drives conducted by the Department of Wildlife Conservation due to public and political pressure, that has created much strife and disruption of herds, we are amazingly lucky to still boast of possessing almost 10% of the global Asian elephant population. In an island home to almost 21 million people, having almost five thousand elephants in the wild defies logic, but we have this magic that makes our natural world richer and for a foreign visitor, simply an unforgettable experience.

The gathering of elephants has taken place in many dry zone locations centric to water and adequate fodder. Handapanagala was one such location during the early nineties. Thereafter, a similar gathering was highlighted around the Minneriya Reservoir built by King Mahasen covering a spectacular 8900 hectares. Soon, this ancient tank (reservoir) built by a wise king in the 3rd century AD would become the staging ground of the spectacular Gathering of Giants.

During the peak dry season in the Central Province of Sri Lanka, as the water is let out for cultivation from the large reservoirs like Minneriya, the reservoir beds turn into lush grasslands, triggering various elephant herds to begin their seasonal movement towards the receding tank beds in search of excellent grazing. Seasoned matriarchs would lead their herds often numbering 10-18 elephants towards this location of plenty, where receding waters of the reservoir expose fertile soil in which fresh grass grows abundantly, inviting the pachyderms.

A ring of shrub forest that prevails beyond the open grasslands just speaks perfectly to the herds that arrive here by mid-June and peaks by August of each year. In the dry zone where annual rain fall is less than a 1000 mm of rain, the lush grass becomes the governing factor to most animals and the elephants keep congregating towards this magical setting exceeding 300 individuals by September.

Amazingly, while Minneriya caught the attention of the world after being declared by Lonely Planet as the 6th Greatest Animal Spectacle in the World, there were other reservoirs in the dry zone hosting several more gatherings among which ‘Kalawewa’ and ‘Kaudulla’ ranks very high to see elephants mid-year.

The magic at Minneriya breaks up with the first rains from the north-east monsoon falling by the second week of October. The rains trigger the elephants to move from flooding plains at Minneriya towards Kaudulla National Park. As the Gathering shifts its location, so does the monsoon escalating into a torrential down pour breaking up the many herds that forms this spectacle, scattering them towards their original feeding grounds across the North Central Province of the island.

Today, this seasonal event has become the centre of attraction to almost all visitors to the cultural triangle, thus, creating livelihoods for thousands of villagers. But this magnificent occurrence will be threatened in the event the Minneriya Reservoir is used as a stock tank for cultivation. We hope that the authorities will ensure the preservation of this amazing Gathering of Giants that has now become a signature event of the island’s wildlife calendar, generating much-needed revenues to the local economy and focusses the world’s spotlight on this island nation that proudly hosts the sixth greatest animal event of the world.

(This article first appeared in ‘Living Free’, a 196-page book of wildlife photographs by two of the country’s best-known shutterbugs Chitral Jayatilake and Vimukthi Weeratunga.)