Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Saturday, 30 December 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Vimukthi Weeratunga

A region of mystical beauty often described as strange, the central highlands of Sri Lanka was declared a UNESCO world heritage site in 2010. An excellent hike, often dotted with adventurous holidaymakers, the serial property comprises of three components; Peak Wilderness Protected Area, Horton Plains National Park and the Knuckles Conservation Forest. As stunning as the rugged landscape is to the discerning eye, so are the exceptionally populated endemic species of flora and fauna.

Horton Plains National Park is an undulating plateau with an elevation of more than 2000 metres; a land of misty grasslands marked with patches of umbrella-shaped montane forests. Nestled between Sri Lanka’s second and third highest mountains; the Kirigalpotta (2395m) and Totupolakanda (2359m), the park offers panoramic views, especially at the famed ‘World’s End’, an escarpment with a vista of hills and valleys at a drop of more than 880 metres that is both fearsome and seemingly infinite.

Horton Plains lies at the eastern extremity of the Wet Zone and experiences a subtropical monsoon climate, with a mean annual temperature of 15oC and mean annual rainfall of 2150 mm. The weather is dominated by persistent cloud cover and strong winds, sometimes gale-force, during the south-west monsoon. The driest months are January and February, when temperatures may reach 27oC. (Pethiyagoda (ed) 2012)

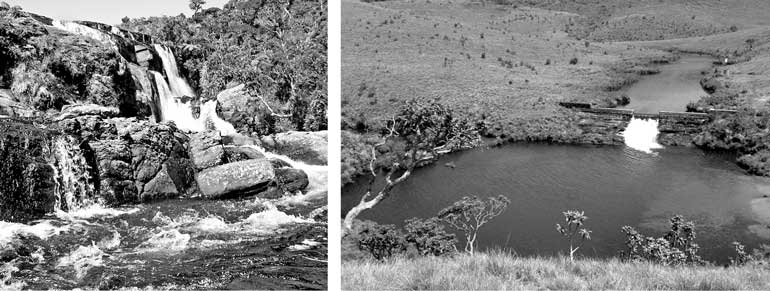

Situated in the Nuwara Eliya District, within the Central Province, Horton Plains and its surrounding forests – play an invaluable role, as the catchment area of almost all Sri Lanka’s major rivers. Declared a nature reserve on 5th December 1969, Horton Plains was upgraded to national park status on 16th March 1988, covering 3109 ha due to its unique watershed and biodiversity values.

Originally known as “Mahaeliya”, in the mid-19th century, Horton Plains was re-christened after the British Governor Sir Robert Horton. Even then, it was protected under the administrative order released in 1873, which prohibited the clearing of forests above 5000 feet (DWC 2007). The plains are of astonishing beauty and contains most of the endemic plants and animals that reside in Sri Lanka’s montane zone.

The recent archaeological findings unearthed evidence that the origins of Horton Plains is directly dated to the pre-historic Mesolithic culture in Sri Lanka. Archaeological evidence shows that major environmental changes have occurred during the last glacial period 24,000 - 18,500 years ago. Studies of pollen and spores led us to the harsh, dry environment that existed during that time, giving further evidence of the hunt-gather culture of the pre-historic man.

Fossilised evidence which was found in pollen suggests that the oat and barley farming began during the post glacial period 17,000 - 16,000 years ago. The oat and barley plants found in the region are a mere reminiscence of that fact. The grasslands with montane perimeter forests are indeed one of the few agricultural legacies left by the pre-historic man in the Horton Plains (Premathilake & Risberg 2003).

A larger portion of Horton Plains comprises of grassland with gentle slopes forming the high plateau. Like patches on a canvas, the bright rhododendrons scattered among the plains are both common and striking. The recently widespread dwarf bamboo (Arundinaria densifolia) flourishes on valley basins, surrounding depressions and small streams. On the western slopes of Horton Plains National Park are the montane cloud forests which is a touch of heaven as they majestically rise to the skies; a safe haven for many endemic and threatened species of Sri Lanka.

Research shows that out of approximately 353 species of woody plants in the plains, 119 are endemic to Sri Lanka and 14 under threat of extinction. Large numbers of epiphytes, orchids, mosses, and ferns species add special character to the floral diversity in the plains due to the high moisture condition throughout the year. Of the 188 species of orchids recorded within the island, 12 species are from Horton Plains; four of which are endemic to Sri Lanka (Pethiyagoda (ed) 2012). Several species of strobilanthes found in the plains and some species of flowers are of a lifespan of 10-13 years. Of the 31 species of strobilanthes found in Sri Lanka, 26 of them are endemic to the island. Many species of strobilanhes are found in the undergrowth of the cloud forests.

Considering the diversity of species hidden within its boundaries, the Horton Plains is a necessity that demands supreme protection (Pethiyagoda (ed) 2012 and Athugala et.al. 2014).

Wet and humid conditions in Horton Plains provide an excellent habitat for many species. However, the crystal clear streams of Horton Plains are free from indigenous fresh water fish species due to the harsh, cold temperatures, though it’s ideal for the rainbow trout. This fish was introduced to Horton Plains in 1882 for sport fishing. The waters are also a haven for endemic shrimp Lancaris sunghalensis and several species of fresh water crabs that have restricted distribution found here (Pethiyagoda 2012).

The amphibians in the region are also highly unique, out of which approximately 90% are endemic. Of the 11 species of amphibians recorded, ten are endemic and are flagged for threatened existence. Among the shrub frog species, the Horton Plains shrub frog can also be found in the peripheral areas of the park. Among the threatened amphibians of Sri Lanka, leaf nesting shrub frog, small-eared shrub frog, Schmarda’s shrub frog, Horton Plains shrub frog, and Frankenberg’s shrub frog are found on the plains (Manamendra-arachchi 2006).

Only nine species of reptiles have been recorded from Horton Plains out of which eight are endemic to the island. Two relict and endemic agamid lizards, namely rhino-horned lizard and pigmy lizard have been seen in the region. Only two species of snakes have been recorded in Horton Plains as the cold climate is not the most favourable to the sustenance of these slithering evolutions of the reptile family. Neither is poisonous and they are considered fossorial species that live most of their time in the soil layer (Somaweera 2006).

A variety of micro climatic conditions has created ideal conditions for many bird species recorded in this region. The plains provide critical habitats for many endemic and threatened bird species while a total of 81 species have been recorded in Horton Plains, of which 18 are endemic to the island. Horton Plains shelter not only locally-threatened but also globally-threatened species, namely – Sri Lanka whistling thrush, Sri Lanka wood pigeon and Sri Lanka blue magpie (MoE 2012).

The grassy plains and cloud forests of Horton Plains are considered as prime habitats to conserve the threatened and endemic mammals of Sri Lanka. A total of 28 mammal species have been recorded in the region of which 11 are endemic. The Horton Plains provides suitable habitats for endemic and threatened shrews, namely Sri Lanka highland shrew, Gordon’s pygmy shrew, Kelaart’s long-clawed shrew and nelu rat.

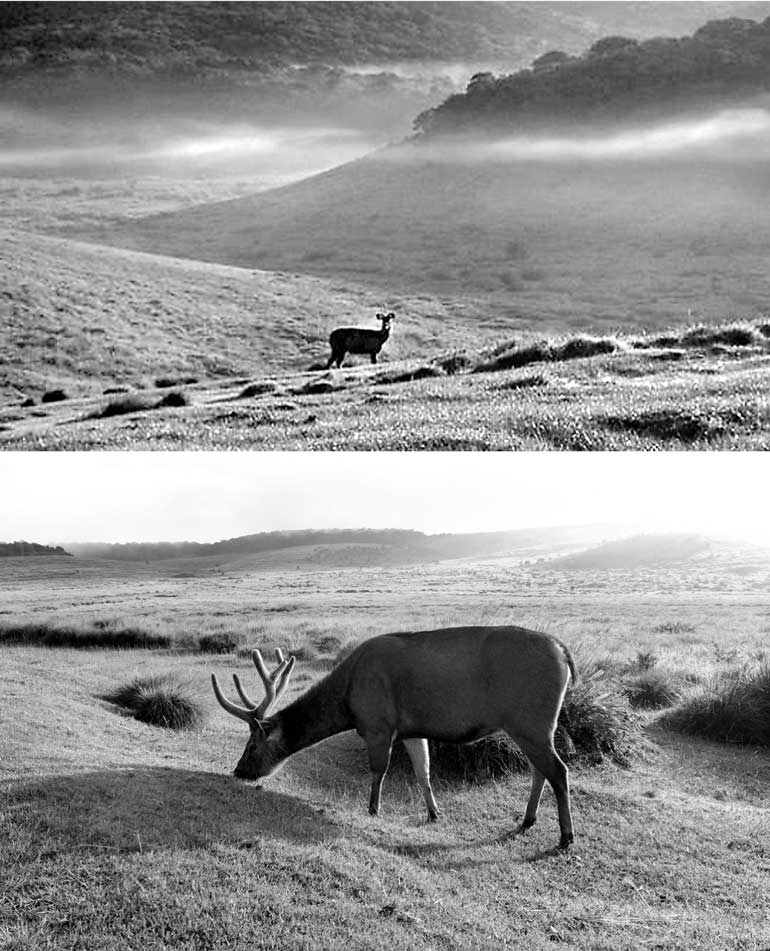

Among the carnivore species are the rusty-spotted cat, fishing cat, otter and the largest cat of Sri Lanka, the mighty leopard; and is also one of the prime locations to observe a large number of sambhur (Cervus unicolor). Due to the abundance of extensive grasslands ideal for feeding, and adjoining forest patches for protection, the plains of heaven hosts flourishing numbers of sambhur deer which is quite an amazing sight for the visitors.

(This article first appeared in ‘Living Free’, a 196-page book of wildlife photographs by two of the country’s best-known shutterbugs Chitral Jayatilake and Vimukthi Weeratunga.)