Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Saturday, 17 February 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lankans could face the shocking reality of elephants becoming extinct in just 27 years

By D. C. Ranatunga

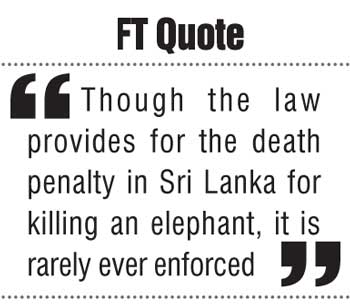

Elephants in Sri Lanka will vanish by 2045 - just 27 years from now. You don’t need to be an animal-lover to be shocked when you hear this. We all love the elephant. Seeing an elephant walking on the road, anyone will stop and look. It is rare that a ‘perahera’ even in a remote village temple is held without an elephant. The success of a major procession like the Kandy Dalada Perahera, Bellanwila Raja Maha Vihara Perahera or the Gamgarama Navam Perahera takes into account the number of elephants taking part.

It was the Auditor General who has said recently that his department has estimated that the elephant population of Sri Lanka will die out by around 2045. “Around 250 elephants die a year on average and after we compared that number with birth rates, it’s quite likely that our elephant will be extinct in another few decades. Our Wildlife Department however, does not seem to care,” Auditor General Gamini Wijesinghe was quoted as saying at a media briefing.

Not one but two shocking statements, one may say. The disappearance of this majestic animal is bad enough. To be told that the Wildlife Department doesn’t care is appalling. It’s even worse that there had not been a response from the Department or the Ministry.

If we are to trace the history of the elephant in Sri Lanka, the elephant played a prominent role during the time of the Sinhalese kings. There is reference to the ‘mangalahatti’ – the state elephant on which the king rode – in Sinhala literature of the 3rd Century BC. The Dutugemunu-Elara conflict highlights how to two kings fought using their elephants.

From the earliest times, there had been a significant demand for the Lankan elephants from other countries. Tennent (1861) says that the export of elephants from Ceylon to India had been going on without interruption from the time of the first Punic War. India wanted them for use as war elephants, Burma (now Myanmar) as a tribute from ancient kings and Egypt probably for both war and ceremonial occasions. There is evidence of elephants being exported to Kalinga by special boats from about 200 BC from the port of Mantai which was a major port in ancient Sri Lanka.

Problems relating to elephants have been escalating over the past several years. The human-elephant conflict has led to multiple elephant killings in addition to which there has been merciless poaching to collect and sell elephant tusks. An elephant affectionately known as ‘Dala Puttuwa’ (due to its crossed tusks) was killed a few months back and its carcass was later found with a bullet wound to the skull. A few persons have been arrested over the incident.

Though the law provides for the death penalty in Sri Lanka for killing an elephant, it is rarely ever enforced.

The killing of elephants is not something that was started in recent times. After the European powers occupied the country, it was reported that the Dutch exported elephants from Jaffna. Then after the British captured the Kandyan kingdom and gradually started plantation crops, hunting became the favourite sport of the British officials and planters. “Men such as Major Rogers (Assistant Government Agent, Badulla 1834-45) and Sir Samuel Baker have left behind a legendary trail of slaughter hard to beat in any country. The killings were counted in the thousands,” says Dr C G Uragoda in his ‘Wildlife Conservation in Sri Lanka’ (1994) published in connection with the centenary of the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society of Sri Lanka. When Major Rogers was suddenly killed by lightening at 41, it was estimated that he had killed 1,200 elephants during his 12 years at Badulla.

This is how the incident has been recorded by Dr Uragoda: “On 7 June 1845 the Government Agent in Kandy, accompanied by his wife, arrived in Haputale on a tour of inspection. Rogers rode to Haputale from Badulla. While at the rest-house there was a thunderstorm which kept them indoors. When Rogers stepped out to see whether the rain has ceased, there was a sudden flash of lightening which, entering through the steel spur of his riding boot, killed him instantaneously.”

When royalty visited

Dr Uragoda’s says that when royalty visited the country, nothing seems to have pleased them more than the offer of an elephant hunt which was regarded as an act of hospitality with a special local flavour. Among such visitors were Prince Friedrich Wilhelm Waldermar of Prussia (1844), Archduke Ferdinand d’Este – heir to the Hapsburgs’ Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Prince of Wales – who later became King Edward VII and the Crown Prince of Germany. The Archduke had bagged an elephant at Kalawewa in 1893 and two souvenirs – a leg and tail of the elephant had been exhibited at Kanopaste Castle in Czechoslovakia. When the Prince of Wales came in 1875 and went on a hunt, an enraged elephant had charged at him and he had been saved by two local aides.

Apart from hunting elephants, reference is made to chieftains organising the capture of elephants using ‘Panikkans’ – professionals in the art of capturing elephants in a most cruel way. Barriers and enclosures were built to keep the elephants once they were captured. These were known as ‘kraals’. Dr Uragoda says that these were elaborate showpieces which at times assumed a festive air. “Elephants were driven into the stockade where they were noosed one by one and then subdued. Success of a kraal was measured by the number of elephants captured but these numbers did not take into reckoning the animals which died or were maimed,” he states.

Jayantha Jayawrdene in his ‘Sri Lanka’s tame elephants’ (2013) says that during the time of the British, the first owners of elephants were the chieftains of the Wanni district. They were either given or allowed to keep some wild elephants. The chieftains had to give a specific number of elephants each year as tribute to the British government. Many elephants were captured by the kraal (‘ath gaala’) method when a herd of elephants are driven into a large enclosure (‘gaala’) and then captured. As for the capture of elephants, he outlines several methods: Using a female decoy, noosing – head noose, tree noose and ground nooses, drugged food – opium introduced to pumpkins and melons which were then placed on their trail, pitfalls and kraall.

Jayantha Jayawrdene in his ‘Sri Lanka’s tame elephants’ (2013) says that during the time of the British, the first owners of elephants were the chieftains of the Wanni district. They were either given or allowed to keep some wild elephants. The chieftains had to give a specific number of elephants each year as tribute to the British government. Many elephants were captured by the kraal (‘ath gaala’) method when a herd of elephants are driven into a large enclosure (‘gaala’) and then captured. As for the capture of elephants, he outlines several methods: Using a female decoy, noosing – head noose, tree noose and ground nooses, drugged food – opium introduced to pumpkins and melons which were then placed on their trail, pitfalls and kraall.

The last kraal was held in Panamure in 1950 which led to the killing of an elephant to clear the way for the noosers. There was a huge uproar and even a Sinhala song was composed about the tragedy. A few years back, a Sinhala play was staged around the Panamure disaster.

By that time the Wildlife Protection Society had launched the ‘Save the Fauna’ plan which received an unexpected fillip by the public outcry against the killing of the elephant. In 1952 the Society set itself the goal of totally preventing the capture of elephants by private individuals and banning their shooting except under special circumstances. The Society made representations at the general assembly of the International Union for Conservation of nature and Natural Reserves and a resolution passed which stated: “The assembly recommends that particular attention should be given to the preservation of the Ceylon elephant, traditionally associated with the country’s history and also the dugong, an animal reported to be in grave danger of extermination.”

According to statistics quoted by Dr Uragoda, the average number of elephants shot or captured by license was 97 a year over the six-year period ending 1950. It was estimated that with deaths there was an average loss of 172 animals each year, a loss that breeding could not catch up with.

In what was recorded as the first national survey of Sri Lanka’s wild elephants (2011), it was revealed that there were 5,879 wild elephants. They included 122 tuskers and 1,107 calves.