Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Saturday, 25 August 2018 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

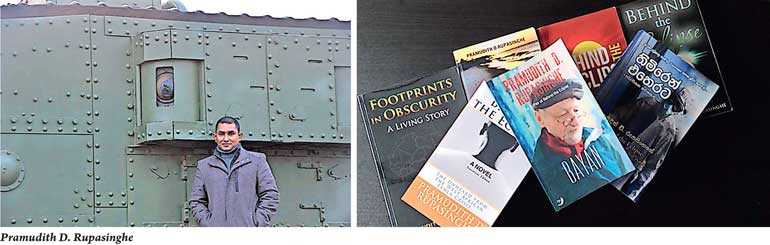

Author of ‘Behind the Eclipse’ and several other novels, Pramudith D. Rupasinghe is a clinical psychologist by profession and has worked in different parts of the world as a humanitarian diplomat. In the backdrop of the recent re-launch of ‘Bayan,’ his mellow work of 20th century literature set in Ukraine after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, he shares insights into the novel’s background and meaning in this interview

By Chandrika Gadiewasam

Q: Who is this amazing old man Ivan, did he really exist?

A: He does exist, and thousands like him in all ex-Soviet republics. Ivan is just one individual who encountered the abrupt, catastrophic shift of life, with the fall of Soviet Union. He is one among millions of people who lived a half of their life in the Soviet system, working in a communist working environment, especially in time of collectivism, trying to remain contented within the life granted to them.

In his nostalgic thoughts, constantly swinging between love and resentment – you may find those throughout the book – we see how exactly the life of the ordinary man in the USSR was. It also takes the reader on a virtual journey across socioeconomic aspects of the Soviet Union; especially about the class differences that were said to be non-existent, the paradox of communism. In conclusion, Ivan Nikolaevich is not merely an individual, but a semi-fictional character, a symbol of a segment of the current society of ex-Soviet republics.

Q: Ivan pines for old Russia; do you in a way share his nostalgia? How difficult was it to take the Sri Lankan out of you and write about a completely different culture? Despite the vast distance and differences, what are the similarities you note between the two cultures if any?

A: I think you pressed the right nerve. Some time ago, in one of the book reviews, another newspaper called me ‘a writer without borders’. What inspires me is immense diversity on this little planet Earth, especially cultures, people, nations, etc. I have a keen interest in cultures especially and oftentimes study them thoroughly. When I start writing a book I am always conscious of that my work is filtered through the mores, norms and customs of the context, by trying to live the life of the characters of my book. It is a living experience. Breathing in a story and its characters.

I believe that is vital to deal with author bias appropriately. I guess as a psychologist who has worked in different parts of the world, I am highly sensitive to diversity and that facilitates me in understanding the other cultures from within as it were.

I think when it comes to similarities and cultural differences between Ukraine and Sri Lanka, there are more differences than similarities. However, as anywhere else, a very simple lifestyle exists in the remote villages which is pretty similar to the lifestyle we used to have in villages, before the disastrous shift to materialistic lifestyle in Sri Lanka. I think Ivan represents all of that.

Q: You are a busy senior diplomat. How did you find the time and peace to write ‘Bayan’? Tell us more about yourself?

A: I have been working as a Humanitarian Diplomat for over 15 years, working in many different parts of the world. I would rather love to talk about the books and their subject matter rather than about myself.

Actually, finding time for writing is not that difficult though my life is full of unexpected travelling. I think there are two things. One, writing is my main coping strategy with work stress; I just vent it all out. Secondly, I usually write when I am on missions, and today I tend to choose my duty station based on its importance for my writing.

For example, for writing my forthcoming book ‘Rain of Fire’ I choose to work in all geographical locations where Rohingya communities lived (in Myanmar, Bangladesh, Malaysia and Thailand); for ‘Behind the Eclipse,’ I extended my mission in Liberia till the end of Ebola crisis; for termites, I went to Bangladesh, to the epicentre where the story takes place, so is ‘Bayan’.

I usually leave my office exactly at five, and by 7 p.m., after dinner I write for two to three hours every day. On weekends, I chose a hiding spot in a silent cafe and spend most of the time writing. While travelling, long layover times and long flights allow me to write. I do still remember I wrote half of ‘Bayan’ when I was in Ukraine, and the other half in Myanmar.

Whenever I come to Sri Lanka on vacations, I do not write; you tend to become busier than when at work!

Q: What final message or lesson do you wish your reader to take away from ‘Bayan’?

Q: What final message or lesson do you wish your reader to take away from ‘Bayan’?

A: It’s a psychological exploration of oneself. In one sentence that is it. ‘Bayan’ is a stimulation to its reader to discover the undiscovered of him or her as the story reveals the unconditional companionship Ivan develops with his Bayan – this inanimate object – as he grows older when everyone quits reachable radius of his life.

It is very common among aging people to develop such relationships with inanimate objects, it could be an old piece of clothing or anything as such. I leave this for the reader to discover, otherwise I will end up explaining every bit of underlying elements of the story which is very subjective. I have left an immense space for reflection for the reader to absorb the final message based on one’s experiences and background.

Q: ‘Bayan’ celebrates the environment, and you have described in loving detail the seasons, the forests, birds, fish and nature; is that intentional or merely in passing?

A: What helps Ivan to cope with the daily challenges of his age? From where does he find strength and boost his inner resources? It is through nature. The story is set with the most possible proximity to nature for that reason. Besides that, the seasons and the changes of landscape are used symbolically for highlighting transitions of different sorts in the story.

Q: This is a story about Ivan, so why is it titled ‘Bayan’? Or is it really a story about the Bayan? Why is this Bayan so special?

A: This story of millions of Ivans out there in ex-Soviet countries. Bayan, though is not heard in this part of the world, is a Russian accordion with round rough metal buttons that need to be pushed with effort unlike modern accordions , and in the book, it symbolises old Soviet life. Ivan has developed an inexplicable kind of companionship with the Bayan, which itself represents his nostalgia of his life in a Soviet Union that once existed. It is so special, as it says all.

Q: Tell us more about the actual publication, in terms of copies, reprints, translations, distribution and where we can get a copy?

A: ‘Bayan’ is currently available in online book retailers and stores around the world, and the international edition costs around $12. This time, unlike in usual cases where the translations are released a while after the book in original language is released, Sinhala, French and Spanish translations will be released in August. Russian, Ukrainian, Polish, Burmese and Bengali translations will be out in late 2019.

The good news for the Sri Lankan readers is a low cost print of ‘Bayan’ will be released in Sri Lanka by Minsara Publishers in August; it will be released with the launch of Sinhala translation of Bayan ‘Sisira Geethaya’ (translated by Rohana Kaluarachchi) and will be available in book retailers across the island.

Q: Are there any new projects you are working on?

A: Yes, ‘Rain of Fire,’ a story of a Rohingya Muslim boy who survived a boat wreck in the Andaman Sea while fleeing persecution in the land where he was born. In this story I make an attempt to look at the migration through a very human lens. It may be in the hands of my readers by end of 2019.