Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Friday, 11 October 2019 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

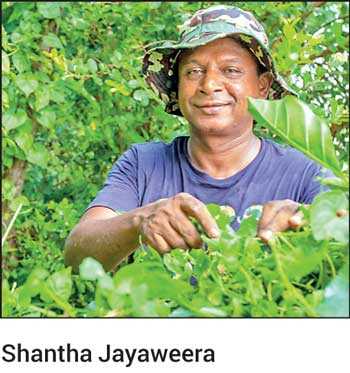

Shantha Jayaweera was a child when he first visited Colombo’s wetlands. Abutting the crowded city, the marsh was wild, untamed and brimming with life.

Shantha Jayaweera was a child when he first visited Colombo’s wetlands. Abutting the crowded city, the marsh was wild, untamed and brimming with life.

“It felt like this was a hidden place,” Shantha says, remembering that on that trip he saw birds skimming the water, and dragonflies in the reeds. He would learn that these lands were home to so many different species of animals and insects, including fishing cats, porcupines, otters and snakes.

Shantha’s love affair with the marshes would only grow stronger. Now 52 years old, he has spent decades working as a naturalist and wildlife artist and is the President of the Organization for Aquatic Resources Management.

Today, Shantha is on site at the Heen-Ela marsh. Tucked into a corner of Rajagiriya town in the Sri Jayawardenapura Divisional Secretariat area, the marsh is a part of Colombo’s wetlands. At present, it extends over 107 acres and encompasses three islands.

Shantha navigates these waters on a small boat, using a long oar to propel it through the water. Depending on what his task is for the day, he will carry saplings for planting or clay pots that he will bury in the ground to serve as a refuge for snakes in the rainy season.

Shantha knows this place like the back of his hand and what he sees concerns him. As he rows, he points to the banks piled with plastic bottles and bags, rubber slippers and bottles of every description. There’s more floating in the water.

All along the boundaries, small homes edge in on the marshes – and some of them dump more waste into the once pristine waters. In order to prevent further encroachment, the Sri Lanka Land Reclamation and Development Corporation (SLLRDC) has excavated a canal from two sides, creating a kind of buffer zone for the marsh.

Not all invaders come in on two legs

However, not all invaders come in on two legs. Shantha says invasive species are rampant across the area. In the water, you’ll also find exotic fish species – the result of people emptying their fish tanks into the canal and lake.

On land, about 55 to 60% is covered with overgrown grass, shrubs and herbs. Included among these are the tropical fruit trees known as wel-atta (Annona glabra), which were first introduced as a grafting stock for custard apples and then spread into wetlands around Colombo. In 2002, these trees covered some 60% of marshland, says Shantha. Now, they’ve swallowed up 85%.

And it’s not just the land. Covering the surface of the water like a carpet is the deceptively beautiful water hyacinth. Known to locals as ‘Japan jabara’, the free-floating aquatic plant has obstructed large parts of this marshland, preventing Shantha from accessing key routes on his catamaran. Spreading like a thick mat across the water, the plant competes with other aquatic species for light, nutrients and oxygen, and can even exacerbate flooding.

For Shantha, this is a huge concern. “What is really important is for the mud layer to stay accessible,” he says, explaining that the many birds and animals that call this place home, need this layer to survive.

In fact, a 2003 study identified 86 birds of which 35 species were aquatic. There were also sightings of several other important flagship aquatic species in this marsh including the fishing cat, the otter and estuarine crocodile, all of which are endangered. The conservationist adds that some of these species are so well adapted to the marsh, that they could not survive anywhere else.

Supported by the United Nations Development Programme – GEF funded Small Grants Programme, Shantha is responding to these challenges on multiple levels.

Supported by the United Nations Development Programme – GEF funded Small Grants Programme, Shantha is responding to these challenges on multiple levels.

First, he is trying to introduce indigenous marshland plants such as Kaduru (cerbera odollam) back into this ecosystem. He has also been constructing cement dens to serve as havens for different species of mammals and reptiles, notably these include bat houses Fruit Bats (Pteropodidae) and Micro-bats (Microchiroptera) that are key to controlling mosquitoes in this area.

“They are actually better at doing this than fish and dragonflies,” says Shantha. Finally, Shantha is working with communities around the wetlands to help him preserve them.

The aim of United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) – Global Environment Facility (GEF) Small Grants Programme in Sri Lanka is to support the achievement of global environmental benefits and the protection through community and local solutions that work in harmony with local, national and global action. The $ 2.5 million, four-year project extends up until December 2020.

Wetlands: A critical resource to the city

Having seen some early successes under the program, Shantha is in the process of rehabilitating some 60 hectares of degraded wetlands at Heen-Ela, and his refuges for snakes have helped prevent animal-human conflict across another 100 hectares. The project is also training youth from the neighbouring to identify and safely capture even venomous reptiles like the cobra and Russell’s viper, which can then be handed over to the Wildlife Department.

As part of his awareness-raising campaigns, he points out that the wetlands are a critical resource for the city. Thanks to them, water is purified as particles are filtered out, flooding is reduced and the city’s air pollution is curtailed. The wetlands even act as natural cooling systems, reducing the temperature in their surrounds. Beyond all this, Shantha wants those living in this area to recognise specific benefits they can enjoy.

Kan-kung grows wild all over the islands, one of the few traces of the farms that used to exist on these lands before 1977. There are many such edible plants and fruit here. For Shantha these can, and should be, resources for locals. “It is a good thing when people use the marshlands as a source of medicinal herbs, reeds for handicrafts and freshwater fish,” he says.

Shantha plans to work with the Government to conduct lectures for interested students who visit the marshland and offer vocational training to selected youth and women in the area, who could then create ornaments from invasive trees found in the marshland.

The future of our city

He is also very keen on promoting eco-tourism which would create livelihoods for families here and deepen their ties to the land. Through UNDP GEF support, he is now laying out plans to create boat tours and animal safaris that could help the city generate revenue.

Taken together, he hopes these measures will encourage locals to protect the wetlands. “Most capital cities don’t have such beautiful natural environments just a short walk away,” he says, “We must protect our wetlands, they are the future of our city.”