Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Friday, 30 October 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The outbreak in Bandaranayake Mawatha, Colombo is an excellent example of how diseases spread in underserved settlements in urban areas. The cluster consisted of small living spaces, home to around 62 families on a 20 perch land – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

By Chathurga Karunanayake

Urbanisation has intensified many of the most pressing global challenges over the last few decades. Today, responding to the COVID-19 pandemic has become top priority for the vast majority of towns and cities across the world, which account for over 95% of total reported COVID-19 cases according to the UN-Habitat COVID-19 Response Plan.

Urbanisation has intensified many of the most pressing global challenges over the last few decades. Today, responding to the COVID-19 pandemic has become top priority for the vast majority of towns and cities across the world, which account for over 95% of total reported COVID-19 cases according to the UN-Habitat COVID-19 Response Plan.

Research also shows that densely populated areas and underserved settlements without access to basic infrastructure facilities, those in strategic locations with high land value, those on reservations required for new infrastructure and those on the periphery with adequate housing requiring only improvement of infrastructure continue to provide a ready channel for the resurgence of pandemics.

Sri Lanka is no exception to these realities. Densely populated and underserved areas, including slums and shanties, have seen the incidence of a high number of COVID-19 positive cases during the past few months. Given that well-developed urban areas generally react fast in terms of mitigation efforts, the hardest hit during pandemics are those in less developed areas. They are also vulnerable to such outbreaks highlighting the urgency with which solutions to these issues need attention.

As the world responds to the COVID-19 pandemic and works towards recovery, Sri Lanka should explore ways of halting the spread of future pandemics, stimulating recovery, and building resilience in underprivileged urban settings. This blog discusses how Sri Lanka can address these challenges.

COVID-19: Impact in urban settings

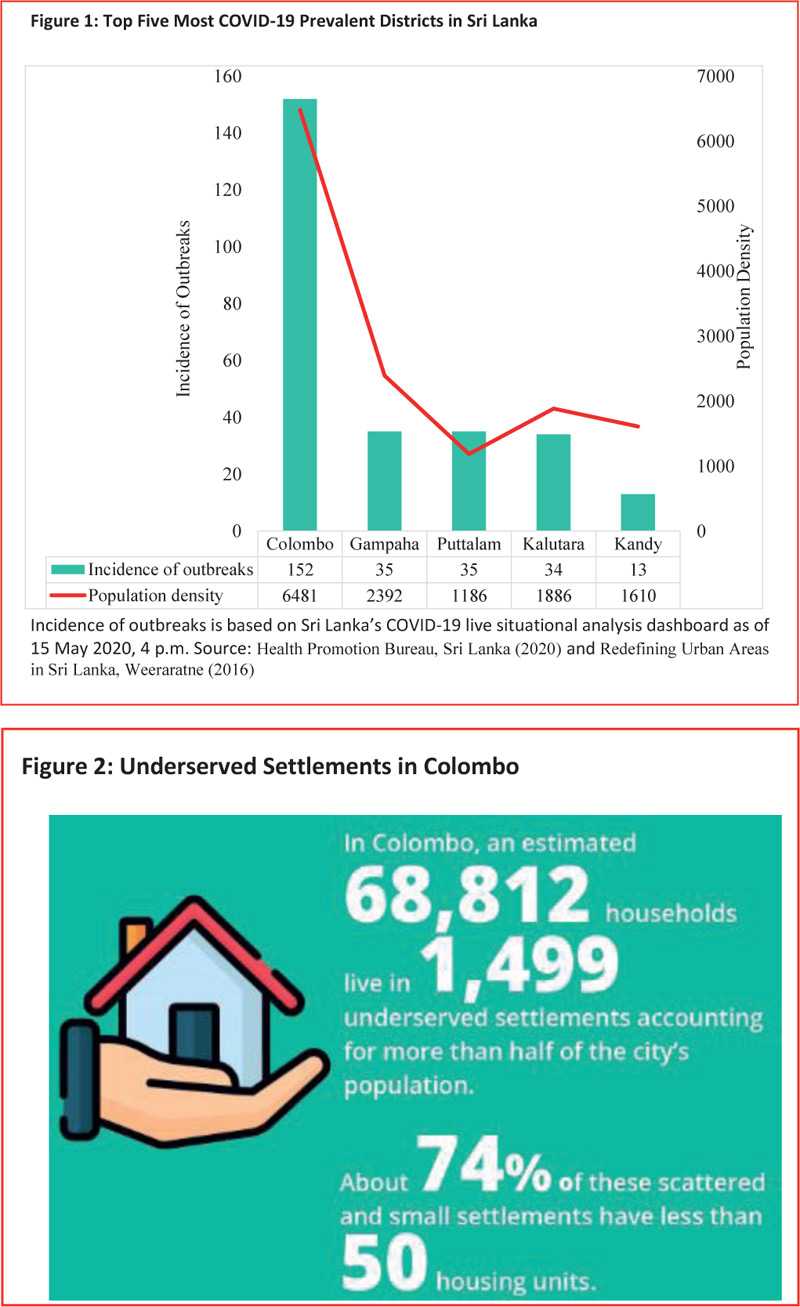

Despite lack of exposure to similar pandemics in the past, Sri Lanka was exemplary in curtailing the first wave of the COVID-19 crisis. Early measures adopted by the country, such as self-isolation, contact tracing, referring suspected cases to quarantine centres, curfews, lockdowns, and closure of schools and workplaces made this possible. However, the numbers (Figure 1) could have been further controlled had there been proper urban planning procedures. This is especially so, given that some large clusters were located in small urbanised areas in Colombo.

The outbreak in Bandaranayake Mawatha, Colombo is an excellent example of how diseases spread in underserved settlements in urban areas. The cluster consisted of small living spaces, home to around 62 families on a 20 perch land. Not only do these small housing units lack basic amenities such as sanitation, water, and ventilation, but their placement also makes social distancing an impossible task. In such neighbourhoods, residents tend to congregate in public spaces and visit neighbours. Tracking and controlling socialising patterns in highly congested areas adds to the challenges making lockdowns and curfews redundant.

According to the 2016 Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES), urban areas are home to a majority of families living in shanties and slums. Nevertheless, the current administrative definition of ‘urban’ significantly underestimates the real extent of urbanisation in Sri Lanka. According to UN-Habitat III, in Colombo, an estimated 68,812 households are located in 1,499 underserved settlements accounting for more than half of the city’s population; about 74% of these scattered and small settlements have less than 50 housing units (Figure 2).

Furthermore, a majority of slum dwellers in urban areas are employed in self-managed, low wage jobs in the informal sector, earning daily wages. The informal nature of their employment, with no protective measures, makes them vulnerable to sudden earning losses, access to food and other basic needs. This in turn exposes them to higher risks, when they are compelled to ignore precautionary measures in desperate attempts for survival.

Initiatives to improve underserved settlements

In the recent past, successive governments have undertaken many initiatives to improve the conditions of slums, shanties, and other underserved settlements in urban areas. After the war, the Urban Development Authority (UDA) embarked on a project to rehouse underserved settlements as part of the Colombo City Beautification project.

Several regulatory reforms have also been implemented: (1) a policy decision to relocate 66,000 low-income people from underserved settlements into high-rise housing in 2010; (2) a national housing programme named ‘Janasevana’ aimed at building one million houses during 2010-2015; and (3) the ongoing Colombo Urban Regeneration Project to construct 30,000 low-cost housing units within the next three years, and another 40,000 units in the three years thereafter.

However, much more remains to be done – particularly in terms of urban planning and management – as exposed by COVID-19. The pandemic has allowed room to re-think, re-plan, and re-design urban settings to be more resilient to future outbreaks.

Building better

Building resilience and ensuring preparedness is a worthwhile investment compared to costs that have to be incurred when managing an emergency unprepared.

In this regard, addressing shortcomings in urban public healthcare facilities is important. As recommended in IPS’ Sri Lanka State of the Economy 2020 report, rectifying long standing and often neglected issues that weaken healthcare systems such as expanding designated hospitals for infectious diseases, investing in intensive care units, expanding testing capacities in hospitals and incorporating enhanced channels for informing and educating the under-privileged communities are some key measures to strengthen the health policy response.

In terms of assisting livelihoods of the underprivileged, it is important to promote economic inclusion. While the provision of funds and food rations at a subsidised rate is beneficial, it is important that more emphasis is given to permanent solutions. In doing so, as suggested by The World Bank, slum upgrading can include aspects such as improving marketplaces and kiosks for street vendors and supporting local employment opportunities through labour-intensive works.

Living conditions of slum dwellings need improvements coupled with relocation activities. This requires proper urban planning to manage Sri Lanka’s dense population and enforcement of policies to ensure a successful relocation exercise, not only in urban centres but also in peri-urban areas and suburbs. Urban planning should focus on informal settlements and the urban poor that have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic. As a solution to high dense populations living in small areas, a threshold level of population density per square mile can be adopted, based on extensive research.

Disaster-risk-reduction planning and response and pandemic prevention planning must be incorporated into urban planning in Sri Lanka. As suggested by Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), this can include measures such as establishing an emergency operations center, continually assessing needs, identifying resources, planning for response, implementing the response, and preparing communities for recovery.

(This blog is based on IPS’ ‘Sri-Lanka: State of the Economy 2020’ report on ‘Pandemics and Disruptions: Reviving Sri Lanka’s Economy COVID-19 and Beyond’.)

[Chathurga Karunanayake is a Research Assistant at IPS and holds a BA in Economics (Honors) from the University of Colombo. She also holds a DipLCM from the University of West London, UK. (Talk to Chathurga – [email protected]).]