Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Monday, 27 July 2020 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

It is estimated that roughly 10-15 million people live in these areas of prime elephant habitat. Much of this overlaps with agricultural land, as the majority of rural Sri Lankans identify themselves as farmers, and so the foundation is laid for the tragedy that is the Human-Elephant Conflict

“They show us what’s missing in our lives, and how to love ourselves more completely and unconditionally. They connect us back to who we are, and to the purpose of why we’re here” – Trisha McCagh

What is Human-Elephant Conflict?

The Sri Lankan elephant (Elephas maximus maximus) is one of three recognised subspecies of the Asian elephant (the others being the Indian, Sumatran and Borneo elephants), and are native to the island of Sri Lanka.

Much like the elephants of Africa, Sri Lankan elephants form matriarchal herds of more than a dozen individuals. Elephant calves are known to live with their mothers for up to 15 years, after which males disperse and females continue living with the herd.

Have you ever wondered why you love watching them in the wild? Well the above quote might shed some light. The fact of the matter is almost all of us love them. We find them fascinating, wonderful, and majestic. We use so many words to describe the feelings they spark within us, but do we do enough to help protect them?

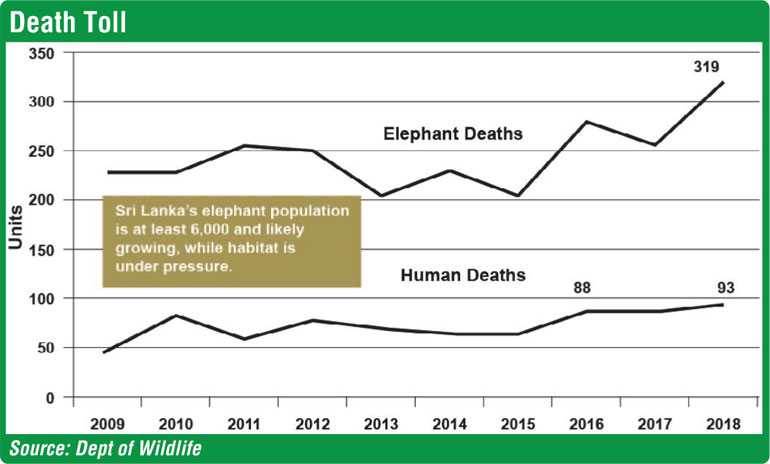

Perhaps you already know that in 2019, as per official figures, out of Sri Lanka’s remaining wild elephant populations, 405 died, a very large majority of them killed by humans. Sadly, the greatest threat to elephants in Sri Lanka today is the ‘Human-Elephant Conflict’ (HEC) which used to claim, on average, 200 or more elephants each year.

For the first time, elephant deaths exceeded 300 in 2018, and now 400 in 2019 – an exponential increase of 100 elephants year on year. Which begs the question – just how much more time do they have left?

Ultimately, that decision is up to us, as a society and as a country, if we want these majestic creatures to share a future with us, on this same island. We are, after all, at the very top of the food chain and what we say goes!

Do we want Sri Lanka’s elephants to join the statistics as being yet another species that fell victim to the Anthropocene era? Or do we want our children and their children and the generations to come, to enjoy the same thrill and wonder that we do when we set eyes on dozens of elephants walk out, at dusk, towards the mighty Minneriya Wewa during ‘The Gathering’? Well, if the answer to that question is ‘yes’, then we must take action… and we must take action now before it is all too late.

HEC explained

In Sri Lanka, for many thousands of years, elephants have lived in harmony with humans. The beginning of the end for them probably began at the time of British rule, when they were shot by the thousands, for sport and for their ivory, and their habitat in the central hills taken over by tea and coffee plantations.

The dry zone, however, was sparsely populated during the British era but successive governments, from the 1950s onwards, started large scale irrigation schemes and resettled people from the wet zone and other parts of the dry zone and opened out forest land for agriculture. This was really the start of HEC (as we know it) in Sri Lanka. These people simply did not know how to coexist with elephants as they were not used to living amongst elephants.

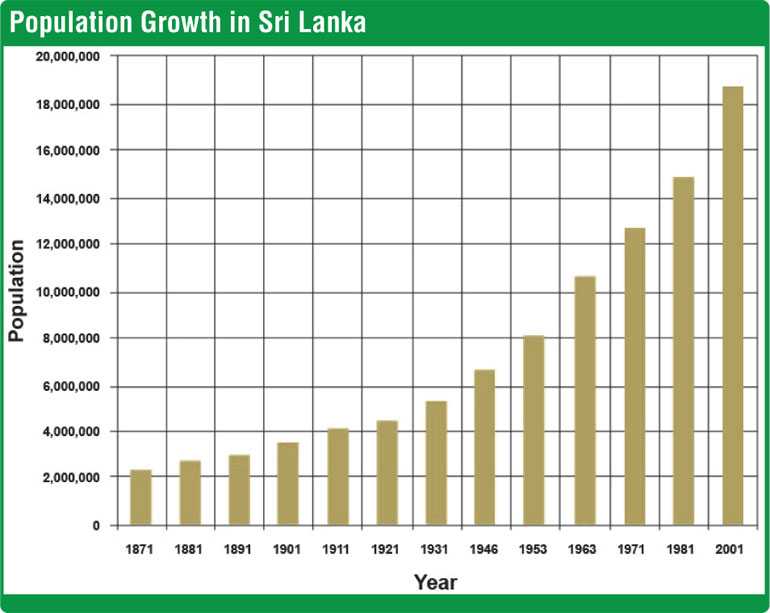

With a land area of roughly 4.5 million hectares, Sri Lanka is a small island, however, the population of its human inhabitants has exploded, especially since the 90s, to approximately 23 million today. Humans share roughly 44% of the island’s landscape with elephants – 2.8 million hectares – largely restricted to the dry zone in the north, north central, east and southeast of the country.

It is estimated that roughly 10-15 million people live in these areas of prime elephant habitat. Much of this overlaps with agricultural land, as the majority of rural Sri Lankans identify themselves as farmers, and so the foundation is laid for the tragedy that is the HEC.

Cruel ways to die

200 or more elephants are killed each year in Sri Lanka in unimaginable and cruel ways.

On average 70 humans, too, fall victim to the HEC each year. This number, too, has increased exponentially in the last two years, to 85 in 2018, and over 100 in 2019.

Why does HEC make the headlines?

These are the average human fatalities in a year attributable to animals/insects (based on 2018 figures): Snake bites – 483, Dengue – 421, Murder (Human on human) – 358, Rats – 89, Domestic animals (Rabies) – 12.

The number of human deaths per year due to road accidents is 3,000, Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs – heart diseases, cancers, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, strokes, etc.) deaths top the list at ~ 140, 000 – 75% of total deaths in Sri Lanka are caused by NCDs – diseases which are caused by lifestyle choices and are largely avoidable (directly caused by tobacco use, harmful use of alcohol, unhealthy diet, and physical inactivity).

It is said that one in every five people in Sri Lanka will die of a NCD. But when was the last time you saw these headlines make the news?

Quite simply elephants are big, they are visible, they will fight back when provoked but they cannot vote!

HEC is the biggest threat to elephants in Sri Lanka today. Therefore, it is the biggest issue that needs to be solved for the conservation of Sri Lanka’s wild elephants.

(This is Part 1 in a three part series on the Human-Elephant Conflict.)

(FEO is a non‐political, non-partisan organisation that provides a platform for connecting interest groups with a patriotic interest in safeguarding Sri Lanka’s natural heritage through conservation and advocacy. www.feosrilanka.org)